San Diego has finished pulling more than 155,000 pounds of debris out of just one prominent riverbed encampment, illustrating how complex and expensive responding to homelessness can be when it’s allowed to last for years.

The operation required a multimillion-dollar state grant and some of that money will now be spent helping former residents get, and keep, housing.

Around 100 people had lived at the site by the San Diego River.

“The intended goal is saving lives,” Ketra Carter, a leader of the city’s homelessness strategies and solutions department, said in a phone interview.

Officials are now pivoting to other parts of the river ahead of a rainy season that threatens to wash trash, and people, out to the ocean.

Homelessness has grown countywide every month for two-and-a-half years, and the number of riverbed encampments increased after San Diego passed its camping ban. A recent census by the San Diego River Park Foundation found more than 420 people living by local waterways, the nonprofit’s highest tally yet.

Many officials have said the region needs to invest more in prevention, and some philanthropists and nonprofits have increasingly turned toward rental assistance. But while the city and county do offer aid to residents facing eviction, demand has long dwarfed supply.

San Diego council members are in the early stages of forming next year’s budget.

The recently cleared riverbed encampment was beneath Interstate 5 near Sea World Drive. Dubbed “The Island,” it actually consisted of several islands that grow and shrink with the changing tides. The area had featured multiple shacks built out of wood and tarps. At least one was two stories tall, officials said.

Leaders don’t yet have a breakdown for where every one of the encampment’s 96 residents went. But while a few effectively disappeared, Carter said most accepted some form of shelter, including sober living, hotel rooms or tents at one of San Diego’s designated camping areas by Balboa Park.

Carter was unaware of any arrests.

Outreach workers began visiting the site in July. The nonprofits People Assisting the Homeless, or PATH, and Healthcare in Action were supported by $17 million from California’s Encampment Resolution Funding Program, a grant that’s being split by multiple agencies around the region.

It’s hard to say exactly how much has been spent just on The Island, although the answer could easily be in the hundreds of thousands. The encampment residents who accepted offers for help can continue to draw from that pot until June 2026 for needs ranging from apartment deposits to job preparation, and the National Alliance on Mental Illness is helping oversee the latter effort.

Yet the city of San Diego had to spend its own money on the cleanup itself.

On Thursday, dozens of city staffers and first responders marched through the muck. Some raked up broken glass. Two men wrestled with a tree trunk wrapped in trash bags. Deep water surrounded much of the area, so someone had placed sheets of wood on top of a chain link fence and balanced both on blocks of plastic foam, creating a makeshift barge that could pull piles of debris from shore to shore.

Skid loaders crisscrossed the nearby sand. One balanced chunks of concrete in its metal bucket, and a reporter remarked that encampment residents had surely not been the ones to pour that cement.

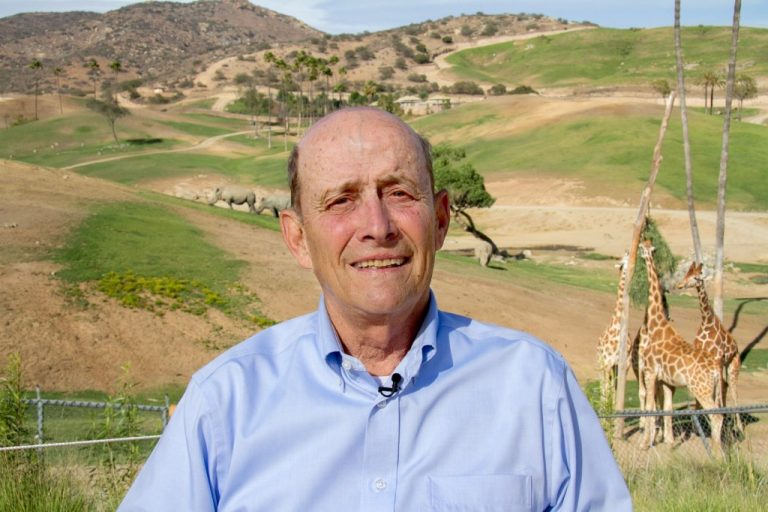

“You’d be surprised,” said Franklin Coopersmith, the city’s deputy director of environmental services. Then he pulled up a photo of one structure that had its own fireplace.

Coopersmith said most of the big stuff was gone, especially after a crane earlier in the week had dragged out boats, generators and parts of a motorcycle.

Trash crashed into dumpsters. The sand slowly cleared.

Later in the morning, a bearded man appeared downriver. He stood on an inflatable raft with a kayak paddle, and sunlight flashed off the water every time he took a stroke.

A woman in a reflector vest watched from the sidewalk. “That’s the boat he stole from us yesterday,” she said quietly.

A nearby police officer cupped two hands to his mouth. “You want shelter?” he shouted.

“I live in La Jolla,” the man said from the boat. “I got a place.” He kept paddling.