By Gwendolyn Bounds

For The Washington Post

Eight years ago this month, like many Americans, I made a resolution to become fit and strong.

About 7 in 10 U.S. adults set goals at the start of a new year, and personal health or fitness goals are the most common, according to Gallup. But by mid-February, 80 percent of the people who set New Year’s resolutions will have abandoned them, Gallup reported.

I, too, had tried before, my pledge generally lasting a few months before old habits (sitting! screens!) returned.

But that year was different. I had a specific goal in mind — to compete in one obstacle course race. Tying my New Year’s resolution to something concrete was a critical first step to exercise being almost a nonnegotiable in my day. Last year, I completed my 56th race.

Once a resolution is made, specific tactics make it more likely to stick. Here is what habit and fitness experts, and my own experience, suggest:

Have a longer-term obtainable goal

Going out too hard is a common misstep, said Peter Duggan, a strength, conditioning and rehabilitation specialist at Fuel Sport & Spine in New York. “People say ‘I’m going to go crazy’ and then come in to see us injured by the middle to end of January,” he said.

Having a longer-term goal and plan is better, suggested Duggan, who works with professional athletes and amateur fitness enthusiasts. That can be as simple as a 5K race in April or a 90-day first-quarter (Q1) challenge where you measure your January progress against your February progress and your March progress against February and January.

This way, you have some form of momentum. But if January blows up because you get sick, then you still have February and March, Duggan advised. Start small if you’re a newcomer: Go from walking or jogging in January a couple of times a week to running 25 minutes two or three times a week in February and longer in March. Then set another goal for the next quarter.

“You can’t just run up Mount Everest,” Duggan said. “You have to start at base camp. Use January or Q1 as base camp.”

Time block and preprogram your workout

Waking up and thinking, “I’m going to exercise at some point today,” is a vulnerable strategy. You must then spend extra time figuring out what you’ll do, when you’ll do it and where — time you probably don’t have in an already full day.

Instead, schedule and block out your exercise moments for the week, in advance, to reduce the likelihood of slipping back into old habits — such as coming home, jumping on the couch and scrolling on the phone.

“Physical activity takes time, and you need to be mindful of your other habits that need to change,” said Chad Stecher, a behavioral health economist and an assistant professor at Arizona State University. “Not only are you building a new habit, but how does that habit fit into the rest of the day?”

My solution: Since I live by my digital calendar for work, each week’s exercise gets scheduled in the same color-coded blocks as my meetings. I don’t skip meetings, so I don’t skip my workout. This removes the barrier of “at some point today.”

Leave yourself visual prompts

Cues, particularly visual ones, are some of the strongest motivators to create a new habit, said Stecher, whose research focuses on habit formation.

For instance, placing your running shoes or workout clothes where they are the first items you see when you wake up reduces the likelihood exercise will slip your mind, Stecher said. It also serves as a commitment reminder that “you intended to do this,” he said.

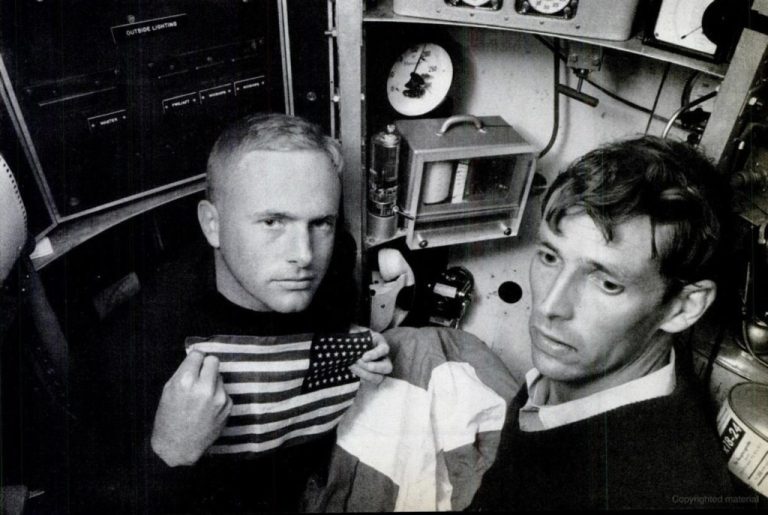

In my living room, I keep a nice box that holds a yoga mat, balance board and foam roller. Seeing that box each time I walk to the kitchen means I’m more likely to use what’s in it when I have five to 10 minutes to spare.

Accessibility also matters, Duggan said.

“It has to be convenient,” he said. “We all have weeks when we are overwhelmed, but you can still carve out 20 minutes in your living room with some dumbbells or a HIIT [high-intensity interval training] class on an app.”

Build accountability slowly

Recent research suggests the amount of movement we get in a day, as measured by a wrist tracker, is a stronger predictor of mortality than age, smoking or even diabetes.

There is no shortage of apps, fitness trackers and health devices to gather data on our movement. The key is not letting the devices get in the way of actually exercising – especially when we are first building a habit.

“I think if you are new to exercise, you don’t need all the fancy gear,” Duggan said. “Just start. Listen to your breath and feel your heart rate. As you get better, and crave more data, then you can buy more tools like a watch and a heart rate monitor.”

A less complex (and free) tracking tool is what I call “completion signaling” — the act of checking a box and recording your progress when exercise is done. For instance, when doing multiple sets of an exercise at home, I move a pile of machine screws or small rocks from one mug to another. And each time I complete a workout, I mark it as “Done” in my digital calendar.

Each action, however small, is a clear visual for me of forward movement and accountability. Put more simply, the reward of marking a workout as completed feels good; not checking that box feels bad. So, I am more likely to get the workout done.

Make exercise part of your identity

Exercise becomes truly nonnegotiable when it’s part of your core identity, Stecher said, noting a growing body of research linking identity to maintaining behavior change. “Then, when your routine is interrupted, and the normal cues aren’t there, you’ll still go to the gym,” Stecher said.

This rings true. Eight years ago, “fit person” or “athlete” were nowhere among the descriptors my friends and family used for me — nor ones I used for myself. Now, those monikers are as core to my sense of self as “writer,” “spouse” or “daughter.” The tactics above made that possible.