How do you deal with the ballooning cost of medical care? The answer for a growing number of Americans: Pay it with plastic.

Medical credit cards, once limited to esoteric procedures that weren’t covered by insurance, have grown in popularity in the past decade as health care costs have continued to rise and Americans are spending more out-of-pocket for even routine procedures.

But these products can cause trouble for patients, with many of them overpaying for specialized medical finance products, signing up for contracts they don’t understand or, in the worst-case scenario, piling on debt they can’t get out of, according to a recent report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

“These new forms of medical debt can create financial ruin for individuals who get sick,” CFPB Director Rohit Chopra said in a statement.

More middlemen

Millions of patients are using this type of financing. CareCredit, a subsidiary of Synchrony Financial and one of three major medical cards examined in the report, has 11.7 million cardholders this year, triple the number a decade ago, the CFPB found.

Medical credit cards or installment loan companies pitch their services to doctors promising to save them time and money. Hospitals are drawn to these types of plans because they get paid upfront by banks for their services, Crain’s Chicago reported last September.

“Lenders, for their part, see an opportunity to capitalize on the growing gap between the cost of medical care and what many Americans can afford,” the outlet wrote.

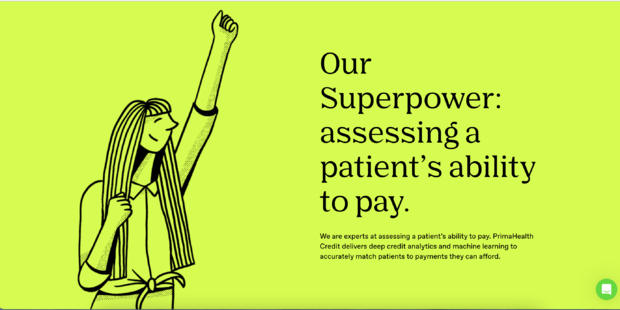

PrimaHealth Credit, one loan provider highlighted by the CFPB, promises on its website to “generate up to 20% more revenue” for medical providers. “We take care of payment processing, resolve past due accounts and handle all credit reporting, so you don’t have to,” the company claims.

PrimaHealth founder and CEO Brendon Kensel said most patients use this financing for dental and orthodontic work, while the company also offers financing for procedures like outpatient surgery, LASIK, cosmetic surgery and hair replacement services. The APR for this loan can rise to 24.99% for someone with a low credit score, according to the site.

Screenshot

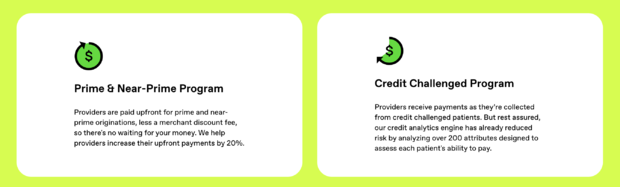

PrimaHealth has two classes of patients, according to its website and the CFPB. For people with good credit, PrimaHealth pays the medical provider upfront, minus a fee. But for patients with worse credit, the provider receives payment only as the patient pays off their bill.

Because “the provider carries the risk of the patient not paying their full bill,” the CFPB writes, being signed up with PrimaHealth could lead providers to avoid patients they see as a credit risk, such as “people with limited English proficiency, older Americans, and people with lower incomes,” the agency writes.

Screenshot

Kensel took issue with the CFPB’s analysis, saying the service extends access to those who can’t pay for care upfront. “The high cost of health care is really the crisis in the U.S.,” he told CBS MoneyWatch. “Historically, only people with good credit get approved for finance. In my view, unequal access to finance leads to inequality.”

Kensel, who ran an orthodontics practice before starting PrimaHealth, blamed inadequate health insurance coverage for the cost crisis. Asked whether doctors should consider lowering their fees, Kensel demurred, saying that most medical costs were “predictable” but that health plans often skimped on dental and orthodontic work, which is often considered “elective.”

“Most people don’t have an extra $5,000 lying around, and being able to access a monthly payment plan is the difference between being able to access care for their kids and not,” he said.

Poor decisions

The CFPB questions whether specialized medical financing truly expands access to the underinsured. Instead, the bureau writes, formal financial services like medical credit cards or installment plans have come to replace informal, often zero-interest payment plans offered directly by health care providers.

That added convenience for doctors can come at a high cost to patients. Patients, who are often pitched these financial products in the midst of trying to make medical decisions, often miss crucial financial details like the interest rate on a loan or its specific payment terms, the CFPB found. And doctors aren’t penalized if they suggest a less-than-ideal financial product because they’re not bound by the same laws that bankers are, as some legal experts have noted.

“The employees at medical offices are selling a product they know little about without fully disclosing the terms and conditions to their patients,” one patient complained to the CFPB.

Another patient described being signed up for a CareCredit card by their dental office, which pitched it as an interest-free payment plan costing less than $100 a month, only to be charged $1,400 in interest two years later. And one consumer told the CFPB their household was signed up for a credit card with no notification whatsoever.

“I am a senior citizen and went to a dentist office in my area to have them do a routine check up on my wife’s teeth. They only did two x rays, yet I received a bill for $14,000 for services she never received or we agreed for. The dentist office opened up a credit card in my name in order to pay for these services without my consent,” wrote the person, adding that they “do not speak good English.”

“I never received any receipts or copies of anything until I received a bill in the mail from the credit card company,” the person wrote, according to the CFPB.

$1 billion in interest payments

Patients using specialized medical cards wind up paying far more in interest than they would have in other circumstances — even paying with a general credit card. Many cards, for instance, offer an interest-free period, during which interest on a health procedure builds up but isn’t charged to the patient. If the person doesn’t pay off their entire debt during this time, they can be forced to pay a high amount of interest all at once.

“Our research suggests that many patients — specifically those who are unable to pay off a deferred interest product during the promotional period — can pay significantly more than they would otherwise pay,” the CFPB noted. “Interest rates for medical financing products are generally higher than the interest rates for other products, such as general purpose credit cards,” the report found.

In the three years between 2018 and 2020, people using medical cards or installment plans incurred $1 billion in deferred interest, the CFPB found.

Since medical finance offers are basically indiscriminate, according to the report, patients who find themselves on the receiving end of such a pitch should do their own research, the CFPB advised. For instance, they shouldn’t assume that a finance-ready medical procedure won’t be covered by insurance.

Hospital patients also should inquire about reduced costs through charity care — discounts for poor patients that nonprofit hospitals are required to offer as a condition of their tax-exempt status.