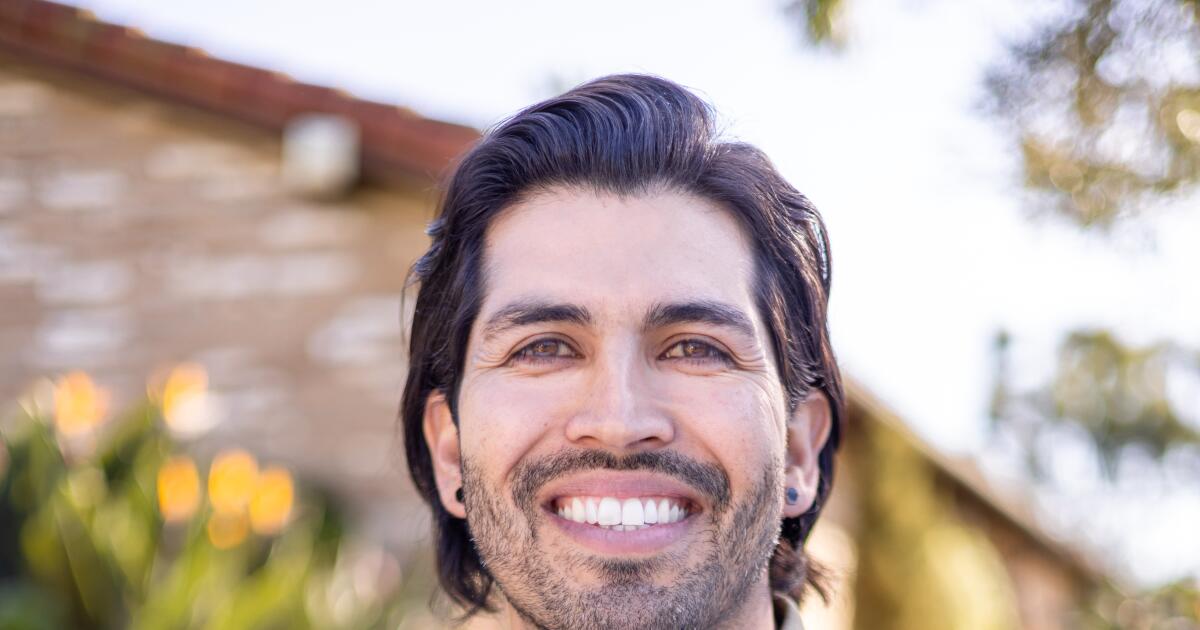

Even as a kid, it was always important to Juan A. Reynoso (whose Ipai-Kumeyaay name is “nemuuly”) to provide as much context and background as possible in order for him to be comfortable sharing his perspectives. He would eventually realize that it was part of his natural talent as a storyteller, communicator and bridge between different groups of people.

“I am a cultural storyteller and public speaker … weaving connections among communities that, maybe historically, don’t commune in the same spaces,” he says. “And finding commonality within our intersections, within our identities, our culture, our experiences.”

Reynoso, whose name “nemuuly” (neh-mool) means “grizzly bear,” is a Two-Spirit member of the San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians. He’s also a co-founder and co-executive director of The Queer Sol Collective, a nonprofit centering 2SLGBTQIA (Two-Spirit, LGBTQIA) leadership and voices in land and social activism, and a deaf and hard of hearing specialist for the Valley Center-Pauma Unified School District. He took some time to talk about his desire to help people connect through stories, his understanding of his Two-Spirit identity, and his framing of Thanksgiving through a lens of survival, resilience and gratitude. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity. )

Q: How did you first develop a personal mission of connecting people through storytelling?

A: Many, if not all, cultural groups have oration, or oral histories, oral stories that were around before written texts. In my family line, everyone in our community, there are different roles and capacities. Some people carry our songs, our bird songs; or they carry our dances; some people are natural teachers or spiritual healers, or community builders. I always found my life as a weaver, as a community person who brings connections to people, but through stories. In doing a lot of identity work, when I was able to listen to different people’s stories, it was very easy for me to find the similarities in people’s stories as an observer and also find myself in those stories. So, I just naturally started to grapple with bringing people together and saying, ‘OK, well, I can see how this looks this way and how you can see it that way, and how my story can also evolve or kind of move this story into a different direction.’ It was very natural and organic, coming into it as I got older. I’m 40, so through my life experience, there’s been a lot of grief, a lot of loss in our community. Particularly my family, and not to quantify or to dismiss anyone’s experiences, but things that most people should never have to go through or experience in their life, I would say that my family has gone through it. So, I think those experiences of loss and trauma and hurt and joy — at the end of it is always joy and grace and compassion — have really built this story for me and allowed me to look at people from a humanistic standpoint and say, ‘OK, I may not quite understand or agree with where you’re coming from, but I can see your story. I can see how my story can fit your story.’ It’s really just being more understanding of people and their perspective and their position. For me, storytelling has just been an evolution of my inherent gifts, just a natural calling, a natural teacher, natural oration.

I think for a lot of Indigenous people in my community, all of our history, most of our stories, they weren’t written down in textbooks. We are oral people. We have oral histories that exceed tens of thousands of years, and I think, as storytellers, we are historical preservationists. We hold those stories with a lot of deep-rooted intention, and I feel like it’s a passing of responsibility. In the standardized, Western view of communication where you have to be done in 10 minutes, 15 minutes, a very linear way of communicating, you miss the humanistic piece. You miss the opportunity for people to see themselves in your story, and vice versa.

Q: On your website, you identify as Two-Spirit. Can you help us understand what that means, in general? And, what it means for how you see and understand yourself?

A: “Two-Spirit” really is an umbrella term for people who can be and identify as non-binary, as trans, as bi, as gay, in any part of the LGBTQIA-plus community. Anyone who’s gender expansive, but particularly only used by Indigenous people. It’s a term that was created in the early ‘90s through a conference, an LGBTQIA kind of symposium with a bunch of Natives, and they decided to create a pan-Indigenous term, to create an identity that not only speaks to our genderqueerness and who we are in relationships or expressively, but really our cultural and our community responsibility. I think this is really where there’s a huge understanding and growing through what that means to be Two-Spirit. For a long time, I didn’t use [the term] at all. I really do love the terminology, the word “queer” because I feel like it was more expansive. Then, I would hear “Two-Spirit” and I was like, ‘Well, I don’t really know. What does that mean?’ I felt like it was kind of boxing me into this type of binary construct of male/female. The more I started to identify and look at what that meant, from a queer perspective and from an energetic perspective in my community, it’s about social responsibility and community of responsibility.

As Kumeyaay people, we have our own terminology that we use; we would say we are “ipai” and it means “the people.” “Ipai” is a northern Kumeyaay word, which means “people” and if you are down in San Diego’s south or east area, you’ll hear “tipai.” It sounds the same and it’s with a “T” versus an “I,” and means the same thing, it’s just a different dialect for northern and southern Kumeyaay. As queer people, we would say we’re “ipai hellyaa” (ee-pye shlah). In a modern context, I would say it means genderqueer, gender expansive. It’s anything that exists outside of the binary. When we look at language, it’s interesting because even our concepts, our Indigenous understanding of the world, our original practices don’t place them in these boxes. It’s very expansive. It’s more of, ‘You are beyond gender.’ For us, literally, “ipai hellyaa” means “person of the moon” because “hellyaa” is also our word for “moon.” Basically, “moon people” and when you think about the association of the moon in other cultures, it’s usually equated to emotion or energy field. When I heard that, I was like, ‘Oh, that makes sense. I am naturally a very emotional person. I hold a lot of emotion. I can show it, I can give it. I can absorb it.’

To answer the second part of your question of what it is to be and live as an “ipai hellyaa,” Two-Spirit person, sometimes it’s being more empathetic or more compassionate, which, in a modern social context is usually equated to being more feminine. “You’re so nurturing, you’re so motherly, or loving.” We love to put all these labels on what that means to be “soft” or “compassionate.” On the other side where there’s “logical” or “linear,” “structure,” “doer and provider,” all of these kinds of characteristics are what might be considered a masculine identity. When I think about how I’ve navigated the world, from a young child to now an adult, and still evolving, I’ve really seen how all of those intertwine and have worked in my life at all times, within every second of the day. It really feels like being a chameleon, being very fluid with monitoring and seeing the interaction I’m going to have with certain community members. Or, with the work presented in front of me, it’s being able to go into conversations and being able to read and become a space of safety that — whether it’s a feminine-presenting or a masculine-presenting space — is allowing myself to kind of be in all spaces at any time, depending on what I feel is necessary. That makes a lot of sense for me, seeing how those characteristics and those energies, the feminine and masculine and everything in between, really drive how I commune with people, and really drive how people see me and whether they are comfortable around me. For me, it’s about being a weaver and being a bridge amongst different community people, genders, and things that might not really see each other. Being in spaces where, maybe, I’m hearing my linear, logical, masculine brain saying something, and I can hear it and I can see the story. I understand what this person is trying to say and where they’re going. Then, I can take that information and listen to the counterpart, the more emotional, empathetic ‘All I need is this’ and really say, ‘Oh my gosh, you both should do this.’ You’re able to see yourself in both parties at all times, at any time, if that makes sense.

I feel like I identify as male. I would say I’m masculine-presenting, but I also think to myself, had I, at a younger age, not having been programmed to wear a certain thing or speak a certain way, would I be the way I am today? I think that would be a different story, I don’t know. We’re all products of our upbringing and I think that really informs how we are as adults.

I think it’s still evolving, my understanding of being ipai hellyaa, Two-Spirit. Now, more as community, has really moved into community responsibility and leaving legacy for the next generations. What can I literally, physically, tangibly leave for those to come to say, ‘Hey, you know what? I see myself in this story. I’m also in my tribal community’s oral stories’? Because we’ve always been there, but how do we remind people to bring them back up? How do we inform even our own communities to continue to share stories about gender-variant people? As ipai hellyaa people in our Kumeyaay community, when women, and this is hundreds of years ago, but when women would be within their cycle or their moon, they would all go together up into the hills, to the rocks, and be in community with one another. The men would stay behind and take care of the kids for several days. Ipai hellyaa people were able to move in and out of those positions, so if we wanted to go and be with the women, we would go there, or we would stay with the men. We, basically, were caretakers of both spaces. When I think about that, you are weaving. You are like a mediator amongst these genders because you understand both energies, and you are both energies at all times.

Q: This is the time of year when a lot of people are focused on the story of Thanksgiving — a myth, really, that imagines a largely benign interaction between the Wampanoag people and the early English settlers in 1621. Are you comfortable sharing the kind of story and connection you find yourself focused on during this time? And, what kind of responsibility and accountability would you like to see others, including the Union-Tribune, take in these and other stories that we tell, especially those that are shared about communities of color and other marginalized groups?

A: I think it’s important to recognize that my positionality, my rearing as a child, has informed my decision today, as an adult, to either practice the Thanksgiving, the harvest timeframe, or people have a right to completely dismiss it. I think it’s a very unique experience in Native country. We all experience and see this this time differently. I think, based on our experiences with it, that informs how we respond to it, or whether we participate in it. I heard this elder, about two years ago. They’d done a play about this time season, the harvest season, the Thanksgiving holiday. She basically used the terminology “survivor’s supper.” For me, it really stuck with me, and I thought, ‘“Survivor’s supper,” what an interesting way to look at this.’ We are survivors of genocide, we are survivors of displacement, and we are continued survivors of displacement and removal. I love that because when you think about survival and resilience, there is this huge piece of gratitude that exists within that. My family, we celebrate Thanksgiving, we use the term Thanksgiving. I am always the person who likes to interject a little bit of remembrance, ‘Oh, we’re celebrating “survivor’s supper” or “colonizer day.”’ I’ve always been the one who puts that different language in it. My little sister, too. We’re very much outspoken when it comes to advocating and really positioning the other perspective that we don’t always see, our own community perspective. For me, this time of season is about gathering, it’s about gratitude, it’s about resilience, it’s about survival and being grateful for the opportunity to survive and to carry on.

This timeframe, for Kumeyaay people, is our new year. Our new year is in September. It’s the beginning of harvest season and that’s how we start our calendar, is in the fall. So, for us, we start the season with gatherings. We start the season with community, and it’s always been community that drives all of that, no matter what season we’re in. I think, ‘Well, what a beautiful way to remind us, when we come into the season, that it’s all about familial connection and community connections.’ When you look at that intersectional story of, ‘Why do we celebrate Thanksgiving? What is the beautifully wrapped picture of what it means to be thankful? What are you thankful for?’ I think, no matter which culture you come from, you can find yourself grateful for at least something in your life. Grateful for the opportunity. We think about what’s happening around the world, in the Middle East and in Israel, and it’s disheartening and there’s a lot of intersection about Indigenous solidarity with the people of Palestine. There’s a lot of things like that, when we think about what can we be grateful for here, in the United States, in this space, even though we have a lot of work to be done in the United States, but what can we be grateful for? It’s looking around and looking at our present moment in individual spaces. For me, this time of season is about family. It’s about reminding myself of those who are no longer here and being grateful for their fight, their contribution to their stories and their community spaces because, if it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be where I am if I didn’t have those teachings. It is a full circle. Some of us in our family consider it a day of mourning, a day of grief, a day of remembrance. A very solemn day. I feel like there’s room for both. I feel like we can be in deep, deep grief and, at the same time, carry deep, deep gratitude. That has always been at the full of who I am as a person. It’s coming to understanding and coming to peace with the fact that there is an abundance of grief, abundance of sadness and reflection that comes with this type of period. At the same time, realizing that I’m not there anymore and that I can continue to hold space and reverence for that, and never forget it, and remind people of this timeframe. Remind people of the counter to that and what it should look like.

Having these conversations that we’re having now, we see a lot in the month of November with Native American Heritage Month. Our inboxes are flooded in Native country around this time, with people wanting to do a talk, do a land acknowledgement. It’s like, ‘OK, well, what are you doing beyond this day? What are you doing beyond this month? Where are you really moving out of performance and into action?’ What I would like to see is Indigenous voices, especially in the Union-Tribune. I would like to see a community of Native artists, or someone who is a contributing columnist to your paper. We’re not just the Kumeyaay nation, we are the Quechan, the Luiseno, we are Kumeyaay, we are Cupeno, we are Cahuilla. San Diego County is the most diverse county in the entire country of Native communities and we’re the most densely populated. I don’t know your internal structure, maybe you do have a person, a staff writer who is Indigenous or Native, writing a column. That would be a great opportunity to have someone sharing an Indigenous perspective, constantly, not just in November. I would like to see written, published work within the community by Native voices from the San Diego Union-Tribune.