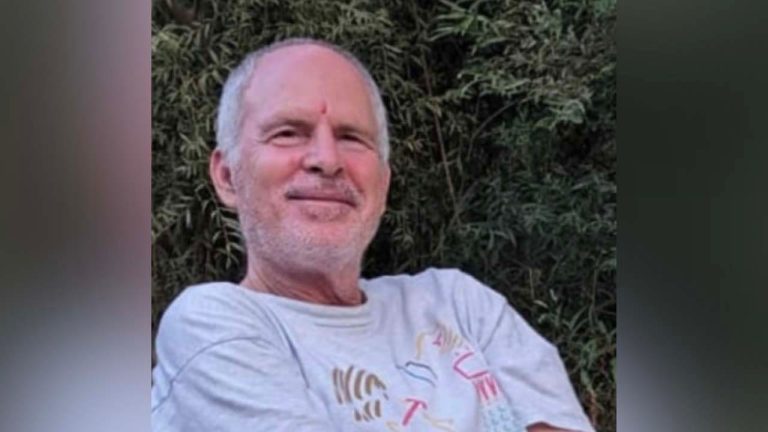

Miller is a local author, professor at San Diego City College, and vice president for the American Federation of Teachers, Local 1931. He lives in Golden Hill.

The last few months have been very good for American unions with impressive contracts for airline pilots, big raises for UPS drivers, strike victories for health care workers, nurses, educators, screenwriters and more. This current and stunning strike wave is unlike anything we’ve seen in the United States since the middle of the 20th century, and it appears to be changing the balance of power between employees and employers. Rather than settling for less, as American workers have done for decades, it seems that many are now finally ready to stand up to the corporate sector and fight.

Former U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich has pointed out that the new labor militancy has helped create “a virtuous cycle — encouraging more workers to join unions and more unions to flex their muscles and demand wage hikes.” Of course, the biggest of the recent wins came in the United Autoworkers’ strike where the union ignored corporate cries of poverty and job loss and achieved 25 percent pay increases, more job security, the reopening of a plant and a road to making the electric vehicle future one that includes solid union jobs.

This win came under the leadership of Shawn Fain, who has rejected the corrupt business unionism of his predecessors and embraced the militant spirit of the Congress of Industrial Organizations of the mid-20th century. Fain, in a The New York Times profile, made it clear that he was not a friend of corporate greed by bluntly stating that, “’Billionaires in my opinion don’t have a right to exist.” Thus, as labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein noted, Fain has learned from the past to help in his fight for a better future for American workers, “He is using more forceful rhetoric than any U.A.W. leadership in a long while, reaching back to the 1930s and 1940s,” he said. “The idea of mutual accommodation with the companies is gone.”

Along with more class consciousness and forceful rhetoric, Fain has also clearly returned to the roots of the United Automobile Workers, whose historic win in the great Flint Sit Down Strike in the 1930s was the impetus that started a wave of union activism that pushed union density to its highest level in American history, helped build the middle class in the United States, and finally brought economic justice into focus as a central part of the unfulfilled promise of American democracy. Labor writer Harold Meyerson recently noted that “as in the 1930s and ’40s, so it is today that the public’s support for unions is at a very high level. The yawning gap between the rich and the rest of us, which was so apparent in pre–New Deal America and so politically salient during the New Deal years, has again become an issue.”

But more than anything else, the United Automobile Workers’ success has reminded American workers of their own power what can be accomplished when working people stand together. As Robert Kuttner put it in The American Prospect magazine: “Fain has produced more than a victory for autoworkers. The United Automobile Workers has demonstrated to the broad public what militant union leadership combined with rank-and-file democracy and solidarity can accomplish for working people in all occupations.”

What is also important about the United Automobile Workers victory is that the union doesn’t see it as the end but as the beginning of a long struggle that will include organizing non-union plants in the United States and building international solidarity with workers in other countries to help fight the outsourcing of good union jobs. And while some have tried to pit industrial workers against climate activists fighting for a sustainable future, the United Automobile Workers, rather than taking that bait, sought instead to bring workers involved in electric vehicle production into the union.

By learning from the past and leaning into the future of the green economy we can stave off the worst consequences of climate change. Thus, the United Automobile Workers is adeptly addressing the intersecting issues of economic inequality and the looming climate catastrophe. As opposed to the fossil fuel industry, which is doubling down on oil rather than investing in a transition to a zero-carbon economy, the United Automobile Workers is leading the way toward a more just and sustainable future for all of us.

This emerging social justice unionism is guided by a larger sense of solidarity and can serve as a light in the present darkness to lead us forward to hope.