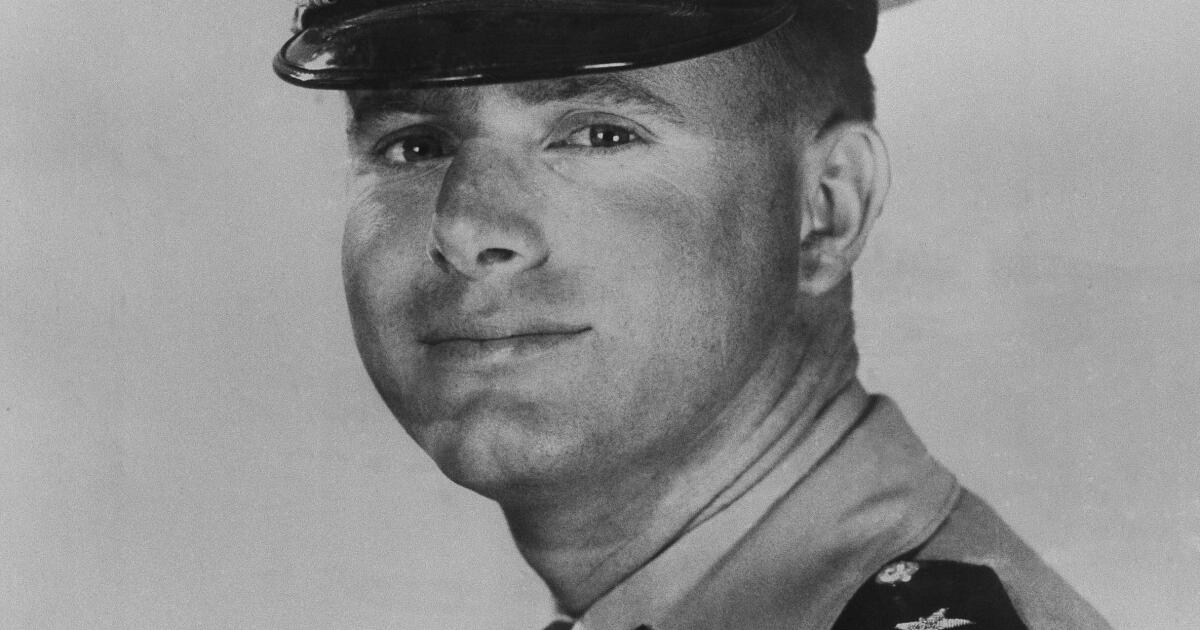

Don Walsh, the San Diego naval officer who squeezed into a tiny submersible with scientist Jacques Piccard in 1960 and dove nearly 7 miles to become the first humans to reach the deepest spot in the world’s oceans, died on Nov. 12 at his home at Myrtle Point, Ore. He was 92.

Walsh’s son, Kelly, told the New York Times that his father, who had lived in San Diego for many years, passed away while sitting in his favorite chair.

The highly risky dive caused astonishment around the world when the public learned that Walsh and Piccard had ridden a crude bathyscaphe, or self-propelled mini-sub, to the lowest point of Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench region of the Pacific on Jan. 23, 1960.

The Trieste, as the bathyscaphe is known, touched down on a relatively soft spot 35,814 feet beneath the ocean’s surface.

Walsh, who was 28 at the time, was accustomed to being in tense situations. He had served on submarines — albeit in much, much shallower water.

“The subs I had worked (on) operated at maximum depths of 300, 400 feet,” Walsh told The San Diego Union-Tribune in 2010. “But I wasn’t concerned. (The Trieste mission) just made me more curious.”

Early news reports said the dive was fairly uneventful. That wasn’t quite true. Among other things, the Trieste’s tachometer, which measured how fast the submarine was descending, broke before the mission even began. Fortunately the vessel, after nearly five hours of falling in the abyss, safely touched down in a silty area.

It was a breathtaking moment. They were in a location that was a greater distance below the earth’s surface than Mount Everest towers above it.

There was reason to believe things wouldn’t turn out this well.

When Walsh and Piccard were about 4,000 feet from the seafloor, they heard a loud bang, suggesting that an explosion had occurred and could result in a leak. While sitting in darkness wearing wet clothes, they soon realized that the bang had been caused by a harmless crack to a secondary window.

“Since our instruments indicated no problems and we were still alive, Jacques and I decided to proceed,” said Walsh, who was known for has calm, understated way of speaking and acting.

Even so, they decided to stay at the bottom for only 20 minutes or so. They wanted to return to the surface before sunset to avoid complications in choppy seas southwest of Guam.

Less than two weeks later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded Walsh, Piccard and project leader Andreas Rechnitzer an oceanographic honor that said, in part:

“This dive and others before it were made in the interest of science and to collect data for the United States Navy in this previously unexplored area of the earth. This — the first penetration of the deepest parts of the ocean — impressively demonstrates that the United States in the forefront of oceanographic research.”

Eisenhower was also alluding to something deeper, and darker. The Trieste was part of Project Nekton, a program that the Navy Electronics Laboratory in San Diego operated to help keep the U.S. on the technological footing it needed in the rapidly deepening Cold War with the Soviet Union.

The NEL studied everything from the durability of ship hulls to the movement of sound through water.

The program seemed tailor-made for Walsh, who was born in Berkeley on Nov. 2, 1931, and developed a deep love of the Navy early in life, mostly from looking at the large assemblage of warships in San Francisco Bay.

He went on to graduate from the U.S. Naval Academy, where he was awarded a degree in engineering in 1954. He quickly became a submariner, serving, for a time, in the role of commander.

Walsh’s next big step came in 1959 when, as a lieutenant, he volunteered to become the officer in charge of the Trieste, which was 50 feet long and 12 feet in diameter. The submersible had been designed by Piccard and his father, Auguste, a Swiss oceanographer, and the Navy had acquired it as a deep sea research vehicle.

There was no glamour in traveling aboard the sub, whose crew sphere was only 6.5 feet wide, making movement difficult.

Still, the view from the porthole during the famed dive was something to behold, at least for a few fleeting minutes. Walsh and Piccard, who died in 2008, saw itsy-bitsy glowing creatures.

“Bioluminescence is rampant in the abyss,” Walsh told National Geographic many years later. “Even out where we were, which is not a very thickly populated part of the ocean, because there aren’t that many nutrients out that far from land.”

The dive made Walsh famous, but that wasn’t the last of his contributions.

He later served on key government committees that explored oceanographic issues worldwide, collaborated with scientists at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and advised other explorers, including filmmaker James Cameron, who dove to the bottom of Challenger Deep in 2012. Walsh also served as dean of marine programs at the University of Southern California.

Walsh is survived by his wife, Joan, his son Kelly, and his daughter Elizabeth.

The Trieste is on public display at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C.