San Diego County will delay the implementation of Senate Bill 43, the new law that expands what it means to be “gravely disabled” in order to give caregivers more time to handle expected increases in emergency department visits.

SB 43, which Gov. Gavin Newsom signed in early October, takes effect on Jan. 1, 2024, but allows county boards to grant themselves deferrals of up to two years. While some counties have already voted to punt the effects of the legislation for the full two years, San Diego County struck a middle ground Tuesday, voting 3-2 to put the law into effect on Jan. 1, 2025.

Supervisors Terra Lawson-Remer and Joel Anderson were in opposition. A proposal by Lawson-Remer to implement SB43 “as soon as possible, on or before Jan. 1, 2025,” did not garner support from board Chair Nora Vargas, who put the item on the agenda.

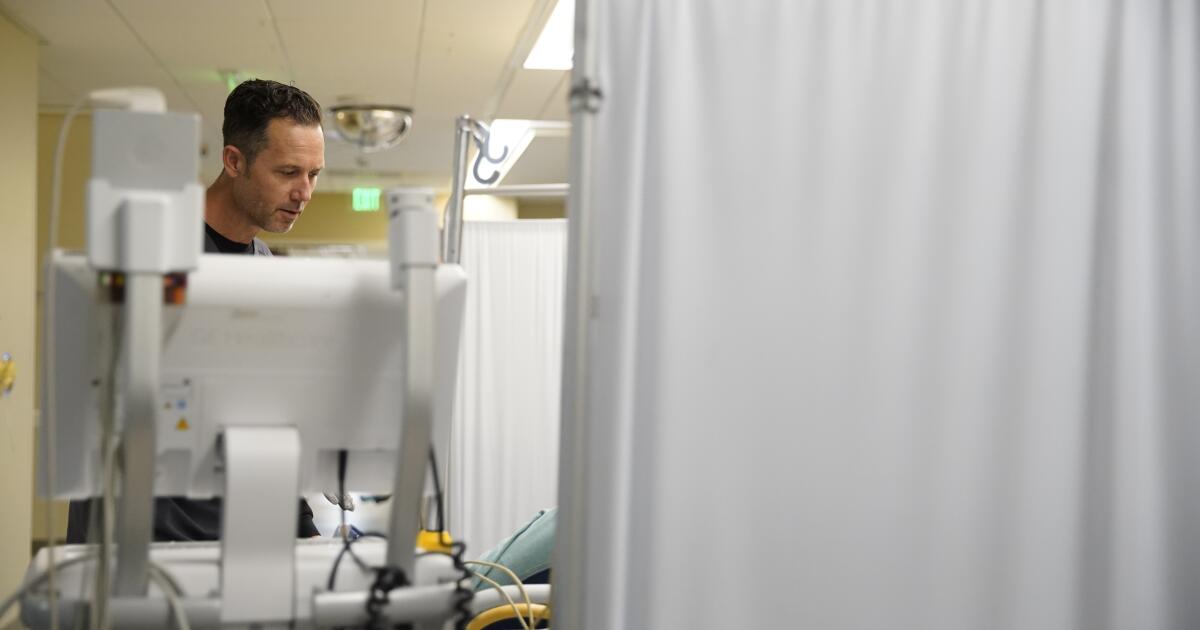

San Diego County’s health care systems pushed hard for a deferment, noting that their emergency departments often operate at or over capacity and could be additionally clogged by broadening the criteria that law enforcement officers and other first responders use to determine who gets detained on so-called “5150” holds.

Current law allows those thought to be a danger to themselves or others or gravely disabled to be picked up and taken to a qualified hospital for evaluation by a licensed mental health practitioner. Today, the standard for gravely disabled is those who can’t meet basic needs for food, clothing and shelter. But SB 43 adds inability to provide for personal safety or necessary care to that list, also adding substance use as a criteria.

While many refer to this new law as being about conservatorship, a legal process in which a judge appoints a person to make decisions on behalf of someone deemed to be unable do so for themselves, getting to that point starts not in courtrooms, but in hospitals.

State law, noted Luke Bergmann, director of behavioral health for the county, requires anyone picked up on a 5150 hold to be treated in a hospital emergency department. That, he and others said, could become a dangerous bottleneck if the number of holds increased dramatically next year.

It is predicted, Bergmann added, that most people detained under the expanded definitions put in place by SB 43 “will have their holds dropped because their intoxications will clear.” In other words, once the effects of drugs and alcohol wear off, clinicians would find no evidence of mental illness that would justify a longer stay in a locked behavioral health unit.

What’s needed, he said, is a plan for how to better refer those suffering from substance abuse disorder to treatment programs outside of hospitals. But, he added, the law comes with no additional funding to accomplish that goal. Absent a plan to make that hand-off, he said, many are likely to be discharged and picked up over and over again, as is already occurring with a more narrowly written definition of who is considered gravely disabled.

“The revolving door at the emergency department for people with substance use disorder will just spin faster,” Bergmann said.

The majority of board members were clearly uncomfortable with the notion of moving forward in the face of so many dire predictions from the health care sector.

Supervisor Jim Desmond made it clear that while he supported the delay, there would be no further extensions.

“I can appreciate the hospital association, (and) everybody, saying, ‘hey, we want to get this done, but we’ve got to do it right, and you need time to build this up,’” Desmond said. “But I’m not going to support future delays — one year, that’s it for me … we’ve got to get this thing turned on.”

Lawson-Remer said she could not support the delay because it “feels way too broad for me.”

She pushed Bergmann to get specific about exactly what he and others will do in the coming year to make SB 43 implementation more successful. Bergmann said his department is already working on implementation of CA Bridge, a statewide program launched in 2018 that seeks to expand medication availability for addiction treatment to emergency departments. Initial doses of drugs that can help manage withdrawal symptoms are linked with consultations with “navigators” to “triple the likelihood that patients will be in treatment 30 days after they leave the emergency department,” according to the program’s website.

Determining how a larger volume of detainees with substance abuse struggles could be handled by expanding the existing system, Bergmann said, tops the to-do list for the coming year.

“SB 43 comes with no new resources for hospitals, substance use treatment providers or county-run public conservator offices,” Bergmann said. “It doesn’t establish clinical assessment criteria that will incline clinicians to extend holds, and it doesn’t do anything to create the operational tools that will actually get people with substance use disorder from emergency departments into ongoing treatment.”

Wanting to make sure they understood what will be done to move toward full SB 43 implementation, the board asked for a report in 90 days on what methods various constituents think will work. That meeting is now scheduled for the board’s second regular meeting in March.

But there is clearly a political cost to any delay where unhoused residents are concerned. The public is very clearly in no mood for additional delays, and the pressure increases the closer a resident is to the places where people live on the streets.

Calling the situation in his East Village neighborhood a “humanitarian crisis,” Giorgio Kirylo, demanded that SB 43 happen now, not in one year.

“You have no idea what it’s like to live in East Village, to see people who are suffering through mental health crisis, or meth crisis as I like to call it, running around with a knife, naked, only to hear a police officer tell you, ‘well, there’s nothing that I can do,’” Kirylo said.

But those expected to care for these patients were equally strident in their comments Tuesday.

Melody Thomas, a registered nurse who said she has been the director of case management and social work at Scripps Mercy Hospital San Diego for seven years, predicted that implementing the law now would not fix anything.

“There are not enough resources for our patients that (currently) meet the criteria for grave disability,” Thomas said. “We have multiple patients on conservatorship waiting for appropriate post-discharge placement.

“Some patients, unfortunately, have been waiting in our hospital for multiple years for the appropriate long-term care beds; it’s rare that we’re able to get a patient to transition from the hospital setting to a substance abuse facility.”