It’s not yet clear whether two people recently found dead in Santee were homeless.

Their deaths haven’t even been definitively linked to Monday’s historic storm.

But the news has already had an effect on people living outside. Michelle Hennings, 47, was sitting in a tent by the San Diego River Thursday when a visitor asked if she’d been hurt by the flooding.

“We didn’t really lose anything,” Hennings said. Two bikes remained on the hill, as did a mattress in her tent. But then, unprompted, Hennings said she’d heard of others who’d been lost in the water, including one woman who disappeared in El Cajon.

As she spoke, Hennings began to cry.

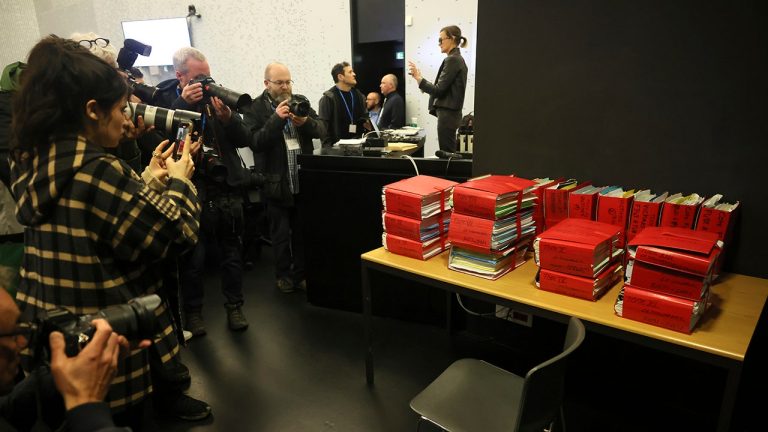

Just days after heavy rain displaced hundreds of people from their homes, shelters and camp sites, a small army of volunteers gathered before sunrise for the region’s annual homelessness tally.

Oceanside Police Officer Josh Ferry participates in the annual point-in-time count of people experiencing homelessness on Thursday.

(Ana Ramirez / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The wind was cool and skies were cloudy. A light mist fell in North County.

The weather has always affected how many individuals can be found during point-in-time counts, yet this year’s effort took place in an especially changed landscape. One designated camping area had been temporarily evacuated Monday while another shelter downtown may not be salvageable. Plus, the homeless population was already in flux since San Diego passed its camping ban, and the tally could eventually show whether neighboring cities have seen a corresponding rise in people on the street.

A little before 5:30 a.m. in Chula Vista, Officer Kevin McLean had already tallied dozens of encampments when he approached one tent near an interstate. Inside was David Garcia, just 22 years old.

“Have I talked to you before,” the officer asked.

“Yeah, you have,” Garcia responded. The young man said he’d served two years in the Navy before receiving a medical discharge and had now been homeless for about four months.

McLean, who is part of the police department’s homeless outreach team, wrote down his number on a piece of a paper. “Please, reach out to me, OK? You’re too young to be out here.”

Tarps and tents are prevalent in the southwest part of the city, and local leaders are considering their own camping ban. Chula Vista does have a shelter near the Otay Valley Regional Park and officials have purchased a motel to convert into more permanent housing.

One man along Industrial Boulevard asked McLean about the region’s new safe sleeping sites, where people can legally camp.

“How can I get into tent city,” he said.

“That’s in San Diego,” the officer said.

Graham Mitchell, El Cajon city manager, and volunteer JennaMarie Glenna speak with a homeless person sleeping under a bridge in El Cajon on Thursday.

(Alejandro Tamayo / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The federally mandated count is overseen by the Regional Task Force on Homelessness. About 1,600 people had agreed to conduct the tally across 43 parts of the county, a landmass similar to what was surveyed a year ago, according to spokesperson Jordan Beane.

Last January, a record high 10,264 homeless individuals were estimated to be in shelters, vehicles and on local streets. That was a 22 percent increase from the year prior and included a growing number of women, veterans and older adults.

Volunteers used a phone app to ask questions (“Is this the first time you’ve been homeless?” “Do you struggle with mental health issues?”) and people who took the survey received gift cards. Those who declined still got fresh socks.

In East County, several said they’d ended up outside after losing jobs during the pandemic.

David Richard Jackson, 38, unhoused for 16 months, speaks with the volunteers in El Cajon on Thursday during the annual point-in-time count.

(Alejandro Tamayo / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

David Jackson was walking past an El Cajon car wash with a scuffed skateboard when he stopped to talk. The 38-year-old said he’d worked for years at a Sherwin-Williams before being let go in 2020.

“Nobody was buying paint,” Jackson said.

At a lot by Wells Park, two people sat in a VW Beetle. Diana Stumetz, 53, was in the passenger seat near her “babies:” four chihuahua dachshund mixes.

Stumetz said they’d been living in a mobile home park until the place was sold and the family evicted. Staying in hotels just drained their savings.

She now spends days in the park with others who’ve lost homes. “They see me as a mom — the youngsters,” Stumetz said. “I help them fill out their welfare papers.”

Further north, police said development in Oceanside appears to have pushed people out of downtown and into surrounding neighborhoods.

David Napoli, 38, woke up in a parking lot by Oceanside Boulevard. He was in the area to visit a methadone clinic, which can treat opioid addiction, yet steady work was hard to find. Napoli said his identification papers had been stolen, and being born in Germany to a military family had made a new birth certificate tough to track down.

The point-in-time count is just one of several ways to calculate homelessness. The regional task force also releases monthly reports showing a steady rise in people asking for help while the Downtown Partnership has reported sharp drops in San Diego’s urban core. Then there’s the San Diego River Park Foundation, which has seen increases along waterways.

Perhaps no area was more affected by the recent storm than the riverbed.

Rachel Downing (r) leads a team of volunteers working along the San Diego River in Santee for the annual point-in-time count.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Last week, the National Weather Service repeatedly estimated one part of the San Diego River to be about 2 feet deep. Within hours Monday, the water shot up to nearly 12 feet.

There was still a steady current Thursday when three staffers from the foundation descended into Santee’s Mast Park. Muddy paths often disappeared into dark water, where lines of submerged shopping carts served as makeshift handrails. One had a printed advertisement on the front which read, “You may need a bigger cart.”

The group used a Sharpie to mark camp sites they found on a map. Surprisingly, it looked like most long-term encampments had survived the flooding.

Near one tent, James Lombardo, 67, sat on an overturned tub. Smeared mud on a nearby stack of drawers showed that the area had recently been under water.

Rachel Downing speaks with Charles Lombardo, who lives in one of the encampments along the San Diego River in Santee. Downing was a volunteer participating in the annual point-in-time count on Thursday.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

When Lombardo was offered new socks, he immediately kicked off his left boot, revealing a foot with only four toes. He nodded toward the missing appendage.

“I’ve been looking for that dang thing,” he joked. “If you find it, let me know.”

His big toe had been amputated after a rusty nail gave him a blood infection, he said. Lombardo mostly felt lucky to be alive.

Some structures along the river were elaborate. One had bookshelves, a brick floor and a hole cut into an overhead tarp that served as a skylight.

There were also fire pits.

Rachel Downing, a program manager with the foundation, stepped into one camp site that looked partially burned. A statue of the Virgin Mary stood in the middle, blackened and cracked.

“Good morning,” Downing said. “Is anybody home?”

Birds sang from treetops.

“We’ve got a $10 gift card to 7-11 if you want to participate in our census,” she said.

Downing waited 10 seconds, then 20. There was no response.

Rachel Downing speaks with Nick, 41, who lives in one of the encampments along the San Diego River in Santee. Downing was a volunteer for the annual point-in-time count on Thursday.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)