Late one Saturday night in May 2018, an explosion rocked a Spring Valley home, sparking a fire that sent the resident to a hospital with third-degree burns to about 30 percent of his body.

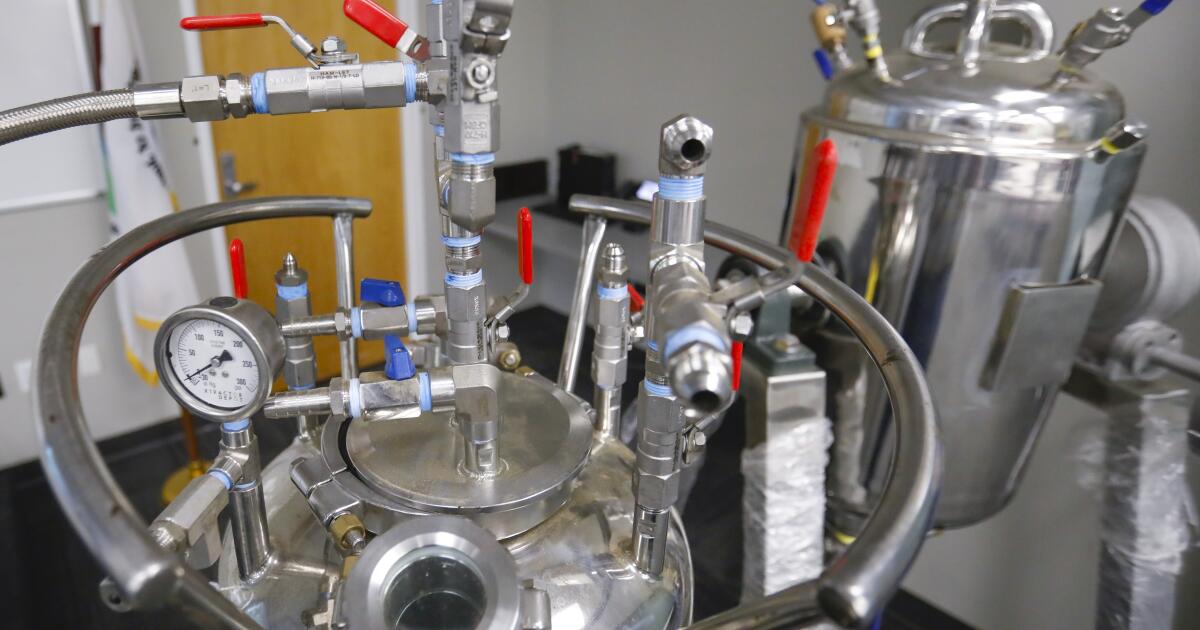

After firefighters doused the flames, they discovered the home contained a butane hash oil extraction laboratory. Such labs use butane, a highly combustible gas commonly used in lighters and camp stoves, to extract a potent, waxy cannabis concentrate known as hash oil or honey oil from marijuana plants. It wasn’t until a few months later that agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration learned the Spring Valley lab was linked to a much larger, more sophisticated hash oil extraction operation — one that posed the same explosive threat to the public.

On Friday, one of the leaders of that operation was sentenced in U.S. District Court in San Diego to three years in federal prison. Ryan Buenaflor, a former college football player from Chula Vista, was the last of eight people to be sentenced as part of the operation.

Buenaflor’s sentencing also marked the end of a series of federal prosecutions launched in 2018 and 2019 that at the time mirrored a growing trend of large, sophisticated hash oil extraction labs that law enforcement agents had discovered — either through investigations or after explosions — around the county. But in the years since, authorities have discovered fewer hash oil extraction labs, the DEA has disbanded its unit that led such investigations and federal prosecutors have not charged any new cases linked to similar labs.

While hash oil extraction labs have not completely disappeared from San Diego County’s illicit drug scene, the apparent drop off in the number of such labs has made the public much safer, according to authorities.

“People figured out it wasn’t worth it,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael Wheat said Friday.

It’s still difficult to pinpoint exactly why authorities have discovered fewer butane extraction labs in recent years, though theories abound.

Gretchen von Helms, Buenaflor’s defense attorney, attributed it to the aggressiveness of Wheat and law enforcement agents who “have shut down that type of business.” Wheat agreed that prosecutors “(dropping) the hammer on people” may be one factor. And a sheriff’s sergeant who works on an undercover marijuana enforcement unit said the continuing evolution of California’s legal cannabis market has likely played a role.

“You have more licensed, legal dispensaries throughout the county, whereas five or six years ago that wasn’t the case,” said the sheriff’s sergeant, who asked not to be named because of the sensitive nature of the undercover investigations he and his team is involved in. “Now that you can go buy (concentrated cannabis) at a dispensary, maybe less people are experimenting with home extractions.”

Federal authorities have said that hash oil extraction labs only began popping up in large numbers across San Diego County in 2013. The next year, the DEA seized 55 such labs, eight of which had exploded or caught fire. The number of seizures steadily declined over the next several years before ticking back up in 2018 and 2019.

Authorities at that time made an effort to warn the public about the dangers of such labs, saying they had seen them growing in sophistication.

“What’s really of concern is how big these labs are compared to what we might have seen back in 2013 and 2014,” Steven Woodland, who was then the assistant agent in charge of San Diego’s DEA field office, said in 2019.

Cannabis runs down the street outside a Mira Mesa home on May 5, 2019, after a butane hash oil lab inside the house exploded and sparked a fire, injuring three people.

(K.C. Alfred/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

In the months prior, an explosion inside a Mira Mesa home badly injured three people, blowing the home’s garage door off and sending cannabis buds flowing down roadway rivers as firefighters fought the blaze. That same month, a man was injured in El Cajon when a lab exploded inside a vacant used car dealership.

There was also the DEA investigation at the center of Friday’s sentencing.

In September 2018, DEA agents and hazmat crews in full-body protective gear raided an industrial building on Hancock Street near San Diego International Airport where investigators had learned hash oil was being processed and distilled into vape pens.

Federal agents raided a suspected drug lab on Hancock Street on Tuesday and seized “a large quantity” of THC extract.

Other agents simultaneously served warrants at warehouses on opposite ends of the county — one in Oceanside and one in Otay Mesa just feet from the border — that housed the large, complex systems used to extract the hash oil.

The trio of raids, part of a monthslong investigation that relied on two informants, resulted in the seizure of more than 8,700 pounds of cannabis and more than 185 pounds of raw and refined concentrated cannabis, as well as seven large extraction systems and dozens of butane tanks. Buenaflor and three people he worked with at the Hancock Street processing site were charged in one case; brothers Bryan and Sean Zigler and two people they worked with at the extraction sites were charged in another case.

All of the defendants have since pleaded guilty and been sentenced, half of them to terms of probation or time-served. Bryan Zigler’s seven-year sentence was the longest. Buenaflor’s sentence, handed down Friday by U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw, was the second longest.

Buenaflor told the judge that he was a serial entrepreneur who was trying to take advantage of the “green rush” that occurred after Californians voted to legalize cannabis in 2016. But he said he listened to bad advice from an attorney, didn’t properly educate himself on the differences in state and federal laws and didn’t initially know the dangers of butane extraction labs. He also said he was sorry about the man who was burned at the Spring Valley home linked to his operation.

In arguing for a more lenient sentence for her client, von Helms offered her opinion of why law enforcement agents have discovered fewer butane extraction labs in recent years.

“No one is doing illegal extraction with Butane in California because prosecutors like Mr. Wheat and the agents have shut down that type of business,” von Helms wrote in a sentencing document.

It’s a self-serving argument — deterrence is one factor a judge must consider when crafting a sentence, but von Helms argued it need not be a consideration in her client’s case. She wrote that “in 2024 (no one) is manufacturing butane marijuana” and therefore no one would be deterred by a stiff sentence for her client.

Wheat told the Union-Tribune after Friday’s hearing that he had prosecuted several hash oil extraction lab cases in 2018 and 2019, but has not been referred such a case by law enforcement since then.

A member of a DEA task force looks over an El Cajon hash oil extraction lab that partially exploded in June 2019, causing a fire that injured a man in a warehouse behind a used car dealership.

(Courtesy of DEA San Diego)

It’s difficult to say exactly how many fewer butane extraction labs have been discovered in recent years. In 2021, the local DEA field office disbanded the task force that investigated such labs, thus ending its practice of tallying all butane extraction lab seizures in the county. Now each of the county’s various police agencies and the Sheriff’s Department, which polices several cities and the county’s rural areas, maintain its own seizure statistics.

The undercover sheriff’s sergeant said his unit, the Marijuana Enforcement Team, spends about 75 percent of its time investigating large-scale illegal cultivation operations. They sometimes find partial evidence of extraction labs at grow sites, but the large, industrial-size extraction labs have become more rare.

“We’ve seen a few complete ones, a few fragmented ones,” the sergeant said. Some have been in homes, others in commercial buildings.

The Sheriff’s Department said its deputies discovered five labs in 2021, two in 2022 and another five last year.