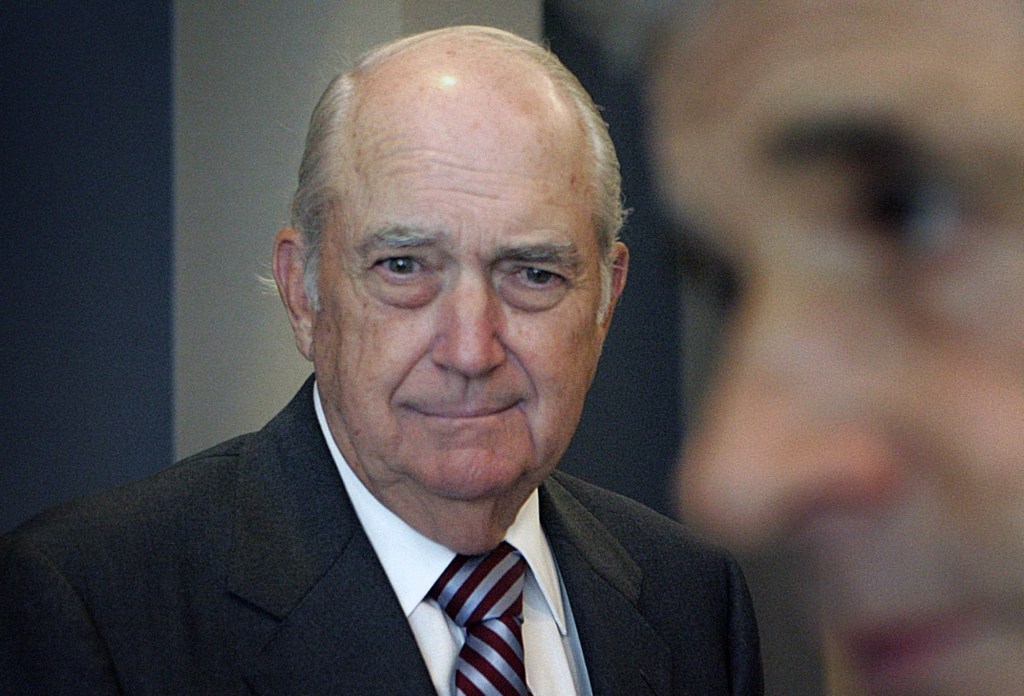

Former U.S. District Judge James Lawrence “Larry” Irving, who resigned his lifetime position in disagreement with sentencing guidelines and who later mediated a then-record $7.2 billion settlement in the Enron case, has died. He was 89.

Irving died in his sleep at his Coronado home on Nov. 20, his family said.

The San Diego native left a long legal legacy, including eight years as a federal judge in San Diego, appointed in 1982 by President Ronald Reagan. In the 1980s he was considered as a top prospect to be the director of the FBI, and in 1990, the Los Angeles Times said Irving was “widely regarded as one of the keenest judges in California.”

Friends, family and colleagues say Irving was thoughtful, open-minded, respectful and “incredibly savvy.” After Irving brokered the deal that saw the departure of embattled then-San Diego Mayor Bob Filner in 2016, one attorney said he had a “velvet gavel,” a phrase that later became the name of Irving’s biography.

“If you sat next to him on an airplane you would never know he was a federal judge, or was as impressive and successful as he was. Unpretentious. Very humble. Wise,” said Irving’s former law partner, attorney Doug Butz. The two men shared a 50-plus-year friendship.

As a judge, Irving presided over several notable cases, including the money-laundering case of San Diego businessman Richard Silberman, as well as bankruptcy litigation from an $80 million Ponzi scheme and a cocaine-trafficking case involving 98 defendants.

In 1990, Irving made a stunning announcement: he was resigning from the bench primarily because he disagreed with federal sentencing guidelines requiring mandatory minimum sentences. He lamented the loss of the discretion for judges to fashion sentences.

“It really tugs at your heart when you have to sentence a first-time offender to a mandatory minimum sentence of say, 10 years, 15 years with no parole,” Irving told the Evening Tribune, a precursor to the Union-Tribune.

He had challenged the guidelines in 1988 as unconstitutional, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld them the following year. His decision to step away drew national media attention.

Irving later moved into work as a mediator and became “of counsel” — a legal advisor of sorts — to Butz’s firm. “He had an understanding of what a fair resolution would look like,” Butz said.

He shepherded high-stakes cases beyond the massive Enron fraud scandal settlement, including mediating an agreement in the Lincoln Savings and Loan scandal and in a suit stemming from San Diego’s pension crisis. In 2016, the Union-Tribune reported Irving said he had mediated settlements tallying more than $11 billion over his career.

Irving was born in San Diego in February 1935. After he graduated from Point Loma High School, he headed to University of Southern California, earning his undergraduate degree in business administration.

He joined the Army and did a stretch as a tank driver in post-World War II Germany — and would later rather wryly note he quickly rose to the rank of private first class and stayed there, son Craig Irving said.

With his GI Bill, he headed back to USC for law school, graduating in 1963 and quickly passing the bar.

Irving came home to San Diego and went into civil litigation for the next roughly 20 years, first working at Higgs, Fletcher & Mack before hanging out a shingle as Jones, Tellam, Irving & Estes, then as Irving & Butz.

In his private life, Irving was an enthusiastic golfer, taught his sons to hunt and fish, and was a dedicated Trojan fan.

“He was a great man,” Scott Irving, 64, said of his father. “Honor and integrity were important traits to him.”

Craig Irving, 62, said his father also had a great sense of humor, and that, true to his nature and oath, the elder man never shared the inside details of his legal work. “My dad could have written one hell of a book, but all those secrets went up to heaven with him.”

Throughout it all, he was fiercely devoted to wife Frances Evelyn Johnson — they met when he was 22, Fran was 20, and married in 1961 — and their family. He is survived by Fran, their sons Scott and Craig, eight grandchildren and a great-grandson.

In accordance with the judge’s wishes, there will be no services.