Posted February 3, 2025 at 1:33 pm EST.

When an attractive young woman named Millicent first messaged me on Instagram a little over a year ago, I was skeptical. After all, I’d received dozens of messages like this before from strangers on Instagram and other social media platforms, mostly consisting of random queries or comments on my posts, and I knew that most, if not all, were some kind of scam, the details of which I could only imagine. And as a longtime business journalist, being skeptical was my stock in trade.

But something about Millicent’s message caused me to lower my guard. For starters, her Instagram profile showed that she had a lot more followers than people she was following, which signaled to me that it wasn’t a quickly executed profile that someone had just created to start following lots of people so that they would follow her back. Secondly, her photos, which went back at least two to three years and showed her in glamorous locales like Paris and Florence with her companions, had what looked to be authentic comments from friends and followers, many of which included responses back from her. Finally, her note to me asking about one of my photos in which I appeared to be wearing Chinese military garb seemed rather innocuous, and one whose backstory would be fun to recount if she turned out to be a real person.

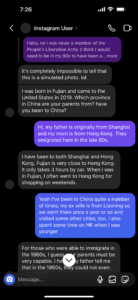

So on a lark, a few days after her initial message, I responded: “Haha, no, I was never a member of the People’s Liberation Army. It’s from a meme generator that imagines what I would have looked like.”

An hour or two later, Millicent wrote back, saying it was impossible to tell it wasn’t a real photo, and relating that she was from Fujian province in China and had come to the U.S. in 2019. She asked me questions about my background and whether I’d ever been to China before, and when I told her that my ex-wife was from Northeast China and so I’d visited the area a number of times, she said she had learned how to ski in that region.

Her Chinese name was Chen Yuting, and her father was Chinese and her mother was Japanese. When she had first come to the U.S., she lived in Irvine, California and now lived on Long Island for work. We moved on to other topics such as what it was like growing up in the U.S. and our favorite foods. She complimented me on how good I looked for being in my early 50s, and when she told me she was 37, I teased that she looked fresh out of college.

It had been a while since I’d been in a relationship, and messaging this sophisticated and attractive young woman who was curious about me was exciting and validating. Eventually, Millicent asked about my job and when I told her I was a crypto journalist, she mentioned that she had lost more than $100,000 trading crypto because she had gotten greedy and didn’t listen to her aunt’s advice. I told her I was sorry about her losses, but she said she considered it a learning experience.

Before I knew it, three hours had passed and around midnight, I told her I needed to sleep but I would love to chat with her again soon. She asked to connect on WhatsApp and gave me her number. Excitedly, I shared mine.

The next morning, I did a little more research. Millicent had mentioned that she was an executive at a beauty company. Her profile, which contained several photos of her with colleagues at industry trade shows in Asia, included the firm’s name and its web address. The slick-looking home page, which was mostly in Korean, featured skin care products for sale. Finally, the area code of her phone number—607—turned out to be in southern New York—not Long Island, but not so far away as to ring any major alarm bells.

Everything seemed to be above board and I was thrilled that through the magic of online communities, I’d met a really interesting and attractive woman. The thought that Millicent might have been trying to seduce me as part of an incredibly elaborate organized scam never even entered my mind. But it should have.

Pig Butchering 101

If you’ve been in crypto for a while, you’ve probably heard about pig butchering. It’s a brutal term for a heartless practice in which scammers meet their victims online and romance them, before persuading them to put significant amounts of money in a fake investment, typically crypto. Then, the scammers abscond with the proceeds and ghost their victims. It’s one of the fastest-growing scams in the world, according to the FBI, victimizing tens of thousands of Americans a year and bilking them out of an estimated $2.3 billion from 2021-23 alone. And those numbers are likely significantly understated, given the reluctance of many victims to report the crime out of shame.

Read more: 8 Ways to Protect Yourself From Being Victimized by a Pig Butchering Scam

Pig butchering appears to have originated in China around 2016 and soon expanded to Southeast Asia, before taking off worldwide during the pandemic when everyone was doing almost everything online. In the last few years, scammers based in Asia have increasingly targeted Americans in wealthier cities and states in the U.S. because “that’s where the money is,” according to Troy Gochenour, a spokesperson for the Global Anti-Scam Organization (GA-SO), which now spends most of its time these fighting pig butchering since it’s become so prevalent.

According to the Beijing News, the phrase “pig butchering” comes from the name the initial scammers in China gave their scheme; in Mandarin, it’s “sha zu pan,” or literally, “pig killing game.” The idea is that the scammers are fattening up their victims, or “piglets” as they’re called, until they’re slaughtered for their riches. The metaphor is extended even further; places like social media and dating sites where potential victims can be identified and approached are referred to as “pig troughs,” while the scripts and routines scammers use to deepen relationships with victims are known as “pig feed.”

The scams almost always involve crypto for several reasons, the first being that crypto is highly liquid and acts like cash in that transactions are not reversible. “Criminal actors often exploit the inherent characteristics of digital assets to move and launder funds quickly to try to evade law enforcement,” Claudia Quiroz, the director of the National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team (NCET) at the U.S. Department of Justice, told me.

The second reason why these scams typically utilize crypto is that the assets play well into the narrative of quick riches. Quiroz pointed out that it’s well-known that a lot of people have made a significant amount of money in crypto, so there’s a fear of missing out.

And finally, since crypto can be complicated for lay people to understand, the scammers can both impress and confuse their victims with jargon; in the early years of the scheme in the U.S., scammers almost invariably told victims that the type of investments they were recommending and profiting from was a form of passive investing known as “liquidity mining.”

My own familiarity with pig butchering came from reading an in-depth article at a crypto publication for which I was freelance editing, just a few weeks before Millicent first contacted me. The article described how the actual perpetrators of the scam—or at least those carrying out the seducing of the victims—are almost always themselves victims of cons that lure them in with fake job opportunities in Southeast Asia. But when they arrive to start work, the scammers’ passports are confiscated and they’re forced to work backbreaking hours in gigantic compounds, sitting at computers and hustling to engage potential marks online and fatten them up for slaughter.

When I asked GA-SO’s Gochenour about why pig butchering operations “employed” so many workers in this way, he explained that it’s because the schemes are so labor-intensive. “Think about how many people that they have to message every day to get a couple who might fall for their scam,” Gochenour said.

Unfortunately for me, the article I’d read focused on the victims forced to execute the scammers’ schemes, and didn’t go into detail about how they approached and deepened their relationships with their marks. So while I knew that pig butchering was a well-organized and fast-growing romance scam, I didn’t know how the schemes worked and how psychologically sophisticated they were.

Baiting the Hook

The next day, I shot Millicent a WhatsApp message: “Ni hao,” Mandarin for “hello.” An hour or two later, she responded with a voice message: “Zao shang hao, Wang,” meaning “Good afternoon, Wang.” She wrote that she had been up at 4 a.m. dealing with a work call from China, which led her to miss her morning meeting. We talked about our respective jobs and work schedules. I sent her an article I’d written; she was duly impressed and said that I must be very smart.

Since it was nearing dinner time, I asked what she was eating that night and she replied that she was driving and would show me later. Soon after, she sent me a photo of some elegantly plated sushi at a Manhattan restaurant called Sushi Muse, as well as a screenshot of its location on Apple Maps.

After she got home, she sent me another Apple Maps screenshot with a pin in it, this time for a location on Applegreen Drive in Old Westbury on Long Island, explaining that while she enjoyed the city, she preferred living in the suburbs. We chatted a bit more about our lives, and before saying good night, I said I was wondering how she had come across my profile on Instagram. “You appeared on my recommended homepage, and I am a very curious person, so I clicked on your homepage and saw the photo of the People’s Liberation Army,” she replied. “Ahh interesting,” I wrote, adding “Well, I’m glad you found me 😀”

The next morning, I messaged her to say hello and we soon began chatting about our plans for the day. The Mid-Autumn Festival, a major Chinese holiday akin to Thanksgiving, was coming up and she asked me if I celebrated it. That got us talking about Chinese culture and food, and then we were off to the races, with her sending me pictures of the mooncakes she was preparing to give to her employees for the festival, and me telling her about my parents and how we had celebrated it growing up. Millicent asked about my daughter, and mixed in with all this was some flirtation, leavened by emojis and GIFs.

Thus began a routine in which we’d message for an hour or two every day, usually in the late afternoons when my workday was drawing to a close, and then again before bedtime. At one point, Millicent suggested we come up with nicknames for each other, and we eventually settled on “princess” for her and “knight” for me. “Because you are a knight, of course you only protect the princess,” she wrote. “I feel very safe this way.” At times, I called her my “xiao gong zhu,” meaning “little princess” in Chinese, and many of the emojis and GIFs we sent to each other played off these nicknames.

Looking back at our message history for those first two weeks, two moments stood out for how they deepened our connection.

The first was when Millicent asked me in an audio message whether I could sing anything in Chinese. I told her there was one classic song in Mandarin that I kind of knew—one called Yue Liang Dai Biao Wo De Xin (“The Moon Represents My Heart”) that had been popularized in the late 1970s by the iconic Taiwanese singer Teresa Teng. Millicent recognized it and asked when I was going to sing it to her. “It’s been a long time since anyone sang to me alone,” she wrote. “I believe your voice must be very nice 😉.” I playfully replied “Haha, maybe when we meet for a drink. Or on WhatsApp if I get drunk one night 😁”

Millicent teasingly suggested I drink that night, saying “it’s not a gentleman’s style to refuse me at my first request 😆.” That evening, I looked up the Romanized Chinese lyrics for the song and found a karaoke version sans vocals. I printed the lyrics and practiced the song several times, getting caught up in the excitement of doing something so creative and personal that would surely make a big impression on Millicent. When I finally felt confident enough, I hit play on the video and recorded myself singing the song on the Voice Memos app of my iPhone. The next day, I sent it off.

Her reaction was emphatic. “Can you give me an autograph?” she wrote, addressing me by my Chinese name. She complimented me on my voice and commented that “it’s been a long time since anyone sang to me.” She then asked about where I had learned my (limited) Chinese, which got us talking about our formative experiences growing up in the U.S. and China and some of the challenges we had each faced. She mentioned that she had gone to Tsinghua University in Beijing. I told her I knew Tsinghua was often referred to as the MIT or Stanford of China. “So you’ve got beauty and brains 😊,” I teased. “Beauty was given to me by my parents, and wisdom was given to me by my grandfather and aunt,” was her whimsical reply. I had to pinch myself, feeling so lucky to have met Millicent.

The other notable moment—and one that would become even more significant later—occurred early on when I mentioned that I had an older brother and asked whether she had any siblings. She said she had a sister who had died in a car accident in 2016 when she rear-ended a truck, adding ominously that it happened “because of my reasons.” I told Millicent how sorry I was to hear this and asked what happened. Before answering, she sent me a photo of the two of them as toddlers, and then explained that the accident “wouldn’t have happened to my sister if I hadn’t been on a video call with her and she wouldn’t have been distracted.” I told her again how terrible I felt for her, and tried to reassure her that what happened wasn’t her fault.

Millicent responded that although it still made her sad, she tried to keep it in perspective and view it as one of the challenges in life we all have to face. “I have read this sentence in a book: Everything you experience in this world has been arranged. You have to experience it and feel it. What you get is the level you must pass,” she wrote.

As our conversation wound down, she said that she hadn’t talked to anyone about her sister’s accident for a long time, and that maybe it was the fact that we didn’t know each other that well that allowed her to be so open with me. “I like this identity,” she wrote. “I don’t have to worry about you because we are in different circles and we have never met. I can say what I want without any hesitation.”

I left the chat feeling incredibly connected and tender towards her, as well as impressed by her resilience and philosophy on life.

Jiggling the Line

Millicent and I continued to get closer. At times, she treated me in an almost maternal way, giving me food and drink tips for my health, and sharing recipes. One time I shared a short video of my daughter at her piano lesson, and Millicent, whose Instagram profile contained some videos showcasing her piano skills, gave detailed feedback on my daughter’s technique. Throughout our conversations, she was always respectful of my time and commitments, such as having to make dinner or spend time with my daughter. She almost always responded quickly and directly to my questions about her past and everyday activities.

Given how things had progressed, I pushed to try to meet in person, and while she agreed it would be nice, she told me she didn’t want to give me the wrong impression by meeting me so soon. She also told me she was traveling for work, so I satisfied myself with the connection we were forging via messaging for the time being.

Occasionally, Millicent mentioned her aunt, with whom she was close and who lived in Boston where she ran a small crypto trading business. Looking back, Millicent’s talk about trading crypto should have been a huge red flag, but I was already smitten and if anything, thought it was enterprising of her to be investing significant amounts in crypto. It fit with her sophisticated background and signaled that she was a person of means, not someone who might want to scam me.

At one point, I asked Millicent to do a video chat and she gently deflected my question. But when I asked again, she told me that because of her role in her sister’s accident, video chats made her feel uncomfortable. Of course I understand, I told her, feeling bad that I had brought up an old wound.

After two weeks of intimately messaging Millicent daily, I began thinking that we were in some kind of relationship. My daughter, who had caught me texting her several times, even asked me if she was my girlfriend. “I don’t really know, to be honest—maybe?” I said.

I mentioned the burgeoning relationship to some close friends, reassuring them that I was aware there were reasons to be suspicious, but I denied the possibility this was a scam based on my research into her, the personal details she had provided, and the way our conversations had gone. While my friends noted it was an unusual situation, they seemed genuinely happy and excited for me.

The one person who remained skeptical was my brother, who thought Millicent’s reluctance to video chat was suspicious, despite her reasoning. But I wore him down, insisting that it would have been impossible to have made up all these life details backed up with photos and other evidence. I also pointed out that Millicent and I had been messaging for hours every day for more than two weeks, and she had never once mentioned wanting money or anything else from me (incredibly, I even recall remarking to him that if this was some kind of scam, it was the most elaborate long con ever). In the end, he wished me luck, although I could hear lingering doubt. Looking back, I realize I so wanted Millicent to be real that I discounted any evidence to the contrary. And in my defense, the scammers were so skillful and thorough that I glossed over any concerns.

Around this time, Millicent and I had an audio chat on WhatsApp. The sound quality wasn’t great, though, and Millicent had a strong accent that made it challenging to understand her. I tried using my limited Mandarin to converse, but it really wasn’t up to the task, and eventually we gave up after a few minutes of a static-y, stop-and-start conversation. After that experience, it seemed best to stick to messaging until we got to meet in person.

Preparing to Reel Me In

After about two-and-a-half weeks of intense daily messaging, Millicent mentioned that she was going to Boston for a week to visit her childless aunt, who was thinking of leaving her crypto business to Millicent. The night of her trip, she sent me a photo of her in her car waiting for her aunt.

The next day, Millicent told me about some meetings she had with her aunt and her employees about their trading strategies, and we continued to talk about our lives, our hopes, and our growing feelings for each other. I asked her if she had told her aunt about me, and she said she had mentioned me quite a bit and her aunt had teasingly asked Millicent if she was in love. “I blushed and didn’t know how to answer her,” Millicent admitted.

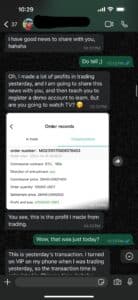

Two days later, Millicent told me she had good news—she had made $42,000 trading on her aunt’s direction the night before. She explained that the strategy was based on highly leveraged bets on bitcoin’s short-term price movements, and that she and her aunt otherwise kept their funds in USDT. She then suggested I set up a demo account on the UK-based exchange she and her aunt used. “If you do well in trading, I can consider teaching you to register a real account to make real money,” she added.

I told her that because I was a journalist covering crypto, I didn’t feel comfortable investing aggressively in the space, especially not leveraged or short-term bets because of the potential I had to get access to non-public information and not wanting that to ever become an issue (I own some bitcoin and ether, but never trade either). Millicent said it shouldn’t be a big deal since crypto is mostly unregulated and we weren’t doing anything illegal, but she didn’t push it and encouraged me to set up a demo account for fun.

Even though I had no intention of ever trading real money, it seemed harmless, so I set up a demo account with a fake $100,000 deposit on the exchange she suggested. The one thing I remember about the process is that the exchange’s customer service rep was over-the-top in their solicitousness, telling me when I thanked them that “of course, it’s my utmost duty to help you as a customer.”

From there, Millicent explained we would choose an amount to invest, bet on BTC’s price direction, and a time interval of either 30, 60, or 120 seconds, and then see whether we had made a profit or a loss. I wagered $10,000 that bitcoin’s price would increase over the next 60 seconds, and I had made $2,700 on the trade. I shared my screenshot with Millicent, who sent me an applause emoji. “Congratulations, you are very smart my knight,” she wrote. I made several more bets, mostly winning ones, and in the end made about $11,000 in paper profits. Millicent teased that maybe her aunt should leave the business to me, rather than her.

“You are awesome, this is just a demo account for you to learn how to operate,” she continued. “But you cannot trade real money on your own without my permission. I don’t want to see you lose money.” Soon, however, we returned to talking about our lives, and more importantly from my standpoint, what we were having for dinner.

Wriggling Off the Hook

The next day, Millicent and I bounced from talking about traditional Chinese folk songs to our favorite basketball players to our favorite traits in the other. That evening, Millicent told me her aunt’s algorithm was flashing a buy signal with an expected profit of 27% at exactly 9:35 p.m., and that we should both make an investment at that time, me in my demo account and Millicent in her real one.

I told her I was happy to make a demo account trade alongside her, but reiterated that I didn’t want to make any live trades given my role as a crypto journalist. For the first time, she expressed frustration with me. “Oh my gosh, we are not violating anything ethically by trading cryptocurrencies,” she responded before directing me to go ahead and enter the indicated trade—a futures bet on bitcoin’s price going up, for a duration of 60 seconds—in my demo account. I dutifully did so and sure enough, the records showed that I had earned 27%, or just under $21,500, on my investment.

“Because my aunt’s trading information has always been accurate, I have never suffered a loss because of it 🤭,” she said proudly. I asked Millicent how much she had made on the trade, and she sent a screenshot showing a profit of $54,000 now in USDT. I asked how she planned to spend her earnings, and she responded, wondering what I thought she should do with them. “Go on a fun trip somewhere with your knight 😂,” I teased, to which she replied “Haha, if you also make real money, maybe you can use your profits to buy a gift for me before we travel 🤭”

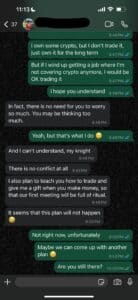

Then she got serious: “Why [might you] have ethical issues trading cryptocurrencies?” Now it was my turn to get frustrated, explaining for the umpteenth time my reservations about actively trading crypto while covering it as a journalist. To placate her, I told her that if I ever took a job that didn’t involve crypto, I would be OK trading it alongside her.

“In fact, there is no need for you to worry so much. You may be thinking too much,” she replied. I agreed that that was possible, but it was how I felt now. And then after stressing that there was no potential conflict, she sent the bombshell message that finally made me realize what I had become entangled in.

“I also [planned] to teach you how to trade and give me a gift when you make money, so that our first meeting will be full of ritual,” she wrote. It was the first time in almost five weeks of daily messaging that Millicent had ever mentioned me spending money on her. “It seems that this plan will not happen 🤣,” she continued.

“Not right now, unfortunately,” I replied. Reeling over the knowledge that the woman I had grown so close to over the course of the previous month and change had been trying to scam me, I waited a few minutes for her to respond. “Maybe we can come up with another plan 😉,” I finally wrote.

I continued to wait, getting up and pacing back and forth in my apartment to try to regain my bearings. After ten minutes of no reply, I tapped out: “Are you still there?” But she never responded, and the blue read check marks never appeared under my message. More than a year later, they still have yet to show up.

The Aftermath

The next morning, I woke up and checked my phone for a response. Seeing none, I began trying to process what had just happened. I texted my best friend to recount what had happened, and he did his best to console me, flabbergasted as I was that anyone could invest so much time and energy in a scheme like this, and carry it out with such sophistication.

While I knew for sure that I had been the target of a scam, a morbid curiosity—and perhaps lingering hope—kept me checking my WhatsApp chat with Millicent several times that day and the next. But of course, she—or whoever had chatted with me daily for more than a month—never did.

Eventually, I noticed Millicent’s Instagram profile had been deleted, although I was still able to access our chat history. Instead of showing her profile picture and name, however, our chat now featured a blank circle where her photo had been and the label “Instagram user.”

Later, when I decided to write about my experiences, I described to GA-SO’s Gochenour, who himself had been a victim of pig butchering, how Millicent had approached me and gained my confidence, and it all sounded completely familiar to him.

As I started to tell him the excuse Millicent had given me for why she didn’t like to video chat, Gochenour stopped me before I could finish my sentence: “I bet I know. She said ‘I was chatting with so-and-so, they were in an accident, and now I’m scared of cameras,’ right?”

Read the related article: 8 Ways to Protect Yourself From Being Victimized by a Pig Butchering Scam