The Trump administration is pulling funding to San Diego researchers exploring issues from HIV prevention to violence against pregnant women, and local scientists warn the impacts will extend far beyond simply ending current projects.

They say the cuts will cost students future jobs and training opportunities, stunting the country’s pipeline of future scientists, and that the administration’s targeting of diversity programs and research will make the scientific workforce less diverse.

Some scientists say they even feel pressured to censor or distort known scientific facts in their grant applications, for fear of being denied funding because the applications relate to topics the Trump administration has sought to defund.

Trump has said the federal government “spends too much money on programs, contracts, and grants that do not promote the interests of the American people,” as he wrote in a Feb. 18 memo.

The National Institutes of Health, where many of the research cuts are concentrated, did not answer questions about what kinds of grants the NIH is cutting and why or about scientists’ concerns about the impacts of the cuts.

But funding termination letters from the agency indicate it is cutting projects it believes deal with topics such as diversity, equity and gender that agency leaders consider unscientific and unrelated to Americans’ health.

The San Diego Union-Tribune interviewed several local researchers who recently learned their grant funding was cut, or who are anticipating cuts based on the topics they research or the programs from which they derive funding.

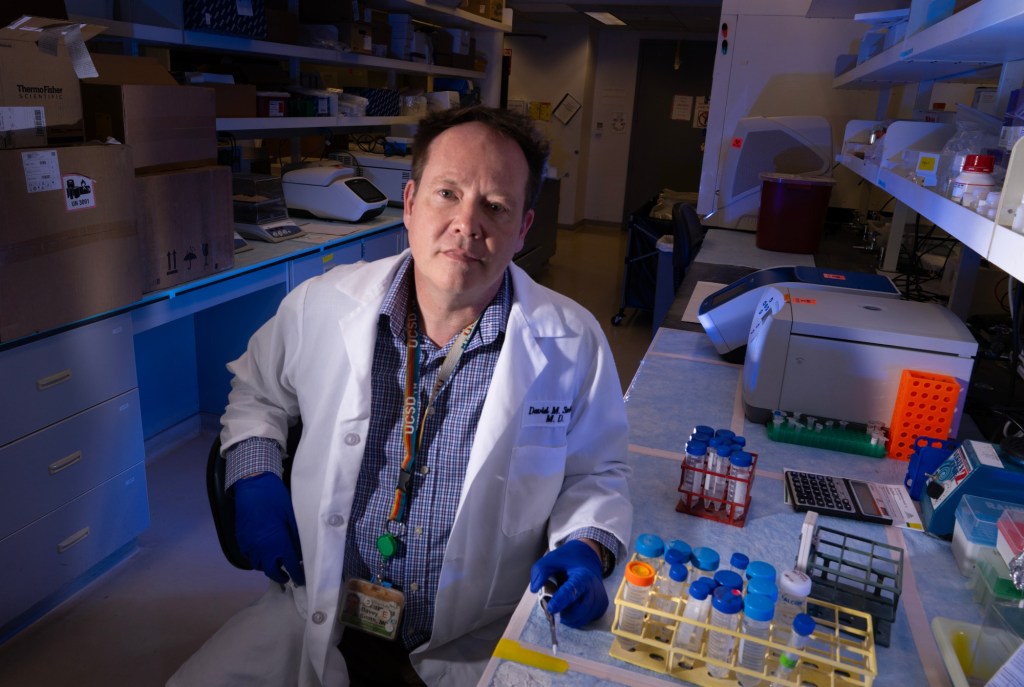

One major cut hit UC San Diego on Thursday when the Trump administration ordered Dr. Davey Smith, director of infectious diseases, to pause or limit work on 16 clinical trials focused on HIV/AIDS, including long-term efforts to develop a vaccine against HIV infection.

Smith said that work collectively represents about $2.5 million in annual NIH funding, and the disruption includes one genomic program that’s involved hundreds of participants dating back more than 15 years.

In addition, at least three other NIH-funded projects at local universities have been terminated, according to a list published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Those include a study at UC San Diego investigating effects of testosterone replacement therapy for transgender men, one at San Diego State investigating mental health impacts from sexual minority stigma and another study at UCSD into how intersectional stigma toward Latino men who have sex with men affects their use of HIV testing and prevention.

‘A difficult day’

March 21 brought bad news and worse news for Keith Horvath.

The NIH axed funding for a three-year study about HIV prevention that the San Diego State psychology professor was co-leading with UC San Diego professor of medicine Susan Little.

Their goal was to investigate how to get more people at risk of contracting HIV to take pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a highly effective HIV preventive drug regimen. They developed a mobile app that provides patients with information about PrEP, and their study is investigating whether trial participants who used it were more likely to take and follow through with PrEP than participants who didn’t have the app.

But with just three months left in the study, now Horvath and Little have lost their funding.

If that weren’t enough, Horvath also learned that same Friday that a decades-old national research network he is involved in also was axed by the Trump administration.

The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV Interventions, which began in 2001, is the only research network in the U.S. that focuses on HIV among young people ages 13 to 24, Horvath says.

“Sadly, that really ended 24 years of scientific progress for young people in terms of HIV,” he said. “As you can imagine, Friday was a difficult day.”

These losses are just two of several federal grants focused on HIV research and prevention that the Trump administration has recently targeted.

The loss of Horvath and Little’s funding will not only hurt the researchers conducting the study, they say, but also the 116 patients participating in their clinical trial. Some patients are still in the middle of completing their PrEP regimen.

“These are individuals who are seeking the best health care and the best opportunities they can get, and they viewed this study as one way of fulfilling that,” Little said.

If not all of the participants finish the trial, it will compromise the study’s nearly three years of work and what can be learned from it, Horvath said. Horvath and Little are looking for alternative private funding and considering writing an appeal letter to the NIH.

Their award was terminated because the NIH decided that their project “no longer effectuates agency priorities,” the NIH told them.

“Research programs based on gender identity are often unscientific, have little identifiable return on investment, and do nothing to enhance the health of many Americans,” an NIH official wrote in the termination letter. “Many such studies ignore, rather than seriously examine, biological realities. It is the policy of NIH not to prioritize these research programs.”

Horvath and Little’s study is not about gender identity. Horvath speculates that their funding was flagged for termination because men who have sex with men, as well as transgender women, are highly impacted and at risk for HIV.

“Because we were following the science of who is at highest risk of HIV, it seems to be that’s why it was defunded,” Horvath said.

But he added, “Our decision to enroll members of those communities isn’t based on a political agenda at all. It’s based off of sound scientific evidence of which Americans are at highest need.”

‘It’s not the first time’

Christian Cazares is becoming a neuroscientist so he can help people like him become scientists, too.

A naturalized U.S. citizen who immigrated from Mexico as a youth and is a product of U.S. public education, Cazares is now a neuroscience postdoctoral researcher at UCSD.

“I want to be a research professor to not only do cool science, but to help diversify the workforce by providing mentorship that is a lot more relatable to people of low-income means or Latinos,” he said.

His work focuses on studying brain activity in children with autism spectrum disorder and investigating whether anything gets missed when scientists use animals, such as mice, to model such brain activity.

Cazares’ postdoctoral career is funded by a NIH fellowship called D-SPAN, which has provided up to six years of funding for promising neuroscience graduate students from underrepresented backgrounds nationwide. The fellowship has helped develop more than 200 neuroscientists since 2017, according to the NIH, many of them women and people of color.

Trump has targeted federal programs like D-SPAN that are focused on diversity and equity because he says such programs discriminate based on race and sex and contradict American values of individual merit and hard work.

Cazares is in the second year of what is supposed to be a four-year grant through D-SPAN. He said this month he has not yet been told officially whether D-SPAN is canceled or whether his fellowship funding — his salary — will be terminated.

Since early February, the NIH has changed references to the D-SPAN program on its website from the present tense to the past tense, scrubbed the word “diversity” from the program webpage and the program is no longer accepting applications.

Cazares worries that the end of funding for diversity and equity programs will mean fewer low-income people of color will become scientists, and will ultimately set back research efforts to solve problems facing those communities.

Whatever happens, Cazares has no plans to leave science. He is looking for alternative funding as a backup.

“It’s basically a matter of adapting and recognizing it’s not the first time in history that people like us have been excluded from science,” Cazares said. “We just have to do what we can in the meantime and hold the line until we can make a better future for the next generation of scientists, once things hopefully change.”

‘We have to just keep trying’

Nowadays, Brenda Bloodgood talks to students almost daily who say they don’t know why they’re trying to become a scientist right now.

“I often don’t know what to tell them, except we have to just keep trying and hope that this turns around,” the UCSD associate professor of neurobiology said.

As the director of UCSD’s neuroscience graduate student program, Bloodgood said she is now seeing labs losing their funding, which means they are no longer able to pay for the undergraduate or graduate students they employ. As a result, first-year students are struggling to find a lab that is able to take them — a requirement for their training.

Already, the neuroscience graduate program has decided to shrink its incoming cohort size from 18 students to no more than 12, Bloodgood said. Similar reductions are happening at graduate programs across the country.

Bloodgood is also the co-director of UCSD’s STARTneuro, a NIH-funded program that provided training, mentorship and funding for 10 community college transfer students each year to help them enter neuroscience research. The program’s NIH funding expired this year – and Bloodgood’s team has applied for a renewal — but the program’s future is unclear as federal officials have targeted programs that similarly support underrepresented students.

“It had been entirely designed to provide training and mentorship opportunities to students that had not had those opportunities,” Bloodgood said.

The effects of the ongoing cuts go beyond the immediate impact of ending current research, Bloodgood stressed — it also means that universities will train and produce fewer future scientists.

It’s a brain drain problem that will have ripple effects years into the future, Bloodgood said, noting that it takes a decade to train a neuroscientist. Meanwhile, other countries see an opportunity to gain and cultivate research talent; many European officials have said they plan to recruit fleeing American scientists.

“We’re going to have a significant contraction of the scientific workforce,” Bloodgood said. “This will be felt in academia for obvious reasons, but this will also be felt in biotech, in pharmaceutical companies — the biomedical industry writ large.”

‘If I can’t try out things, I can’t tell you how to fix it’

Homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women and recently pregnant women in the U.S., but relatively little research has been conducted on why that is or how to prevent it, said Rebecca Fielding-Miller, associate professor of public health at UCSD.

Fielding-Miller was part of a team of researchers on a grant project that would have focused on the role of intimate partner violence in mortality for these women.

The team was going to train a dozen early-career scientists and clinicians to conduct their own research on the issue. Each of them would have received a yearlong mentorship and produced a research paper. And the researchers were going to write an open-source curriculum on how to train others to conduct similar research.

The NIH axed the project’s $400,000, two-year grant on March 21. The team had not yet recruited any participants.

The NIH stated its reasons in its termination letter for the project.

“Research programs based primarily on artificial and non-scientific categories, including amorphous equity objectives, are antithetical to the scientific inquiry, do nothing to expand our knowledge of living systems, provide low returns on investment, and ultimately do not enhance health, lengthen life, or reduce illness,” it said.

Fielding-Miller found the letter insulting — particularly its suggestion that fostering research into deadly violence against pregnant and recently pregnant women would “not enhance health, lengthen life or reduce illness.” She noted that pregnancy is associated with a significantly higher risk of homicide for Black women and younger women.

Fielding-Miller said the administration’s decisions to target research based on its mention of terms and issues it opposes — such as women, gender and ethnicity — means public health realities that affect or disproportionately affect various communities will go unexplored and ignored.

“If we don’t measure a problem, we can’t tell you it exists. If I can’t use the words to describe the problem, I can’t tell you it exists. If I can’t try out things, I can’t tell you how to fix it,” Fielding-Miller said.

Staff writer Gary Robbins contributed to this report.

Originally Published: