In the back corner of a bus, a woman pulled out a script.

The edges had curled and yellowed and some of the text was circled in pen. She set the paper in her lap and scanned the words, lips moving silently.

The delivery needed to be right.

She wore bright green earrings. Her braids were black, yellow and blue. Both swayed as the driver rumbled through downtown San Diego.

Sometimes on rides like these she would tell fellow passengers about her destination, and how much the place meant, but on the last Friday in January the woman was so focused she barely looked out a window to see the doorways where she’d once slept.

Here’s the pitch: It’s an original musical about homelessness in San Diego created by and starring people who’ve spent years in local encampments.

Voices Of Our City Choir, which gained national attention a while back from an appearance on America’s Got Talent, is running the show with La Jolla Playhouse and San Diego’s Moxie Theatre.

There is precedent. The London-based theater company Cardboard Citizens has long worked with people on the street, as has the Los Angeles Poverty Department, a performance group made up of homeless residents.

Yet similar collaborations remain rare, and representatives of theater organizations in Southern California and New York City said this appeared to be the first such effort in San Diego. Early performances may begin as soon as April.

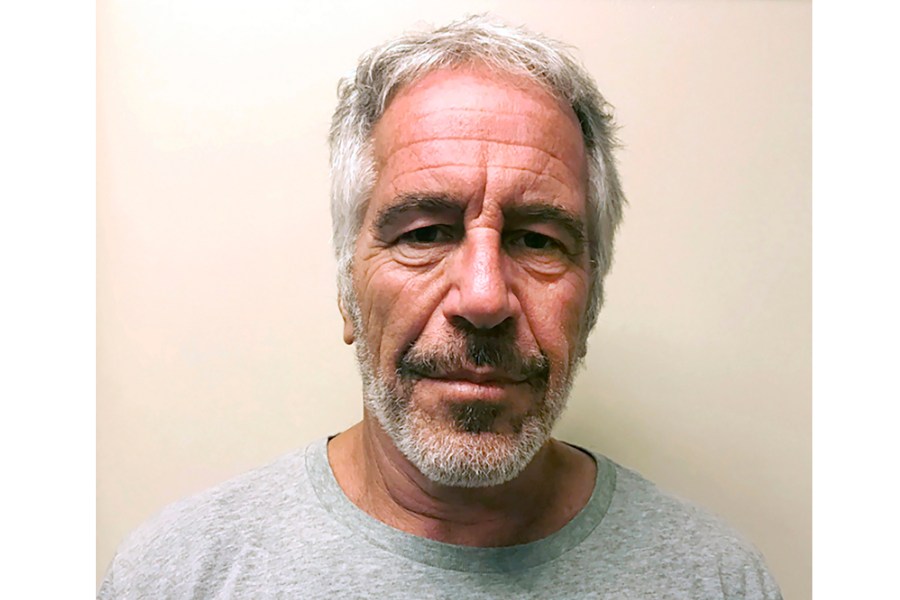

Raven Jones, 66, rides on a bus from her downtown San Diego apartment to St. Paul’s Cathedral on Jan. 26.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Raven Jones, the woman on the bus, was headed to the first rehearsal of the new year.

She looked up from her script.

“Oh!”

She pulled a yellow cord. The driver stopped outside St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Jones spent much of her adolescence in Mira Mesa and graduated from Kearny High School. She left home as a teenager amid tensions with her family — Jones is transgender — and passed countless nights on sleeping bags and church cots. The gin and juice didn’t help things. Nor did the cocaine.

A few years ago she relapsed again. Furious with herself, Jones wondered if she deserved to live. Then she happened to hear singing while passing Seaport Village.

It was Voices Of Our City Choir. She joined immediately.

Inside the church, Jones greeted fellow members by a drink cart. COVID-19 infections canceled the last rehearsal and it had been a while since everyone was together.

“Raven,” a woman called from the front. “Brother Juan is out here.”

Jones looked up, distracted. “Who?”

“Juan.”

Others chimed in.

“Juan?”

“Yes.”

“Oh Juan!”

Jones strode back toward the door.

Juan Campbell was part of the group that sang on America’s Got Talent.

In the video from 2020 you can see him standing on risers near the back of the stage. He’s one of the most expressive people up there, all swaying shoulders and bobbing hands. When the song ends and the show’s host hits the Golden Buzzer, dropping confetti and promoting the choir to the next level, Campbell rushes into a group embrace.

“This can’t be real,” he told The San Diego Union-Tribune at the time.

On Oct. 4 of last year, a little after midnight, Campbell was driving through Anaheim to a construction job.

The California Highway Patrol later concluded that his pickup clipped a guardrail. The Chevrolet rolled. Campbell was “ejected” onto Interstate 5 and “collided with the ice plant embankment,” according to the crash report. An officer summarized his injuries: “Laceration to face.” “Spinal fractures.” Broken leg, collar and rib bones. Collapsed lung.

Campbell hadn’t been to a rehearsal since.

At St. Paul’s he sat in a wheelchair. The backrest featured the words, “Property of Arroyo Vista,” the name of the nursing center where he now lives.

He hoped the next few hours would again make him feel part of the community.

Sixty-year-old Juan Campbell, center, speaks to other members of Voices Of Our City Choir at a rehearsal in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Others arrived. There was white skin and black, gray hair and brown ponytails, eye liner and beards. Metal chairs were arranged in a circle within the main sanctuary, and Jones took a seat by a wood pillar. Campbell parked near a piano.

“It is so nice to see everyone’s faces again,” said a woman in a Blink 182 T-shirt. “We’re going back to basics today.”

The Blink fan was Desireé Clarke Miller, the show’s director and co-writer as well as the top artistic director at Moxie Theatre, which will eventually host the musical.

Miller asked everyone to reflect on the past year and name their hopes for 2024. Several said they’d always dreamed of performing professionally.

When it was Campbell’s turn, the room stilled.

“Something that I did last year that I’ve never done before is I’ve never —.” He paused. Campbell’s left hand gripped part of his wheelchair, clenching and unclenching the metal. “I’ve never taken life the way it has been handed to me.”

The pause in Campbell’s speech was significant to two people across the circle.

One was Miller, the director. The other was a blonde woman in a gray sweater.

Shairi Engle believes writing saved her life.

Decades ago, Engle fled an unstable home in Pennsylvania and ended up with her dad out West, attending Carlsbad High School. She eventually enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, hoping the military might offer stability.

Instead, a sexual assault by a fellow airman led to drinking (first Guinness and gin, then anything and everything) and a deep depression. After her service ended in 2005, Engle found herself homeless in Northern California.

The weather grew colder. She stole a Ford F-150 to have a place to sleep. One day she approached the top of a cliff and considered jumping.

A long list of things, over many years, has kept her from going over that edge, including therapy and PTSD treatment through the VA. But she gives a special nod to a writing program through the La Jolla Playhouse, which also led to a robust career — one of her plays was praised by the actor Adam Driver and the “Angels in America” creator Tony Kushner.

All the while, depression hovers.

Just a year-and-a-half ago, Engle spent two days on the bathroom floor of her home in Chula Vista, unable to rise until her phone rang with an offer: Would she be interested in co-writing a musical?

Desireé Clarke Miller, left, and Shairi Engle, center, lead a rehearsal for a new musical on Jan. 26.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Engle and Miller have since dedicated months to distilling testimony from choir members into one coherent plot. The current draft is a 36-page meta-narrative about members of a choir who find that time stops, literally, when they join together.

In the process, the writers have become focused on pauses between words.

Was it possible to create a world on stage where audiences could silently fill those gaps with their own hopes and fears? Where silence hit as hard as a song?

The script is still a work in progress, and the discussion Friday turned to a brief moment when a character describes seeing a speeding car run over a family of ducks.

“So the ducks just get killed?” a member asked.

“Except for the mom,” Miller said.

The member didn’t like it. “Maybe you could also — someone could find a baby duck that didn’t get killed and nurse it back to life?”

The writers looked at each other. The anecdote was based on a real event by Balboa Park, and the man who’d witnessed it was infuriated that the reckless driver appeared to escape scot-free while those without homes could be arrested for sleeping in tents.

“When we have challenging ideas that are heartbreaking,” Engle said, “we might want to immediately solve it.” But resurrecting a duck seemed wrong. “I want to leave space for unresolved, messy aspects.”

The back and forth continued for so long that another woman, looking bewildered, finally spoke up from the side.

“I’ve been gone — so is this play about ducks?”

Soon it was time to perform.

The writers wanted to get everyone comfortable again before a crowd, so the script was set aside for an improvisation game. Small groups would act out scenes using only gibberish — English wasn’t allowed — to see who could communicate with just body language and tone. This meant Jones wouldn’t have to worry about specific words.

She still needed to deliver.

Four members chose to stage a birth with Jones as a supportive friend. During practice, the “pregnant” woman huffed and howled while Jones leaned in muttering nonsense (“Na na na na na na na”) and made soothing motions with her hands.

The woman was having none of it. Jones fell back in a chair, laughing. The group tried a second time. Jones couldn’t keep a straight face.

“Who wants to go first?” Miller asked.

Jones’ group stepped up. The room quieted.

Contractions began fast: “Boo boo boo boo boo boo!” Jones swept in. “Na na na na na na!” The woman waved her away.

This time, Jones didn’t back down. Nor did she break character. Jones stayed by the woman’s side until everyone was admiring a healthy, if invisible, newborn baby. The crowd applauded.

Miller stood for a debrief. “There was one issue I saw with this.”

The director pointed out that Jones had spent part of the performance with her back to the crowd. “You should be able to feel: ‘I can’t see anyone in the audience,’” Miller said. Jones nodded.

A few scenes later it was Campbell’s turn.

Campbell and another member sat facing a third man, whose straight back and rigid face made him look like a banker — which was apt since the scene appeared to be two men asking for a loan.

Campbell interpreted the “don’t speak English” rule somewhat narrowly and began shouting words in Spanish. “Dos, dos!” he exclaimed. “Mucho mucho!” The banker waived away their request. Campbell flipped him off.

The audience roared. People were sucking air, struggling to stay in their chairs.

Campbell beamed.

About a week after that rehearsal, a member of the musical died. She was the group’s second death in four months.

Each was unexpected. Many details remain unknown.

Christopher Edmonds died in October, and the group plans to keep his voice in the show by playing a recording of comments he once made to the San Diego City Council about the camping ban.

It’s unclear how the more recent loss of Lisa “Leace” Taylor will affect the show. Members are still reeling.

The playwrights do plan to re-work the script.

Miller will likely write at her desk in Moxie Theatre. Engle had wanted to type new scenes on her Chromebook, but the tablet was inside a car that flooded during last month’s storm. The choir gave her an HP laptop instead.

She likes to work outside, away from her house and that bathroom floor. One tree in Balboa Park has roots large enough to nestle against. Engle can sit by herself and fill each page with words and silence.