Oscar-winning film director Cameron Crowe was just 15 when he met fellow San Diego native Lester Bangs here in 1973, but he remembers the encounter with his early mentor as if it happened last week.

“Meeting Lester himself, at an interview he was doing at (radio station) KPRI while he was visiting home for the holidays, he struck me like an avuncular uncle,” said Crowe of Bangs, whose seminal writing was celebrated in Jim DeRogatis’ 2000 book, “Let It Blurt — The Life and Times of Lester Bangs, America’s Greatest Rock Critic.”

“He had a black leather jacket, a size too small, a friendly face, a young man’s paunch, an overgrown mustache and a red Guess Who shirt,” Crowe continued. “The mustache and physique reminded me of Meathead (Rob Reiner’s character) in the ‘All in the Family’ (TV series). He gave me some advice but treated me as an equal. He also said: ‘I have to catch the bus back to El Cajon. I’m heading over to see my ex-girlfriend so she can break up with me again’.

Actor Philip Seymour Hoffman portrayed Bangs in Crowe’s acclaimed 2000 film, “Almost Famous,” which in 2019 was transformed into a musical at the Old Globe and opened on Broadway last November. Thursday marks what would have been his 75th birthday.

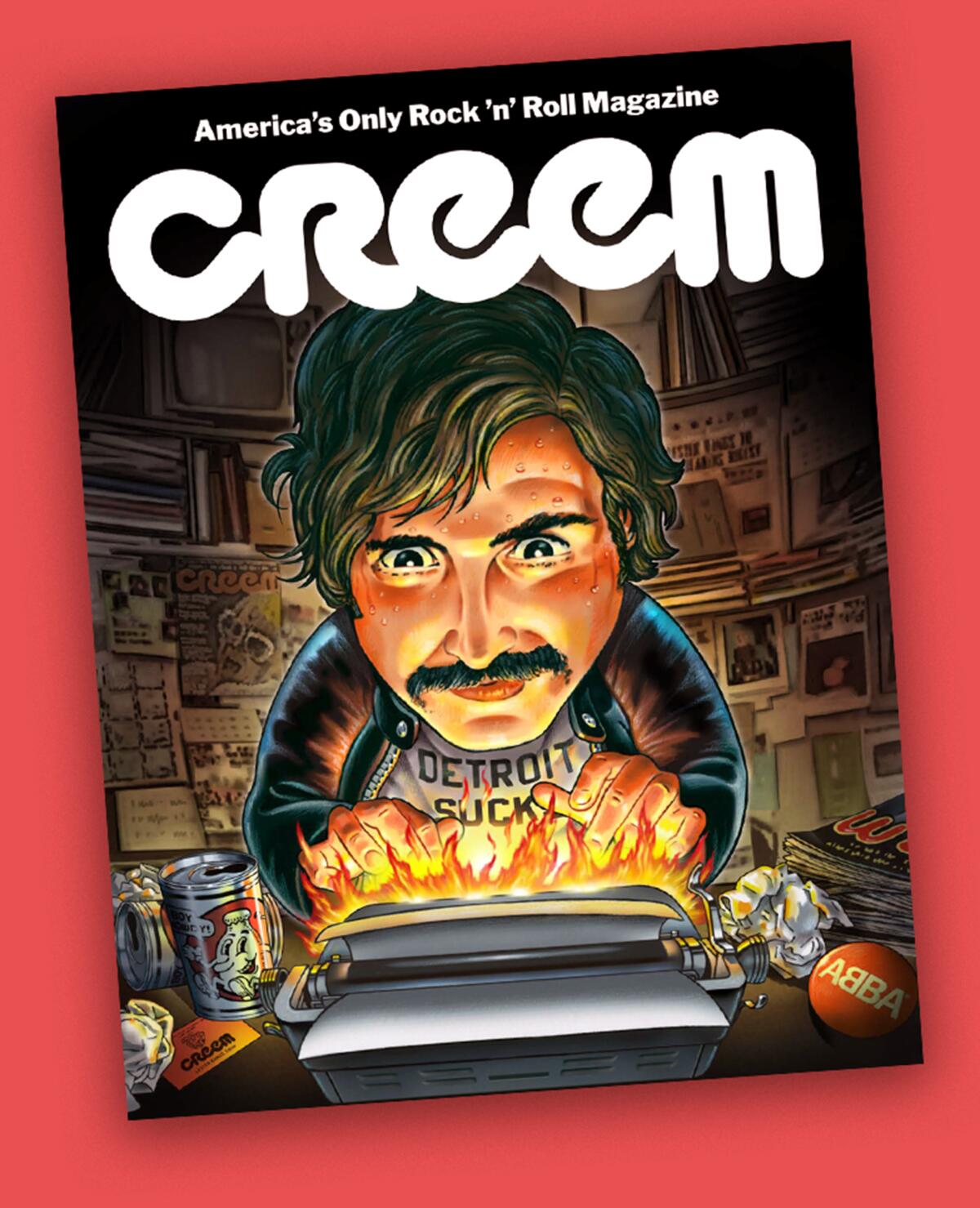

An undated photo of Lester Bangs in the offices of Creem magazine. Bangs died in 1982.

(Courtesy of Charlie Auringer)

Bangs who was born in Escondido, grew up in El Cajon and died in New York in 1982 at the age of 33 from an apparently accidental overdose of Darvon, a prescription drug. His impact has been well documented in various mediums.

The 1981 Ramones’ song “It’s Not My Place (In the 9 to 5 World)” includes the line: Hangin’ out with Lester Bangs. R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe gives Bangs a fond shout-out in the band’s 1987 classic “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” singing: Mountains sit in a line / Leonard Bernstein, Leonid Brezhnev, Lenny Bruce and Lester Bangs.

In 1990, the now-deceased author David Foster Wallace dedicated his first co-written book, “Signifying Rappers,” to Bangs. The mustachioed music critic also inspired Ariel Pink’s 2006 song, “Cuz You’re Dead (Lester Bangs).”

In 2018, Bangs was the subject of the New York Public Theatre production, “How to be a Rock Critic.” It debuted in San Diego in 2015 as part of La Jolla Playhouse’s annual DNA New Work Series.

The foundation for the play is DeRogatis’ seminal Bangs book, the first biography ever written about a rock critic. A veteran music critic and creative writing professor, DeRogatis now uses some of Bangs’ work in his curriculum at Columbia College Chicago.

“The mind boggles, thinking of Lester at age 75, but then we can say the same of Mick Jagger at 80,” DeRogatis said.

“To some extent, our rock ‘n’ roll heroes remain frozen in time at the point when we discovered them. In Lester’s case, it might be the proto-punk of his El Cajon/San Diego days, or the gonzo legend of his Creem (magazine) period in the mid-’70s, or the already older, wiser sage who wrote for The Village Voice in his New York days toward the end, when I began reading every word he wrote.

“I like to think of that Lester, but happier and still with us, using that one-of-a-kind incisive intellect and cutting wit to celebrate or rant against every corner of our complicated culture.”

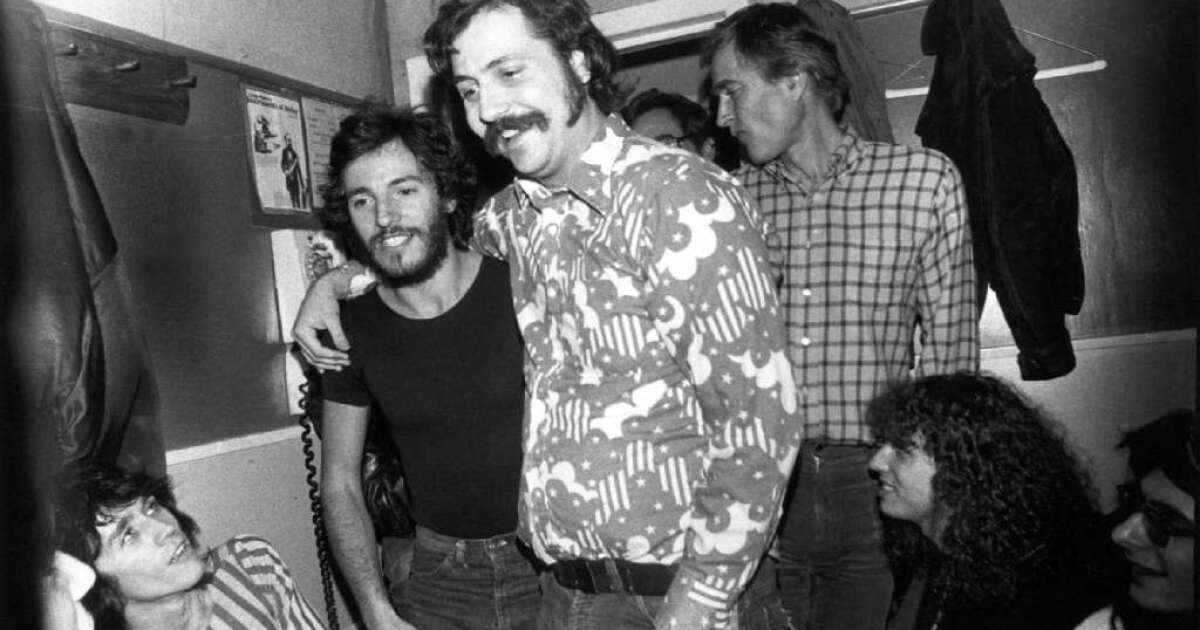

Pioneering San Diego-born rock journalist Lester Bangs, left, is interviewed by WINN Radio’s Brent Alberts at WIIN Radio’s studio on March 24, 1974 in Atlanta.

(Tom Hill / WireImage)

‘Almost scary-brilliant’

Grossmont College English professor Raul Sandelin, a longtime champion of Bangs’ work, wrote, produced and directed the 2013 film documentary “A Box Full of Rocks: The El Cajon Years of Lester Bangs.” For more than a decade he hosted the annual Lester Bangs Memorial Reading events at Grossmont College, which in 2019 featured DeRogatis as a special guest. Bangs was a Grossmont student between 1966 and 1968.

The 1987 book, “Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung: The Work of a Legendary Critic: Rock ‘n’ Roll as Literature and Literature as Rock ‘n’ Roll,” features dozens of articles that Bangs wrote for an array of publications, including Rolling Stone, Creem and The Village Voice. One chapter alone includes 15 articles Bangs penned for Creem.

After being dormant for years, Creem was reborn in 2022 as a subscription-only print and online magazine. “Psychotic Reactions” was edited by Greil Marcus, an esteemed music author who — like Bangs — is a former writer for Rolling Stone. It was followed in 2003 by “Mainlines, Blood Feasts & Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader,” which was compiled by another Rolling Stone and Creem alum, John Morthland.

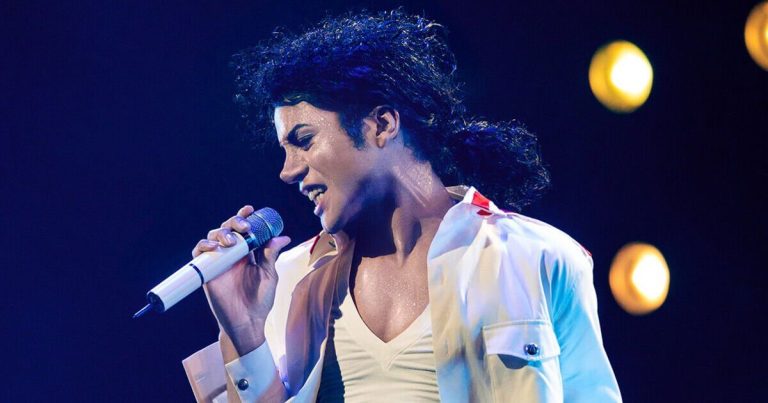

The cover of the new issue of Creem magazine, featuring Lester Bangs.

(Shorefire Media and Creem)

The most recent homage to Bangs is the new issue of Creem, for which Bangs worked as an editor and critic from 1971 to 1976. He is the issue’s sole cover subject. Forty-six of its 109 pages are devoted to him and his work, as befits a voracious writer who could expound on garage-rock, heavy-metal, punk, jazz and more with equal skill and wit, insight and irreverence.

“On the page, his writing presence could be powerfully sharp and almost almost scary-brilliant,” said Crowe, who as a teen succeeded Bangs as the music critic for the underground newspaper San Diego Door. Black Sabbath and John Coltrane. The Stooges and James Taylor. Van Morrison and Kraftwerk. Lou Reed and Otis Rush. Ray Charles and Jethro Tull. Sun Ra and Cheech & Chong. Captain Beefheart and The Carpenters. Bob Dylan and Kiss. Patti Smith and The Captain & Tennille. Deep Purple and The Mekons. Miles Davis and The Shaggs. John McLaughlin and Foghat.

Bangs wrote memorably about them all, including a series of confrontational interviews with Lou Reed that soon became the stuff of legend. His 1975 interview with Reed for England’s NME began: “Lou Reed is a completely depraved pervert and pathetic death dwarf — a wasted talent living off the dumbbell nihilism of a ‘70s generation ….”

Bangs’ 1977 review of the album “The Beach Boys Love You” took a far different tack, beginning: “The Beach Boys present the most convincing argument in our entire culture for never growing up.” His review the same year of Ted Nugent’s “Free For All” album kicked off by invoking the words of Ugandan dictator Idi Amin.

Cameron Crowe poses outside the the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre in New York on Oct. 27, 2022. Crowe adapted his autobiographical coming-of-age film, “Almost Famous,” into a Broadway stage musical. Both the film and the musical feature an actor in the role of music critic Lester Bangs, who was a key early mentor of Crowe’s.

(Emilio Madrid / Associated Press)

“Music was the only thing Lester cared about,” said Creem Editorial Director Jaan Uhelszki, a Palm Desert resident. She began working at the magazine, then headquartered 90 miles from Detroit, on the same day in 1971 that Bangs began his tenure as editor. Her desk was next to his. Like Crowe, she credits Bangs as a pivotal mentor for her and other young writers.

“He was convinced the secret of the universe was encoded in songs and that rock stars were prophets who had something to say,” Uhelszki said. “I’ve never been around anyone so dedicated to the sound and wanting to find the truth in music and lyrics. That is how he was wired and everything else fell by the wayside.

“Lester and Cameron both had the same drive. They were both savants, the smartest kids in the class. Lester was unruly and passionate about music. And Cameron is very controlled and almost by-the-book passionate about music.”

She chuckled.

“Lester had big gestures and outbursts,” Uhelszki elaborated. “If he hated or loved something, you knew it. Cameron kept it all inside and put it on the page. Both of them were great hangs and musicians loved being around them. Cameron was like Steve Martin, making very subtle wisecracks. Lester walked in a room and changed the air — fun was going to be had!”

Crowe agreed.

“Lester was just so entertaining,” he said.

“I remember getting my first copy of Creem from a kindly stoner at the front desk of The Trip, a head shop next to the Spreckels Theatre (in downtown San Diego). He let me purchase it from the 18-and-over rack of reading material. Rolling Stone was then an ‘adult’ publication too…

“Lester’s writing was unlike some of the stuffier record reviews I’d read in mainstream publications. I loved Robert Hilburn for the precision of his reviews in the Los Angeles Times and was addicted to Lester for his humor and his danger. He was reckless, and alive, and his banter had sound and fury in it. It read like music. And he was from San Diego!”

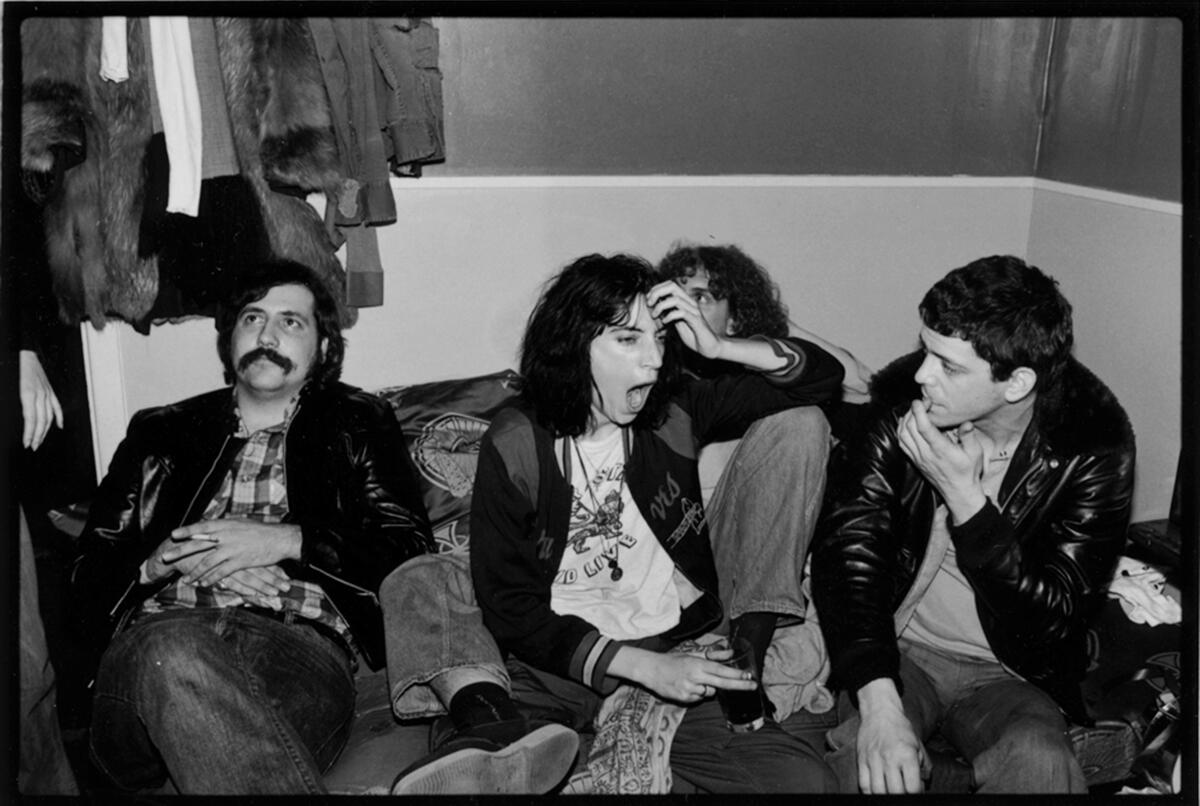

Lester Bangs, Patti Smith, and Lou Reed are shown at The Bottom Line in New York City in 1975. Bangs’ interviews with Reed were famously combative.

(Kate Simon)

Gym-class renegade

Bangs was raised by a mother who was a devout Jehovah’s Witness. Not remotely religious, he soon developed a lifelong passion for music and writing.

Jerry Raney and Jack Butler, long among San Diego’s most respected and accomplished rock musicians, befriended Bangs when all three were in junior high in El Cajon. Bangs would sometimes sit in on harmonica with Raney and Butler’s high school rock band, Thee Dark Ages. Raney and Butler perform Dec. 20 in La Mesa at Hooley’s Public House, where they’ll play several songs they wrote in honor of Bangs.

Both musicians describe the teen-aged Bangs as “brilliant,” “very intellectual,” “really cool” and “smarter than anyone else” they knew. He shared their love for such British Invasion bands as the Rolling Stones and Yardbirds, although Bangs soon also embraced such jazz giants as Coltrane and Davis.

He convinced Raney to pay attention to the early Jeff Beck’s innovative guitar playing. And he turned Butler into an avid fan of Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band, after insisting Butler listen to the group’s classic, room-clearing 1969 double-album, “Trout Mask Replica,” in its entirety, on headphones.

But the first written work by Bangs that Raney and Butler cite had nothing to do with music. Rather, it was a full hand-scrawled notebook Bangs filled to make up for repeatedly missing his and Raney’s gym class at El Cajon Valley High School.

“Lester wasn’t really into sports and he wouldn’t put on shorts for gym class or participate,” said Raney, who rose to prominence playing guitar and singing in the San Diego bands Glory — which also featured Butler — and the Beat Farmers.

“If you missed class. you lost 10 points for the day. And to make it up, you’d have to write a paper on sports and you’d get a point back per page. Lester kept writing and writing all this stuff. When he turned it in to Coach Foster, it looked pretty much like a book! It was called: ‘Hector, The Homosexual Monkey’.”

“It was one of the funniest things ever!” Butler said. “And it got Lester kicked out of gym class and into study hall, so he kind of won that battle. I don’t think he ever said: ‘I want to be a writer.’ But he didn’t have to, because it was clear to everyone that’s what he would do. He started writing for Rolling Stone, mailing in album reviews to them, and we thought it was the coolest thing.”

Lester Bangs, right, is shown with Danny Fields, left, photographer Roberta Bailey and singer Debbie Harry outside the Bottom Line in New York on June 24, 1977. They were waiting to attend a concert by Roxy Music singer Bryan Ferry.

(Allan Tannenbaum / Getty Images)

‘Sloppiest human on earth!’

As can be expected when reflecting on someone who died more than 40 years ago, not everyone who knew Bangs has the same recollections of him.

Uhelszki, Creem’s editorial director, thought Bangs would follow his heart, become a great novelist, get married and live a long life. She was stunned when Crowe phoned in 1982 to inform her of Bangs’ death.

Raney and Butler did not see Bangs as the marrying kind. Neither were surprised that he only lived to be 33.

“Lester burned the candle at both ends,” Raney said. “He was quite the partier.”

But Uhelszki, Raney and Butler readily agree Bangs’ reputation for being uber messy was well-earned.

“His mom’s house was immaculate, but I’d never seen anything like Lester’s room,” Raney said. “It was so messy you could barely walk into it!”

“He was the sloppiest human on earth!” said Butler, one of Bangs’ college roommates. “But we were all slobs then and none of us had any money.”

“Oh, my god, Lester was the messiest person ever!” Uhelszki fondly recalled.

“I sat next to him at Creem for six years, for better or worse, and his desk was covered with banana peels, Taco Bell wrappers, old socks, stacks of press releases. He had a hermit crab, which he loved, in his bathtub — meaning he didn’t take baths or showers himself.

“But he was a really prolific writer and a true professional, even though he dropped out of Grossmont and didn’t have any editorial or journalistic training. He knew so much more than I did.”

What legacy does Bangs leave for today’s aspiring young writers?

Crowe, his former protégé, offers a knowing response.

“Write your heart, write your rage, write your passion,” Crowe said. “Help the next generation if they ask you for advice.”