The law that came into play when a murder charge was recently dropped against an Oceanside woman was part of a high-profile package of abortion and reproductive health protections signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last year.

The bill was drafted to keep women from being prosecuted because of their actions while pregnant.

That legislation, like the related laws, followed the Supreme Court’s ruling overturning the half-century-old constitutional protection for abortion under Roe v. Wade — and the subsequent increase in abortion bans and restrictions in Republican states.

The bill was introduced after two women in Kings County were charged with murder following the delivery of stillborn babies. There were some similarities between their cases and the one against Kelsey Shande Carpenter of Oceanside. All three women used drugs during their pregnancies.

There was one very big difference. Carpenter’s baby died shortly after birth. Instead of facing a murder charge, Carpenter pleaded guilty to one count of child endangerment.

The cases in Kings County spurred California Attorney General Rob Bonta to issue a statewide alert to law enforcement not to prosecute women who miscarry or have a stillbirth, according to CalMatters.

Assembly Bill 2223 was introduced by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, D-Oakland, to clarify existing law. The measure prohibits the prosecution of women for decisions that affect their pregnancies, including a self-induced abortion or one that happens outside the medical system.

The bill also does away with the requirement that coroners investigate stillbirths.

Carpenter’s attorneys referred to the new law and asked to have the murder charge dismissed, arguing the case was based on protected actions and decisions, and that it violated her right to choose to have an unattended home birth, according to Teri Figueroa of The San Diego Union-Tribune.

An appellate court ruled Carpenter could not be prosecuted for decisions that may have affected her pregnancy, but said she could be charged for actions taken after the baby was born.

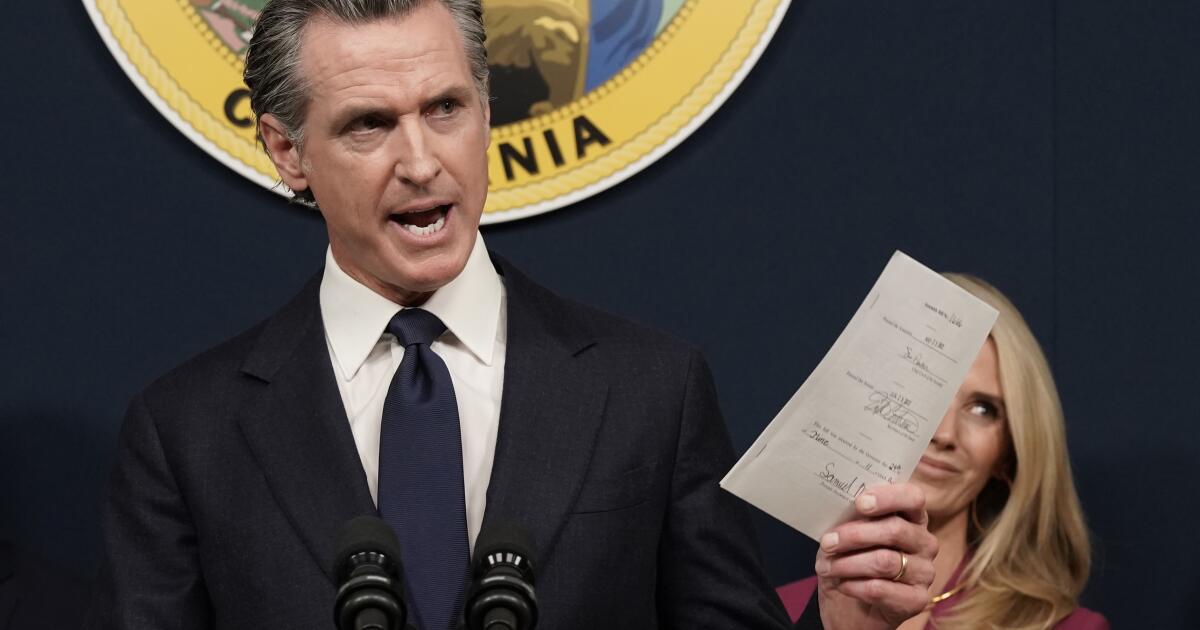

AB 2223 was one of 13 bills regarding reproductive health passed by the Democratic Legislature and signed by Newsom in September 2022. In addition to prohibiting prosecutions and civil lawsuits under certain circumstances, the laws aim to improve access to reproductive care, bolster the state’s abortion clinics, strengthen privacy safeguards and provide travel funds for low-income individuals seeking abortions.

The Wicks bill received strong support from the Legislature, but faced loud public opposition. The measure drew protests outside the state Capitol, with some opponents claiming it would legalize infanticide and allow babies to be killed up to four weeks after birth — something Wicks and other supporters strongly denied.

The Sacramento Bee and Reuters fact-checked stories on the infanticide claims and found them to be false.

Part of the issue stemmed from language in the bill about “perinatal deaths.” Perinatal is generally defined as the period immediately before and after birth.

Wicks amended the bill to make clear a woman will not be investigated or charged for experiencing a miscarriage, stillbirth, abortion, or “perinatal death due to causes that occurred in utero.”

After that change, the California Catholic Conference removed its opposition to AB 2223 and took a neutral position.

In a statement after the governor signed the bill, Wicks said, “(t)oday, we cement this right for millions of Californians, ensuring that no one will ever again face the trauma of having their pregnancy policed by state systems.”

In the Oceanside and Kings County cases, the women did not appear to be trying to end their pregnancies. The birth and stillbirths came at or very close to full term.

All had used methamphetamine during pregnancy.

In one of the Kings County cases, the woman pleaded no contest to voluntary manslaughter and the murder charge was dismissed. A judge then overturned Adora Perez’s conviction and 11-year sentence, ruling the state’s voluntary manslaughter law doesn’t apply to the unborn.

The murder charge was reinstated to allow Perez to argue against it, according to KTVU in San Francisco. The charge was eventually dropped. Perez already had spent four years in prison.

Last year, a judge dismissed a murder charge against Chelsea Becker, who had been the subject of a police search and was arrested two months after her baby was stillborn, according to The Guardian. Becker spent more than a year behind bars.

Attorney General Bonta issued a legal interpretation in January 2022 that said the fetal murder law was only intended to criminalize violence against pregnant women that caused fetal death — not the actions of pregnant women themselves. That was before the Wicks bill clarified the law.

Unlike Carpenter, the other two women had gone to hospitals. Authorities had removed Carpenter’s two sons from her care after each tested positive for drugs at birth, and she feared they would take this baby as well, according to court documents.

Carpenter, who gave birth alone at home, was initially charged with second-degree murder. After prosecutors dropped that charge, Carpenter pleaded guilty to a single count of child endangerment and an allegation that it caused death.

But the focus turned to her actions after the birth rather than during pregnancy, according to the Union-Tribune’s Figueroa.

Carpenter cut the umbilical cord herself, was unable to stop the baby’s bleeding and didn’t seek medical assistance, court records said. She said her phone was dead and she had misplaced the charger.

If convicted of second-degree murder, Carpenter could have faced a sentence of 15 years to life. Instead, she was sentenced to two years in prison.

All of these were tragic incidents involving some very bad decisions. But it’s hard to see under these circumstances what sentencing a woman to a lengthy prison term would accomplish.

With the comparatively short incarceration, and hopefully with some help, Carpenter may have a chance at redemption and a better life.