It’s probably dreaming to think major immigration and border legislation has a chance of getting through Congress.

That hasn’t happened for decades and, with political polarization seemingly as severe as ever, movement is less likely now.

But let’s head out on what may appear to be a fool’s errand anyway and give it some consideration because there’s actually a confluence of dynamics that could lead to an agreement.

That’s not to say what might emerge would be the right thing to do.

The recent Senate Republican proposal, mirroring a GOP House bill in the spring, is entirely focused on border security and enforcement — two very important matters.

What the country really needs, and has for a generation or more, is also very important: a comprehensive plan that deals with all elements of the country’s broken immigration system, including a path to citizenship in addition to enforcement. That’s President Joe Biden’s preferred approach.

That definitely isn’t going to happen at this time.

Republicans appear to have considerable leverage, in part because they’ve tied the proposal, rightly or wrongly, to aid for Ukraine in its ongoing battle to fend off Russia’s invasion. That aid package is a high priority for Biden, though not so much for many Republicans, particularly in the House.

Meanwhile, political necessity may motivate Democrats to be more flexible, if they can get some concessions. Key among their priorities is a permanent resolution for younger undocumented immigrants in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program who have been in legal limbo for years.

In nationwide public opinion polls, Biden and Democrats are getting killed on immigration. Even in deep blue California they are in trouble on the issue. According to a poll released Wednesday by the UC Berkeley Institute of Government Studies, 60 percent of California voters surveyed disapprove of Biden’s performance on immigration, while only 30 percent approve.

With the election year approaching, Democrats would benefit by trying to neutralize immigration as a liability, though it remains to be seen whether cutting a deal with Republicans on the Senate proposal would achieve that to any substantial degree. Much of that may depend on the details of the agreement and whether Democrats could shave off some of the harsher edges of the plan, like detaining families at the border.

Further, many Republicans may not want to give up an effective campaign cudgel to pass what they consider a watered-down bill.

Vulnerable Democratic members of Congress have been increasingly pressing Biden to take a tougher line on immigration.

A handful of Democratic senators — John Tester of Montana, Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Joe Manchin of West Virginia — have co-sponsored a bill to give Biden expanded authority to expel migrants. The measure is co-authored by Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, the Democrat-turned-independent from Arizona. All are entering a re-election year, though Manchin announced Thursday he will not run again.

“We’ve got more than what we can handle in a really humane way,” Manchin told The Hill last week. “It’s putting strain all across the country. We ought to put a hiatus right now until we get our act together, so we’re going to be talking about that.”

Even Democratic governors and mayors have been calling for action — including tougher immigration limits in some cases.

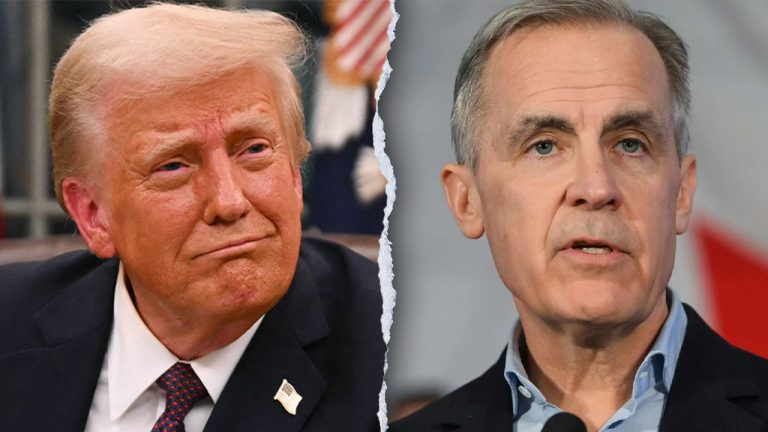

Meanwhile, Biden has essentially implemented some of the same border policies of former President Donald Trump that were once reviled by Democrats.

So, while Democrats couldn’t swallow the Senate GOP plan as is, many have been moving in the direction of stronger enforcement and a higher threshold for asylum that are in the proposal.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York initially called the plan a “total non-starter” largely because of the inclusion of Ukraine aid, but that was just an opening move.

A White House spokesperson was more measured, saying, “If Republicans want to have a serious conversation about reforms that will improve our immigration system, we are open to a discussion. We disagree with many of the policies contained in the new Senate Republican border proposal.”

Some GOP senators clearly believe they have the upper hand.

Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., told The Hill Republicans could be giving Democrats political cover by reducing the flow of migrants.

“If you’re being political here, we’d let the border continue to be a crisis,” he said. “But we can’t do that. We have to secure that border. We’re doing the Biden administration a huge favor by demanding they secure the border.”

That smug attempt at benevolence aside, it might benefit Republicans to show that, whether people like the policy or not, they can actually govern — something that has come into serious question, at least on the House side.

On that score, new Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., has said House Republicans would be working on their own border security package tied to Ukraine aid.

Among the things the White House and Democrats want to negotiate is a resolution to DACA, which was enacted by President Barack Obama in 2012.

Hundreds of thousands of people — including an estimated 10,000 in San Diego County — have been enrolled in the program that allows immigrants who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children to avoid deportation temporarily and receive renewable work permits.

Trump sought to end DACA, arguing the program required congressional approval. But the policy has been kept alive in the courts as litigation over the legality of Obama’s action continues.

That program has proved politically popular across the spectrum, though much more so with Democrats than Republicans. Also, studies conclude people in DACA, an offshoot of the unsuccessful DREAM Act, have been a boon to the U.S. economy.

At various times there appeared to be substantial bipartisan support in Congress for making DACA permanent, but standalone efforts have been stymied by other immigration concerns.

A trade-off for DACA in return for allowing Trump’s border wall to be built had some brief momentum nearly six years ago, but quickly fell by the wayside.

Part of the new Senate Republican plan calls for building that wall, though topography in some areas made Trump’s goal of erecting a barrier along the full length of the border with Mexico virtually impossible.

Biden now is building portions of the Trump wall that had previously received financial authorization. Biden and other Democrats have voted for border barriers in the past. So the dispute has become symbolic and may be resolved by how much or how little each side can live with.

It would be nice to think that something similar to a wall-DACA deal can be revived in the latest proposal.

But that’s probably dreaming.