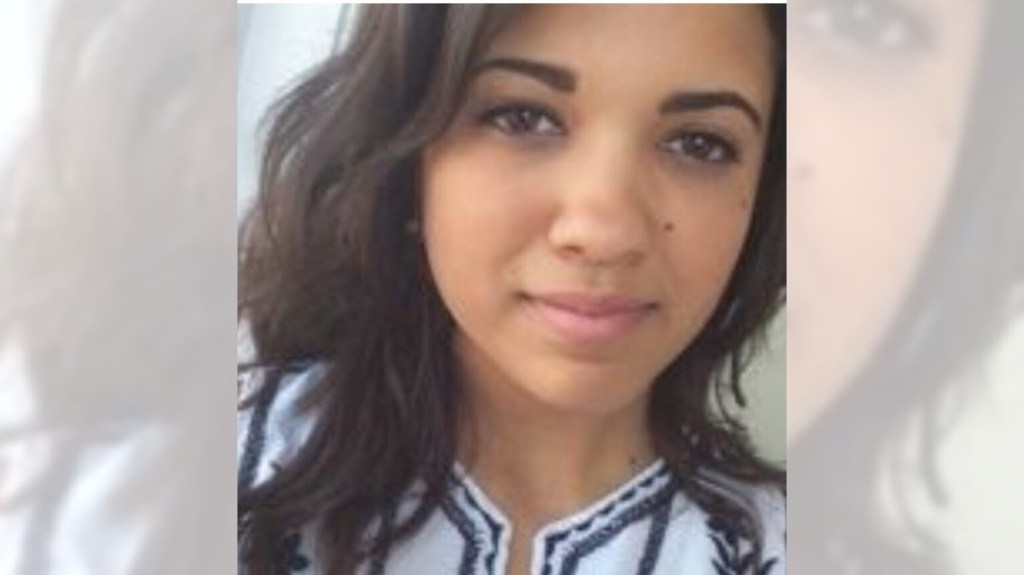

The mother of an Oceanside Navy medic who was murdered in 2018 by her upstairs neighbor, a mentally ill Marine Corps deserter who should have been legally barred from buying the gun he used to kill her, has agreed to settle two lawsuits against the government for a total of $10.5 million.

The lawsuits filed by Leslie Woods, the mother of 24-year-old Navy Corpsman Devon Rideout, alleged the Marine Corps and the California Department of Justice failed to properly submit information about the mental incompetency and background of Rideout’s killer, Eduardo Arriola, that would have landed him on an FBI database of prohibited gun owners and alerted the gun store it was barred from selling him a weapon.

“Devon’s death and the suffering her death has caused her mother … was entirely preventable,” Eugene Iredale, Woods’ attorney, told the Union-Tribune.

Woods agreed Monday to settle a federal lawsuit against the U.S. government for $4.5 million, pending final approval of the U.S. Attorney General, Iredale said this week.

Earlier this year, Woods settled a state court lawsuit against the California Department of Justice for $6 million, Iredale said. Court records showed that suit was formally dismissed in August.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office, which represents the federal government, declined to comment Friday. The Department of Defense and the Marine Corps did not respond to requests for comment. The state Attorney General’s Office, of which the California Department of Justice is a component, did not respond to a request for comment.

Arriola shot and killed Rideout on July 20, 2018, as Rideout was walking her new puppy, Chip, in their Oceanside apartment complex on Los Arbolitos Boulevard. Rideout had just finished her shift at a medical facility on Camp Pendleton and was still in uniform. Arriola, whom authorities said had no relationship with Rideout aside from living with his family in the unit above her, gunned down his victim just steps from her front door using a .38 caliber revolver he had bought from an Oceanside gun store weeks earlier.

At trial, an attorney for Arriola argued that her client was not guilty because he was so mentally ill that he did not have the capacity to form the intent to kill. Arriola was diagnosed with schizophrenia after deserting from the Marine Corps in 2014. A Vista jury convicted him of murder, and a judge sentenced him to life in prison.

Rideout’s mother sued the federal government in early 2022. The suit alleged that in 2016, Arriola was court-martialed for deserting from the Marine Corps and subsequently found mentally incompetent to stand trial. A judge ordered him to be involuntarily committed for three months at the U.S. Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Missouri.

“As such, he was prohibited from purchasing or possessing a firearm under federal law,” the lawsuit asserted. “But, in contravention of federal law and its own directives, the Department of Defense never reported Arriola’s mental illness and involuntary commitment to the FBI.”

The federal government denied liability in Rideout’s death and asked a judge to dismiss the lawsuit. U.S. District Judge Jinsook Ohta in San Diego denied the request, ruling last year that the case could move toward trial. A bench trial in front of Ohta was scheduled for late February before Iredale and a government defense attorney filed a notice on Monday that the case had settled.

Woods also filed suit in San Diego Superior Court against the California Department of Justice, arguing that it also had information about Arriola’s background that it did not properly act upon when he applied for the gun.

Iredale had learned through the federal lawsuit that when Arriola applied to buy the weapon in May 2018, an employee of the state’s Bureau of Firearms reached out to the Marine Corps for more information about the result of Arriola’s court martial. The response by a Marine Corps staff sergeant did not indicate that military authorities had dismissed the court-martial charge but did inform the state employee that Arriola had been transferred to the Federal Bureau of Prisons after being found incompetent to stand trial.

That information was enough to impose upon the state employee “a mandatory duty … to notify the firearms dealer to stop that transfer of the firearm,” the lawsuit alleged. But the state employee did not notify the gun seller, and Arriola was allowed to purchase the revolver.

That employee was initially named as a defendant in the lawsuit, but court records show that attorneys on both sides agreed to dismiss her from the case.

In both lawsuits, Iredale argued that the military’s failure to report disqualifying information about Arriola to the FBI under the Brady Act, the federal law that mandates background checks, was part of a pattern and not a one-time mistake.

A series of reports published by the Department of Defense’s Inspector General between 1997 and 2017 found that the country’s military branches consistently failed to meet their reporting obligations at a high rate. The 2017 report, the most recent report from before Rideout’s killing, found that during 2015 and 2016, the branches did not submit 31% of the “final disposition reports” they were required to by law for military members convicted of crimes. That number was even higher, 36%, for the Navy and Marine Corps.

“Time and again, the Inspector General called out the Navy and Marines for their repeated failures to make the reports on prohibited persons to the FBI,” Iredale said this week. “Time and again, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, Navy and Marines would acknowledge their failures, voluntarily undertake to comply and remedy these failures, and would then continue the pattern of failing in up to one-third of the cases to make the required report to the FBI.”

As one recent Inspector General report noted, such failures can end with tragic consequences. The man who committed a mass killing in 2017 at a Baptist church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, was an Air Force veteran convicted of assaulting his wife who should have been prohibited from buying guns.

“The Air Force failed to submit the fingerprints and final disposition report of Devon Patrick Kelley,” the Inspector General report noted. “This omission allowed Kelley to pass a background check and purchase … the firearms he (used) to kill 26 people and wound more than 20 others.”

The same Inspector General report noted that by 2019, the military’s various law enforcement agencies had implemented new policies, procedures and oversight that resulted in 100% compliance with submission requirements.