Climate change policies are increasingly likely to have an impact on inflation over the next two to three years, a top Bank of England policymaker has warned.

Climate change and countries’ different approaches to combat it are likely to boost inflation and have other economic impacts that are directly relevant to central bank rate-setters.

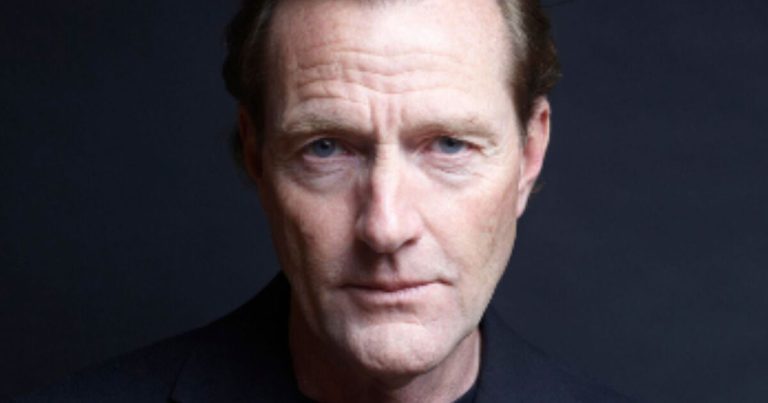

The application of net zero policies promopts a potential rise in operational costs for businesses which causes fear for consumers as these high prices could be pushed forward, Catherine Mann, a prominent member of the Monetary Policy Committee at the Bank of England explained.

The climate change policies include carbon taxes and emissions trading schemes.

Ms Mann was part of a minority of three Monetary Policy Committee members who voted this month for the BoE to raise its main interest rate to 5.5 percent from 5.25 percent.

She said: “The research here points to increased inflation, increased inflation persistence, and increased inflation volatility associated with climate shocks, policies, and spillovers.

“Evidence has suggested upward pressure on inflation [and] downward effects on output.”

The warning comes at a tough time for the Bank of England and for British households, with inflation still running at 6.7percent.

This is more than three times the Bank’s two percent target. At the same time, recent figures have shown the economy is stagnating.

It comes after the Government rowed back on some of its net zero policies, delaying a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2030 to 2035.

In September the Prime Minister also said he would delay the ban on new oil-fired boilers from 2026 to 2035, and increase grants for heat pumps.

The Bank of England’s emphasis on climate change and net zero policies in relation to inflation has been faced with ongoing criticism.

However, the Bank believes the effects of climate change on the macroeconomy are a critical area requiring research and understanding.

Ms Mann continued: “Not only is it within my remit to respond to the macroeconomic effects of climate change, but, in my view, my remit requires me to do so.

“When climate change has macroeconomic effects – whether physical impacts from extreme weather events and higher average temperatures or transition effects associated with transforming to a net zero economy, including explicit implications for inflation – it becomes a concern for monetary policymakers, directly within a price stability mandate.

“That applies whether the monetary policymaker’s remit includes a reference to climate change or not.”

Ms Mann has constantly drawn attention to the relationship between climate change, net zero policies, and their implications for inflation – she has consistently voted for higher interest rates than the majority of the nine-strong MPC.

Net zero policies affect inflation as governments seek to push businesses away from established, but polluting production methods and into new greener methods.

But this means piling extra costs onto polluting businesses “presumably to be passed on fully or in part to consumers, which prompts the behavioural change needed to reduce emissions”.

Even if consumers themselves choose to buy less polluting products, the extra demand will push up prices until companies can boost the supply of the greener goods and services, Ms Mann added.

This week, Britain will find out the latest inflation figures for October, with the consumer prices index widely expected to fall below five percent in a boost for Rishi Sunak.

The Prime Minister promised he would halve inflation by the end of the year, meaning it needs to fall below 5.3percent. Analysts expect a drop to 4.7percent in figures to be published on Wednesday.