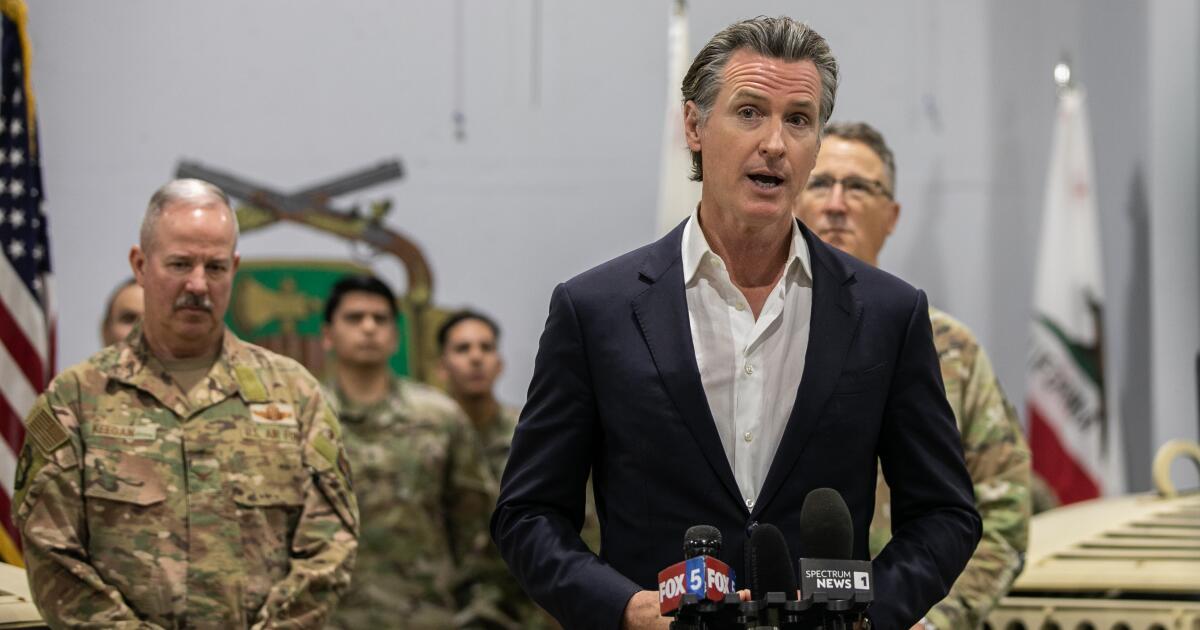

California National Guard members assisted law enforcement agencies across California last year in seizing more than 62,000 pounds of fentanyl, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced this week.

Though CalGuard soldiers assigned to support roles at San Diego-Mexico border crossings have drawn much of the spotlight in recent years, seizures along the border make up only a small fraction of the fentanyl seized in CalGuard-supported operations. Rather, the assistance largely came in the form of soldiers from CalGuard’s Counterdrug Task Force working as crime data analysts in what are known as High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas.

Newsom touted the seizure numbers — a huge increase from the previous two years, and worth an estimated street value of $649 million — as one part of what the state is doing to fight fentanyl, a highly potent synthetic opioid that can be deadly in very small doses.

“Fentanyl is a poison, and it does not belong in our communities,” Newsom said in a statement. “California is cracking down — increasing seizures, expanding access to substance abuse treatment, and holding drug traffickers accountable to combat the immeasurable harm opioids have caused our communities.”

Local, state and federal law enforcement agencies across California seized 5,334 pounds of fentanyl in 2021 in operations directly supported by CalGuard, according to state officials. That figure jumped to 28,765 pounds in 2022 and 62,224 pounds in 2023.

Those huge jumps in the last two years were a function of both an increase in the fentanyl supply in the state, but also a more focused effort by CalGuard’s Counterdrug Task Force to target the drug.

The task force is made up of about 370 full-time, active-duty soldiers, National Guard Maj. Gen. Matthew Beevers told reporters in September. Last year, the task force received $26 million in funding from the federal government and $15 million from California’s budget.

“It’s extraordinary,” Beevers said of the state investment during the briefing last year, adding that it goes to show the “unique challenges” that California faces in terms of drug trafficking as a border state and one with a long coastline ripe for smuggling.

“The California National Guard is committed to combating the scourge of fentanyl,” Beevers said in a statement this week. “These extraordinary seizure statistics are a direct reflection of the tireless efforts of the highly trained CalGuard service members supporting law enforcement agencies statewide.”

In San Diego County and neighboring Imperial County, that support largely comes in the form of guard members stationed at ports of entry, where they provide support to U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers.

“(They) fill vital secondary positions that would otherwise be staffed by CBP officers, taking them away from more law enforcement-centric duties,” CBP spokesman Michael Scappechio told the Union-Tribune.

Scappechio said the guard members often help guide drivers who have been referred to secondary inspection areas, ensuring the drivers correctly maneuver through a large X-ray machine on the way. The soldiers then help monitor the vehicles and drivers while they wait for CBP officers to review the X-ray images. If CBP officers notice anomalies in vehicles, the soldiers sometimes help disassemble vehicle parts to look for hidden drugs.

All of that helps free up CBP officers who can focus instead on primary inspections, investigations and other law enforcement functions, Scappechio said. Officials say the support has worked well, and Newsom in September ordered a 50-percent increase in guard members at ports of entry, where the bulk of illegal drugs cross the border into the U.S.

But border seizures make up just a small part of the fentanyl seized throughout the state. According to CBP statistics, the agency’s San Diego field office seized about 10,250 pounds of fentanyl in 2023, and only a portion of that number would be considered directly supported by CalGuard.

The rest of the fentanyl seizures occurred in the interior of the state. And the support from CalGuard members, who do not have law enforcement or investigative authority, largely came by way of crime data analysis.

“Our value is really behind the scenes … where we’re providing information back to law enforcement that enables them to do their jobs better, and frankly faster,” Beevers told reporters during the briefing last September. As an example, he pointed to the personnel that Newsom sent to San Francisco last April to battle fentanyl-trafficking rings.

“We continue to help them analyze information … so as San Francisco PD makes arrests, the intelligence or information is shared up through the High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, where our analysts aggregate that data to try to understand how the criminal networks are operating in that city,” Beevers said. “And from that, we can make reasonable assumptions on who these folks are, how they operate … and share that with our law enforcement partners, which enables them to make more arrests and really get after the problem.”

In addition to deploying soldiers to ports of entry and as analysts, CalGuard’s drug task force also runs an educational Drug Demand Reduction Outreach program aimed at keeping school-aged children away from drugs.