Failures by sheriff’s deputies to conduct proper jail checks preceded two men’s deaths behind bars a month apart, the county’s law enforcement oversight board has found — and the family of one man says he should never have been in jail in the first place.

Matthew Settles, who was 54, had long suffered from schizoaffective disorder and was under a court-ordered conservatorship, a status reserved for people who are deemed unable to care for themselves.

Records show he was neglected after being transferred to the Otay Mesa jail in 2022 and killed himself in an isolation cell within weeks.

Settles was one of 19 people to die in sheriff’s custody that year, not including one man who died in a hospital hours after he received a compassionate release. At least 20 others have died in San Diego County jail custody since the beginning of last year.

Martinez was not the sheriff when Settles died by suicide at the George Bailey Detention Facility in August 2022.

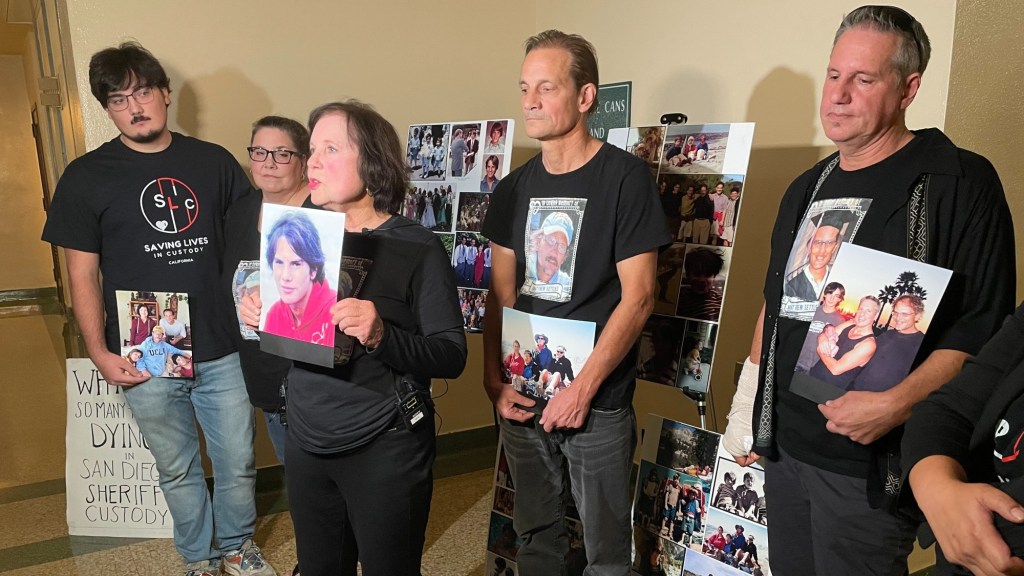

But his relatives and advocates with Saving Lives in Custody California argued Tuesday that she has resisted some reforms and noted she had recently argued that the push for stronger oversight was fueled by activists intent on doing away with jails.

“There were monumental failures that happened to Matthew Settles,” said Yusef Miller, executive director of Saving Lives in Custody California. “But instead of an ally, we have an opponent.”

A Sheriff’s Office spokesperson said she could not comment on Settles’ case because his family has filed a lawsuit.

Department officials have previously said they do the best they can to protect people in custody and continue to make safety improvements.

In their report to the review board, CLERB investigators said deputies failed to check on Settles’ safety as directed by department rules and state regulations, which require deputies to observe each incarcerated person and “look for signs of medical distress, trauma or criminal activity” at least once every hour.

A sheriff’s report had said checks were done at 6 p.m. and again at 6:57 p.m., but video evidence showed otherwise. According to investigators’ findings, deputies passed by Settles’ cell at approximately 6:04 p.m. and 7:19 p.m.

In another case discussed Tuesday, CLERB investigators found similar policy violations in another death at the George Bailey jail just one month earlier.

Abdiel Sarabia was discovered unresponsive inside his cell in July 2022.

In his case, deputies also failed to conduct timely safety checks, the investigation found. When the last sworn officer visited the housing module, he completed a welfare check of 34 detainees in less than 30 seconds — even though he was supposed to check each person individually.

“(Sheriff’s Office) documentation showed that when deputies responded to the incident at 10:13 a.m., Sarabia was cold to the touch, had a bluish skin tone and described him as ‘stiff,’” the CLERB report said.

Investigators urged the board to recommend that the Sheriff’s Office adhere to policy.

“It is recommended that SDSO take all necessary measures to change its current practice … by mandating that every incarcerated person be directly observed by sworn staff at intervals not to exceed 60 minutes.”

State regulations and sheriff’s policy also require that people in medical beds and psychiatric units be checked every 30 minutes and those in safety cells every 15 minutes, investigators noted.

It’s not the first time the Sheriff’s Office has been warned that its safety checks are inadequate. A state audit released in February 2022 — months before Settles and Sarabia died — had already urged more thorough checks, among other recommendations, to make San Diego jails safer.

“Based on our review of video recordings, we observed multiple instances in which staff spent no more than one second glancing into the individuals’ cells, sometimes without breaking stride, as they walked through the housing module,” auditors wrote at the time.

“When staff members eventually checked more closely, they found that some of these individuals showed signs of having been dead for several hours,” they added.

Settles’ family held a news conference inside the County Administration Building on Tuesday evening, before the CLERB meeting.

He needed treatment, not jail, his brother David said. In jail, Matthew’s physical and mental health deteriorated. He was assaulted by another detainee and harmed himself multiple times, including jabbing himself in the eye with a syringe.

Unlike the Central Jail, where Settles was initially housed, George Bailey Detention Facility has no specialized unit for mentally ill detainees.

Grace Jun, one of the lawyers representing the family, said the CLERB investigation into Settles’ death should have considered the harmful effects of isolation on someone so seriously mentally ill.

“Did CLERB ask who ultimately decided to keep Matthew Settles in administrative segregation, even when his medical records indicated he was decompensating and doing poorly in solitary confinement?” she asked. “Was it the fault of medical staff, or did custody staff override the recommendations of mental health professionals?”

Currently, CLERB lacks the authority to investigate whether a detainee received adequate medical care. But that will change next year.

Last week, the county Board of Supervisors voted to extend the review board’s oversight to medical and mental health staff in death cases. The change, which still needs to be negotiated with labor unions and added to county rules, is expected to be implemented next year.

The Settles and Sarabia families are two of many that have sued San Diego County over deaths in custody.

Taxpayers have spent more than $57 million on jury awards and legal settlements related to sheriff’s negligence and misconduct in jail deaths and serious injuries since 2019, records show. The cost is likely to grow as other cases move forward.