Thinking about coming together for a family meal brings up images of food, conversation, and gathering. That same space can also carry an understanding of social hierarchies and walking a kind of conversational tightrope in the desire to be seen and heard. The organizers of “Queering the Table: An Asian Tapestry of Language, Connection, and Queer Presence” want their event to be a beginning of a different conversation in that space.

“We want this to be a gathering point for queer Asians, but we would also like to have a collective sensing of the difficulties that our bodies go through,” said Jun!yi Min, a performance artist studying for her master’s in fine arts at UC San Diego, who worked on the event with Emily Tran, of Viet Vote, a local nonprofit working to build civic engagement among San Diego’s Vietnamese community. “It is important for me to feel that we are starting a conversation, but we also have a collective memory of the imageries, the emotions, the tensions—through the words, through the performances—that we can ruminate upon and, for future iterations, to discuss more. So, I think of it more as a starting point.”

The event, from 5:30 to 9:30 p.m. Monday at the Mingei Museum in Balboa Park, features visual art and performances by local, queer Asian artists, along with food and drinks. Min describes video documentation of Einar Escoto performing his one-man show, exploring his transition and reckoning with his family’s acceptance, along with his own acceptance of his body and gender; imaginative, speculative work in ceramic by Cat Gunn, which deals with altars and seeking a spiritual relationship with their Filipino ancestors; a display of photo transfer on silk of one of Min’s past performance pieces where she crawls into a cocoon and transforms inside of it; performances by Min, Hamsa Nguyen (who will perform poetry about diasporic experiences), and Escoto performing parts of his one-man show; and a facilitation of talks between performances by Britt Pham.

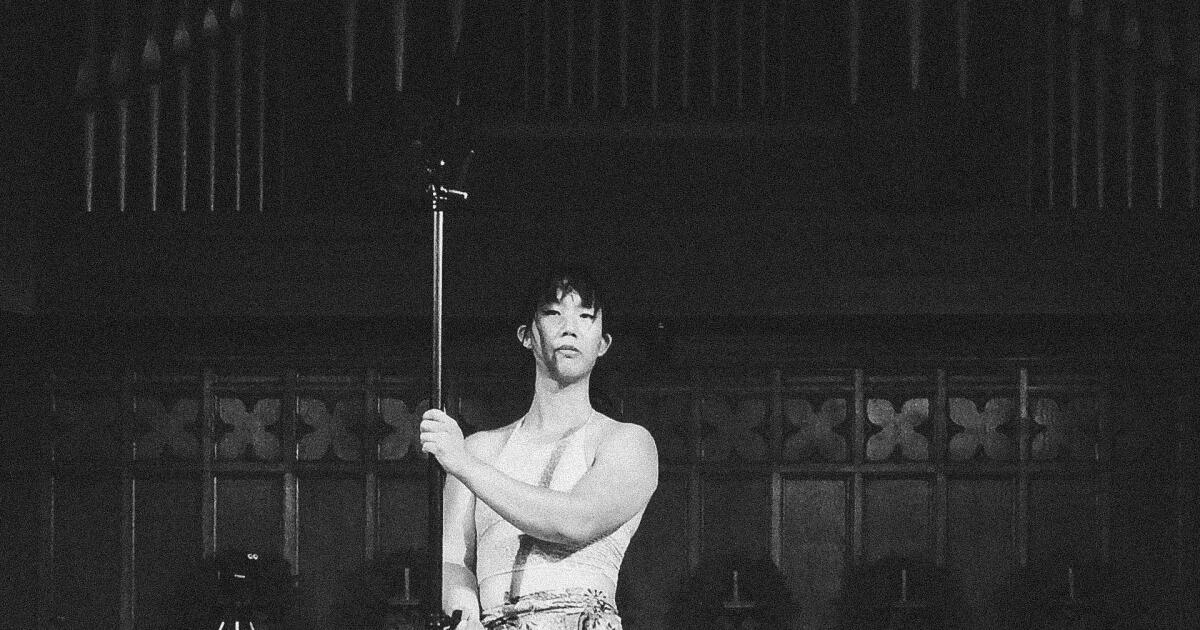

Min describes her endurance performance artwork as focused on “queering Asian familial ties” and trying to “challenge my audience’s sensitivity of looking, and also cause the audience to witness and extend care to the enduring, performing body.” One of her pieces involved her lying in the front end of a bulldozer and spending the night there, enduring the contradiction of being a trans-feminine person in a piece of machinery considered masculine and destructive, attempting to make a temporary home in the space. She took some time to talk about “Queering the Table” and her own experiences navigating the traditional family gathering in her personal life. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity. )

Q: “Queering the Table” is an event that you have collaborated on, in partnership with Viet Vote and the Asian Solidarity Collective. How did this event come about? How did the two of you come together to create this?

A: One of the main organizers of Viet Vote, Jean-Huy [Tran], came to my studio during one of the open studio visits at UC San Diego. He came in and he saw one of my works, the cocoon piece that I’ll be performing. He saw that work and he was very interested in just working with me further to re-perform it, but also to curate a space for queer Asian bodies to gather. Afterward, he assigned one of his coworkers, Emily Tran, and we have been working together over the last few months to come up with “Queering the Table.” We realized that we really wanted to talk about a lot of experiences because there’s not enough gathering happening, there’s not enough communal sharing that happens in San Diego, specifically for queer Asians, so we wanted language to be a part of it, especially when we start reflecting on familial tensions where we have a loving family, but one that does not like to speak about certain issues, especially queerness. So, that’s why we started working with Britt [Pham] and asking them to help facilitate some of the conversation and we wanted to make sure that this is an exhibition that is accessible to people. We didn’t want it to be where the artists become this high figure raised on a pedestal and almost not understandable, so we wanted to bring language and to help translate to help the audience see better.

Q: In the description of “Queering the Table” online, it says that “the familial dinner table is often a daunting space for queer Asians because of unspoken games, awkwardness, hierarchical ideology, and passive aggressiveness.” First, can you help us understand how you define your use of the word “queer”?

A: I think of “queer” as providing alternatives. I think of it as thinking outside of the box, outside the norm. I think there’s an understanding of queer as negation, which is not always super helpful because it’s like in the negative space. When I see the word “queer” I relate it to negation, but I see it more as all of the beautiful things outside of the boundary, so it feels a little bit different. It’s not the negativity of it at all; it’s a negation to straightness. It’s a negation, not to negate anything but it’s all of the things outside of this boundary that we have drawn. Looking out of the house, looking out of the structures that we have built.

Q: Do you mind sharing your ethnicity and the role that the familial dinner table has played in your own family?

A: I am Chinese. I was born in Shanghai and both my parents were Chinese immigrants and I immigrated to Singapore when I was 3, and naturalized as a citizen. Regarding how it plays in my own family, the dinner table is always a gathering space, always for us as a family unit to come together and feel as one and also feel at home. Of course, food, we like to partake in together and we also try to talk at the dinner table. The talking is always quite limited, especially with father figures who are reticent. That kind of effect is felt in my family, especially when the father doesn’t really want to talk, like to talk. It feels like, sometimes, the dinner table becomes more of a farce. We’re not really gathering as a unit, we’re not really gathering spiritually because our bodies are present, but emotionally and spiritually they might not be on the same page if we can’t even talk about things. In my own practice with my family, because I care about queering those kinds of dynamics also, a lot of times I try to use these gatherings—and it’s just the four of us, my parents and my younger brother, who’s 15 years younger than me—as an opportunity to talk about other issues around the world and also about family intentions. I want to use this family table to talk about these issues, to resolve interpersonal issues between my father and my mom, between my brother and my parents, between me and my parents, and also bringing in topics about queerness that they find hard to understand and hard to face. For me, the dinner table becomes a place where we have to face each other and face ourselves, our fears. I think I’m mostly speaking here to my father [Min chuckles], but there’s a lot of difficulty for him who’s seen as being the head of the table, right? To even face himself and to face me. So, I would like, with “Queering the Table,” at least, I would like to reinvite this ability to look at and face our own fears, our own desires.

Q: What has been your own experience with the “unspoken games, awkwardness, hierarchical ideology, and passive aggressiveness” at this kind of family gathering, as a queer Asian person?

A: I usually do two things. One, I try to be as sharp as I can and direct about certain issues, and seeing it for what it is. Instead of beating around the bush with the unspoken games and stuff, I would just directly address things. Thankfully, my parents are able to do that with me and they don’t always just recoil. At the same time, I know that while I need to be sharp and be assured that what I’m doing is right for the family, I also have to extend care in how I say things and how I accept them as individuals who are also learning from me. That’s where I see the dynamics of parent-child relationships and queering — as time passes, I start knowing more about the world and about how to usher in a better future or a healthier relationship through my ongoing sessions in therapy, my own readings of restorative justice, and how to usher in a more free future. I start learning more than they have and there’s a kind of intellectual hierarchy that is being inversed and I do more of a teaching role in the family. So, I try to do it with insightful thoughts, but also in a way that cares for how they feel as individuals and accepts what they think and try to work with them. I want to give them the far end goal in mind; they might see it, they might not see it, but I’m willing because of all of the love that I have received and the kinds of sacrifices my parents have done for me. I’m willing to guide them and that’s my duty as a daughter. At least, how I think of it, to guide them because they have made my life so happy, it is my duty to reciprocate.

Q: The Human Rights Campaign, The Trevor Project, and the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law have each released reports about the specific experiences and challenges of the almost 700,000 LGBT Asian American/Pacific Islander adults and youth in the U.S., with suggestions for finding culturally relevant and competent support groups and informational resources. What has been helpful to you in navigating that awkwardness and passive aggressiveness in those family spaces?

A: Honestly, friends [laughs]. Other queer Asian friends who are also radical and also on the same journey. To be able to talk to them is just so wonderful and it feels like I’m able to pull from this larger resource where we are all collectively sort of working together toward a happier relationship with our own parents. I think that’s why I want to gather people during “Queering the Table,” to create this kind of locus for creatives to gather, meet each other, and witness and have this collective memory of this day.

One last thing is that I talked about witnessing and the importance of witnessing together. I feel like a lot of queer and trans narratives and experiences are being rendered invisible and we want this to be the stage where what is unheard, what is unseen, can stand proudly in front of people.