There’s a battle under way in a specialized San Diego court program for criminal defendants with a serious mental illness, a tug-of-war that may be stalling the program from accepting new participants.

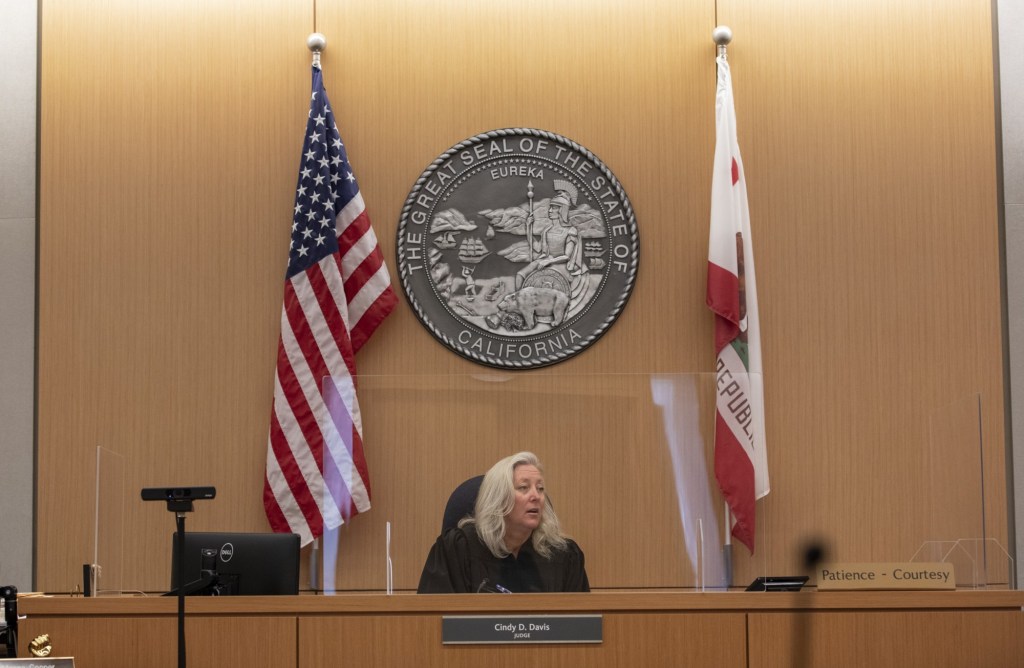

Several times since last summer, the District Attorney’s Office has asked the Superior Court judge overseeing Behavioral Health Court to recuse herself from hearing cases involving referrals of potential participants to join the court program. Judge Cindy Davis has generally refused to do so.

Prosecutors took their fight to a state appeals court, arguing in court documents that Davis has admitted “inappropriate participants,” overlooked input from the team that makes up the collaborative court, and “struggled” to hold participants — who are all criminal defendants — accountable.

“Over the last few years, we have become increasingly alarmed by Judge Davis’ decision-making,” prosecutors said in a January court document laying out why they are seeking her recusal.

The prosecuting agency pointed to the admission of a woman who starved her infant to death and to the overdose deaths of three Behavioral Health Court participants in quick succession. One had continually failed his drug tests, but they say Davis gave him second chances, not punishments.

It was under those “grave circumstances” that the District Attorney’s Office says it began challenging Davis as the judge for probation cases referred to Behavioral Health Court.

“This decision was not made lightly,” the petition reads.

The court, which is bound by ethical rules disallowing judges from commenting on pending cases, declined comment.

Technically, the battle is over whether prosecutors can seek Davis’ recusal in hearings to accept defendants into the program. The legal question is whether it is a contested hearing, the kind of hearing where they can ask for another judge.

Until the appeals court makes a ruling, at least two cases remain in a holding pattern, and those two defendants sit in jail waiting to see if they can join the program.

No new defendants have been accepted into the program since December, although it’s not clear why. One attorney said prosecutors are no longer agreeing to have Behavioral Health Court on the table in plea deals. The program consists of four phases over at least 18 months. As of last week, there are only two people in the first phase and just one in Phase 2.

The District Attorney’s Office and Public Defender’s Office declined comment on the matter.

Court program for mentally ill defendants

Behavioral Health Court is a small program in San Diego Superior Court, offered to a fraction of felony criminal defendants who meet qualifications, including diagnosis of a serious mental illness — often schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder.

The idea is to address the needs of mentally ill defendants deemed suitable for program offerings. Often, the people allowed to join go directly from jail into a group home. They get treatment, medication, group therapy and individual counseling.

Officials have sung the praises of the specialized court. County Supervisor Jim Desmond has called it an “excellent program” and successfully sought to increase county funding to create more spots for people on probation.

The Union-Tribune reported in 2022 that the court had a completion rate of 56 percent, considered a success rate given the difficulty of the population. Nearly 80% of those who complete the program had stayed out of criminal trouble in the immediate aftermath of graduating.

“I really view this as saving lives, changing lives,” Davis said at the time. “They get to a point in their life where they’ve been in and out of hospitals or in and out of jail enough times that they want to make a change.”

It is a collaborative court. At the table are a Superior Court judge who leads the group, with a deputy district attorney, a city attorney, a public defender, probation officers and a contractor tasked with service and treatment.

The group meets weekly to talk about who to accept, who is on track, who needs help and who is failing. The judge makes the final call.

The court has been around since 2009. Davis has led it since 2019.

The challenges to her started last summer. The background of the conflict — primarily from the perspective of prosecutors — is laid out in filings with the 4th District Court of Appeal.

The District Attorney’s Office says in court filings that it opposes her decisions regarding who has been allowed into the program and how participants are sanctioned for rule violations.

“The BHC program is in crisis and the People have been left with no choice but to file peremptory challenges to the judge who is responsible,” prosecutors wrote in a Jan. 21 court filing.

Such challenges to judges have been rare under District Attorney Summer Stephan, who has been in office about seven years. Court documents from prosecutors indicate this is the third time her office has challenged a judge, and this is the first time they have sought that judge’s recusal on multiple cases.

“The decision to challenge was based on long-observed practices by Judge Davis of giving little weight, if any, to the opinions and recommendations of highly trained mental health experts, or to the other partners including the People,” Assistant District Attorney Dwain Woodley wrote in a declaration filed with the appellate court.

In filings, prosecutors highlighted cases of “the most troubling circumstances,” including that of a woman who allowed her 2-month-old daughter to starve to death, even as her husband — a Navy sailor stationed out of state — pleaded with her to get the infant medical help after hearing during phone calls the baby’s cries.

Prosecutors allege the woman had no documented mental health treatment history, a basic requisite for Behavioral Health Court. They said Davis admitted the woman into the program “over strong opposition” from not just them but also the treatment team and the Probation Department representative.

Prosecutors said in January that defendants in two “violent and disturbing cases” were referred for screening as potential candidates for the court. One involved the case of a woman accused in the death of her former landlord, the other a woman accused of stabbing her elderly father in his hand.

Davis declined to recuse herself. Those two cases are on hold while prosecutors file appeals.

Attorney Brandon Naidu, who represents the woman accused in the death of her landlord, declined comment on the pending litigation. However, he laid out arguments in a declaration filed in the appellate case.

Naidu argued the prosecution’s challenges “demonstrate an improper attempt to circumvent the prospect of defendants being accepted into a collaborative court program that they disagree with and removing a judge whose rulings they dislike.”

He said their argument is reduced, in part, to the “claim that Judge Davis is biased and unfair due to her admitting certain individuals over their objections …”

If prosecutors prevail, Naidu said in the declaration, “this undoubtedly will affect all collaborative courts, as attorneys who are unsatisfied with the judges in those Courts whom they perceive as being ‘too strict’ and ‘unfair’ to their clients could now successfully challenge these judges.”

Attorney Domenic Lombardo is the immediate past president of the San Diego Criminal Defense Bar Association, and he has represented several clients in Behavioral Health Court. He said prosecutors are not putting the program on the table in plea deals.

“I think Judge Davis has demonstrated herself to be the type of jurist possessed of unimpeachable independence and conviction,” Lombardo said, saying she is attentive to the program participants. “She is the personification of the most compassionate in government. And that is who these people need.”

Recusal requests denied

The legal battle before the appellate court is not over the merits of the two cases in front of it, but rather a more technical question: Does the law allow prosecutors to challenge Davis during hearings to admit defendants to the collaborative court?

The law requires that challenges to judges happen only in hearings where facts and law are contested.

The District Attorney’s Office argues that the admission hearing is essentially a sentencing hearing — the defendant is sentenced to probation and to join Behavioral Health Court. They argue that sentencing hearings, by nature, are adversarial and contested.

Each side gets one challenge to a judge. They don’t have to say why they are doing so.

This is not a blanket challenge to Davis. Prosecutors are only challenging her in cases involving Behavioral Health Court or mental illness.

When prosecutors filed their first request for recusal last summer, Davis granted it. Judge Paula Rosenstein was assigned to the case. She later learned that prosecutors had challenged Davis again in another case, and that Davis had declined to step aside. Rosenstein said she agreed with Davis’ reasoning in her refusal to recuse and sent her case back to Davis.

Between July and October, Davis denied 11 requests to recuse herself.

In her orders denying the challenges, Davis says the admission hearings are not addressing contested matters, so the law doesn’t require her recusal. As such, she found that prosecutors had failed to meet their burden to force her disqualification.

The deputy public defender in Behavioral Health Court, attorney Melissa Tralla, submitted a declaration to the appellate court in which she says Davis’ order to deny the challenge was correct. Tralla said in her declaration that issues of law are not discussed when deciding to admit a new participant and that the facts of the case are uncontested.

“While there can sometimes be disagreement, more often than not the stakeholders agree as to who is appropriate and who is not appropriate for BHC,” Tralla wrote.

The legal battle now lies in the appeals court. Prosecutors have requested time to argue their case to a panel of appellate judges. No date has been set.

Originally Published: