Opera is an art form that has been around for more than 400 years. But not mariachi opera. This hybrid form of contemporary opera and the Mexican tradition of mariachi folk music got its start just 13 years ago.

In 2010, the world was introduced to the art form of mariachi opera with “Cruzar la Cara de la Luna (To Cross the Face of the Moon),” which premiered at Houston Grand Opera and has since played all over the country, including at San Diego Opera in 2013.

The co-creators of “Cruzar” and a second mariachi opera five years later, “El Pasado Nunca Se Termina (The Past Is Never Finished),” were famed Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán bandleader and composer José “Pepe” Martínez of Mexico City and American librettist Leonard Foglia. It, too, was presented by San Diego Opera in 2015.

Less than a year after the premiere of “El Pasado” — a love story set on the eve of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 Morelos, Mexico — Pepe Martínez passed away at age 74.

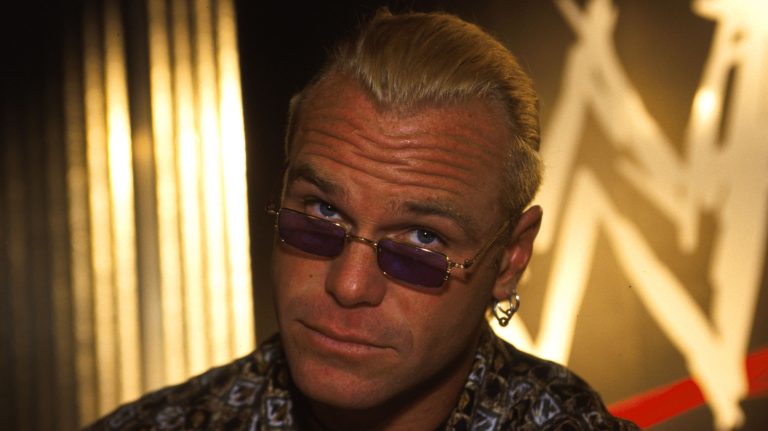

Javier Martínez is the composer of San Diego Opera’s “El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering).”

(Courtesy of Carla Lorena Sánchez Muñoz)

But the fledgling tradition of mariachi opera did not die with him. Pepe’s son, Javier Martínez — also a long-established mariachi bandleader, musician and composer — is carrying on the tradition. With Foglia, José Martinez wrote the Christmas-themed “El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering),” which also premiered in Houston in 2019 and is being presented by San Diego Opera next weekend at the San Diego Civic Theatre.

In a Zoom interview from his home in Léon, Mexico, earlier this month, Javier Martínez said he is happy to continue the work his father started, and he’s especially proud to have put his own creative stamp on the genre with “El Milagro.”

“It was amazing to see it come to life again because this one is my little baby and I watched it getting bigger and bigger until the day of its premiere. It truly is a dream come true,” he said.

The birth of mariachi opera

The idea for combining the centuries-old art of opera with the early 19th-century creation of mariachi was dreamed up by Lyric Opera of Chicago General Director Anthony Freud after he saw a live performance by Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán — which “Pepe” Martínez led for nearly 40 years — at Houston Grand Opera in 2007.

In an interview last April with the Smithsonian Institution’s FolkLife magazine, Freud said he wondered if there would be a way to bring mariachi not just into an opera house for a concert but into the opera genre itself.

“I envisioned an opera which merged the traditional short-form songs of mariachi with a coherent story and musical structure, but would never stray from being authentic mariachi,” he told FolkLife. “The last thing I wanted was some sort of ‘mariachi-light,’ crossover piece. I wanted the real thing, but with its outer limits stretched to become something new. Mariachi and opera would be on equal terms, and the culminating result would break down boundaries that had confined both.”

Leonard Foglia is both the stage director and librettist for San Diego Opera’s production of “El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering).”

(Courtesy of San Diego Opera)

Freud contacted Pepe Martínez to gauge his interest in such a project, and then reached out to Foglia, to serve as the librettist. Foglia is best known as a theater director (his Broadway credits include Terrence McNally’s Maria Callas-themed 1995 play “Master Class”) and as a novelist, but he also wrote the opera libretti for Jake Heggie’s “The End of the Affair” and Ricky Ian Gordon’s “A Coffin in Egypt.”

Javier Martínez fondly recalls the day he and his father, Pepe, were invited to visit Foglia at his home in Querétaro, Mexico, to discuss their first opera project.

“I remember we had an appointment at Lenny’s house in Querétaro, and when we got there my father said ‘well, there’s no such thing as mariachi opera’ and Lenny said ‘well, would you like to join me in making it?’ That was how it was born,” Martínez recalled earlier this month.

Mariachi, which got its start in the early 1800s in Mexico’s Western states, is the nation’s traditional folk music. The music, which blended indigenous, Spanish and African styles, began with bands playing guitarrón (extra-large bass guitars), violins and harps. Brass instruments and other string instruments came along much later, along with the traditional Mexican charro (cowboy) outfits and sombrero hats associated with mariachi.

Martínez said that while mariachi music was has deep historical roots in Mexico, it exploded in popularity in the mid-20th century when Mexican film directors started including mariachi bands and music in all of their films.As a result, mariachi singers became superstars.

One of Mexico’s oldest mariachi bands, and what many Mexicans consider the greatest, is Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán, which was founded in 1897 in the small town of Tecalitlán, southwest of Guadalajara. Martínez said that his family’s connection with Mariachi Vargas goes back two generations. His grandparents on both sides of his family, as well as his father Pepe, all played in the band, as well as many cousins and uncles.

A scene from San Diego Opera’s mariachi opera “El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering),” which plays Dec. 1 and 3 at the San Diego Civic Theatre.

(Courtesy of San Diego Opera)

Raised in Mexico City, Javier Martínez started his mariachi career at 17 as a violinist and singer. He never performed with Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán but since 1995 has been a performer with eight different mariachi bands, as well as a bandleader, composer and record producer.

His journey into mariachi opera began in 2015, when his father and Foglia were finishing work on their second opera, “El Pasado,” but his father’s declining health made finishing the piece impossible, Martínez said.

“It was very hard to do because I live in Léon and he lived in Mexico City. My sisters would scan the documents and send them to me with the recordings, and me and my father would talk (on the phone) about it and he would tell he how he wanted everything to sound. It was three months of working long distance and the last time we worked together.”

Martínez served as his father’s arranger for the score and song lyrics on the second opera, but he composed the entire score of the third with Foglia, “El Milagro.”

Martínez said his opera isn’t sung-through like traditional opera. There is some spoken dialogue in between songs in “El Milagro,” and there are three mariachi musicians who sing and play onstage with the opera singers.

“I think the difference between mariachi and mariachi opera is the matter of theatricality,” he said. “It’s different when we write a song for mariachi because it’s just one theme. In mariachi opera we put more emotion into the music through the words of the writer, in this case Lenny. It was very new to me as a writer, but the music has to reflect the words and emotions of the story.”

At the 2019 world premiere of “El Milagro,” Martínez said he was thrilled not only at how it turned out but also the diversity of the audience who came to watch — Americans, Mexicans, Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans as well as families with children.

Freud, in the FolkLife interview, said he’s also been excited to see how well audiences have received mariachi opera.

“My idea for a mariachi opera was born on a wave of emotion when I experienced mariachi in 2007 for the first time,” he said in the article. “More powerful has been the many occasions where people of diverse backgrounds, ethnicities, ages, and life experiences have said to me, ‘You are telling my story’”— a story of many divided families who have had to redefine where home is.”

A scene from San Diego Opera’s mariachi opera “El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering),” which plays Dec. 1 and 3 at the San Diego Civic Theatre.

(Courtesy of San Diego Opera)

The ‘El Milagro’ story

The 2019 opera “El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering)” was written as a prequel to the 2010 opera “Cruzar la Cara de la Luna(To Cross the Face of the Moon).”

“Cruzar la Cara” is a contemporary story set in New York about a multi-generational Mexican American family whose roots in this country were planted when their patriarch, grandfather Laurentino, came to the U.S. via the Bracero Program, which allowed Mexican farm workers to work legally in the U.S. from 1942-1964.

As Laurentino is dying, he looks back on his life and the heartbreak of being separated from his family in Mexico. In the early 1960s, he hired a coyote (smuggler) to bring his wife, Renata, to the U.S., but she died in the desert on her journey there. Not only did Laurentino lose his first wife, he also lost track of their son, Rafael, who was left behind in Michoacan.

In a 2013 interview with the San Diego Union-Tribune, Pepe Martínez said the story of “Cruzar la Cara” was very close to his heart.

“I can say that I lived many years in Los Angeles. I was very young, no wife or kids, but I had my parents and brothers and sisters (on the other side of the border) that I missed and needed. Later I had my own family … but ‘Cruzar la Cara de la Luna’ is completely personal, since I am part of it. The notes that make up the music came out of my heart and mind and now make the music in the first opera with mariachi music. I reiterate my pride and joy,” he said.

“El Milagro” takes place in 1962 at Christmas time in Laurentino’s hometown in the Mexican state of Michoacan. Laurentino and his best friend, Chucho, have been working on farms in Texas but they surprise their wives by returning home for a holiday visit.

Renata wants her husband to stay in Mexico so they can be together, but he feels a responsibility to return to the U.S. so he can provide for his family. Meanwhile, Chucho and his wife, Lupita, have decided to move permanently to America in the new year.

This will be the final Christmas that Renata will celebrate with her son and their extended family in Michoacan before she reluctantly accepts her husband’s request to join him in America in 1963, but — as viewers of “Cruzar la Cara” know — her journey will not have a happy ending.

The human drama in “El Milagro” takes place at the same time Renata, Lupita and the other townspeople are rehearsing for their annual Christmas play, known as a pastorela. It’s the folk story of three shepherds making their journey to Bethlehem to see the baby Jesus. In the Mexican version of the Nativity tale, the shepherds meet temptations and trials along the way at the hands of Satan, but Saint Michael the Archangel arrives to ease their journey.

“El Milagro” is a one-act opera that runs 75 minutes. Librettist Foglia directs the production and James Lowe will conduct the San Diego Symphony. Three mariachi musicians will be part of the onstage cast. It will be sung in Spanish with English and Spanish supertitles projected above the stage.

The operatic singing cast includes Argentinian bass-baritone Federico de Michaelis as Laurentino; Mexican mezzo-soprano Sishel Claverie as Renata; Houston-raised mezzo-soprano Vanessa Alonzo as Lupita; and Venezuelan American tenor Bernardo Bermudez as Chucho. Also featured are Tijuana-born mezzo-soprano Guadalupe Paz, Mexican mezzo-soprano Claudia Chapa and American baritone Héctor Vásquez.

San Diego Opera is only presenting two performances of “El Milagro,” as part of its pared-down 2023-24 season. Martínez said he will not be able to attend the performances due to travel visa issues but he hopes the run is a success and he also helps San Diego Opera expand its audience internationally.

“This is an opera for people of all ages and I think it’s a very good opera for this season and for people of faith,” he said. “It’s especially important for it to be presented in San Diego because there are so many Mexican people there. It’s for the border region because the history of this opera is about immigrants.”

‘El Milagro del Recuerdo (The Miracle of Remembering)’

When: 7:30 p.m. Friday; 2 p.m. Sunday, Dec. 3

Where: San Diego Opera at the San Diego Civic Theatre, 1100 Third Ave., San Diego

Tickets: $13 to $205

Online: sdopera.org

pam.kragen@sduniontribune.com