Before a homicide case can proceed, prosecutors and defense attorneys need to know, officially, how the person died.

Before insurance companies will pay out on a policy when someone passes away, they want that same sort of information. Even for friends and family, autopsies and official rulings can provide answers in an unexpected death.

But for the last two years, the county Medical Examiner’s Office has grappled with more cases than it could quickly handle.

Since 2022, a message at the top of the county Medical Examiner’s Office website has warned visitors they may have to wait up to six months for the office to determine a cause of death and issue a final report.

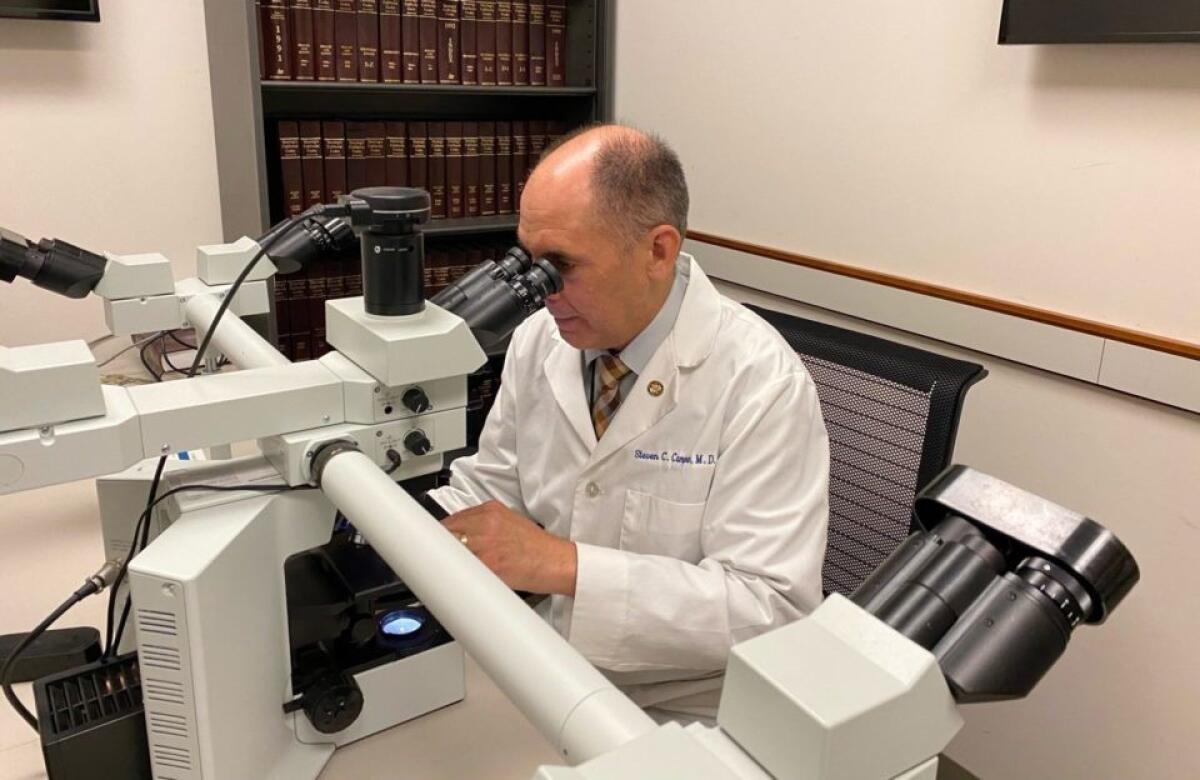

Steven Campbell, San Diego County’s Medical Examiner, peers into a microscope to examine a specimen.

(Courtesy of San Diego County )

The backlog of cases remains, but officials say it is decreasing as the department adds staff. The county also hired a private contractor to catch up on some of the unfinished lab work.

A surge in fatal drug overdoses in recent years — mainly from fentanyl — largely created the workload logjam.

From 2018 to 2022, the number of deaths from drugs or alcohol in San Diego County more than doubled — increasing from 578 to 1,300 — with roughly two-thirds of those due to fentanyl overdoses.

The highly addictive synthetic opioid is illegally sold in various forms including counterfeit pills that look like prescription drugs, and can be fatal in small doses. The Drug Enforcement Agency has called fentanyl the single deadliest drug threat the country has ever faced. More than 110,000 people in the U.S. are believed to have died from drug overdoses in the past 12 months, according to provisional data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In San Diego County, escalating drug deaths fed an overall jump in the Medical Examiner’s caseload — from 3,347 deaths in 2019 to an unprecedented 4,405 cases in 2021, a 30 percent increase.

There were 4,344 deaths investigated by the office in 2022 and 4,161 cases in 2023.

The workload surge hit particularly hard because it came at a time when the Medical Examiner’s Office found itself short staffed.

By May 2022, the county’s Public Defender complained to the Union-Tribune that the delays were gumming up the court system.

“It takes at least six months to get medical examiner reports. Which makes investigating and negotiating homicides almost impossible within that time period,” then-Public Defender Randy Mize said at the time.

At a public hearing that month, a woman waiting to learn details about her brother’s death complained to county supervisors about how painful it was to not have answers for months.

By law, the Medical Examiner’s Office is required to investigate any deaths of a sudden and unexpected nature, as well as any death related to an injury or intoxication.

If a definitive cause of death cannot be determined by an autopsy — something that happens about 30 percent of the time — pathologists will order microscopic, chemical, or toxicological tests to help find the answer.

In cases where toxicology tests and autopsy reports aren’t completed promptly, the office issues death certificates with the cause of death listed as “pending” — a detail that could cause delays if, say, an insurance policy has a clause denying payment if the insured person dies from suicide within a certain time frame.

The past two years, Chief Medical Examiner Steven Campman sought help from the Board of Supervisors, seeking more staff and pay increases to help fill vacant jobs.

The department had 60 budgeted positions in fiscal year 2022 — although at one point, seven of the jobs were vacant. Its budget grew to cover 66 positions the next year and currently stands at 77 positions, county officials said.

File storage at the San Diego County Medical Examiner’s office in Kearny Mesa.

(The San Diego County Medical Examiner)

As of late February, a county spokesperson said 64 of the jobs were filled, with four employees in the process of being hired. The county also hired a toxicology lab manager and increased lab staffing from five to 11 funded positions, nine of which were filled as of late February.

In 2022, in response to complaints about the slow turnaround, county managers turned to an outside laboratory — NMS Labs, hired under a one-year contract not to exceed $98,560 — to get hundreds of toxicology tests completed.

At the peak of the toxicology backlog in January 2023, there were 1,678 cases waiting for results.

By late February, the department was able to complete more than 90 percent of its testing within a standard 90-day window, a county spokesperson said.

Its backlog was down to 471 as of early March, however a spokesperson cautioned that number is constantly changing. The county gets around 240 cases each month that need such testing.

Moving forward, officials hope the in-house toxicology lab becomes more efficient and effective by using grants to purchase new equipment that will allow it to update procedures.

A county spokesperson said the new methods and processes will allow the lab to detect a wider range of drugs using a smaller sample, will increase its testing sensitivity and will improve turnaround times.

A contract with an outside lab, in effect in 2023, will remain in place through June, and is available if needed, the spokesperson said.

Campman turned down requests to be interviewed for this story. In a statement he said he welcomed the improved turnaround times. “We still have work to do but are progressing and I am pleased,” he said. “I am proud of all our staff and am grateful for the support from the County.”

While there remains an ongoing nationwide shortage of pathologists, Campman said the county is attracting candidates and has leveraged contracts where needed.

The county District Attorney’s Office acknowledged prosecutors sometimes have to wait months for autopsy and toxicology reports to be completed, but a spokesperson said the office is able to meet deadlines in homicide cases in the court system.

“We know that like all of us, they have been working tirelessly in the pursuit of justice,” spokesperson Tanya Sierra said in a statement. “Their work is a critical part of homicide cases and the Medical Examiner’s Office has been timely with cases that have a court deadline.”

She added that it is important not only for the justice system, but also to families and loved ones affected, that they are “fully supported and staffed.”