After 11 years of planning work, the Port of San Diego’s future-looking guidebook that dictates what can and cannot be built on thousands of acres in and around San Diego Bay is done — pending sign off from a higher-ranking regulatory agency.

Wednesday, the Board of Port Commissioners voted unanimously to adopt what’s known as the Port Master Plan Update and to certify the plan’s associated environmental impact report. The milestone action clears the way for consideration by the California Coastal Commission, which has the final say on whether the plan becomes the legal blueprint for the bay.

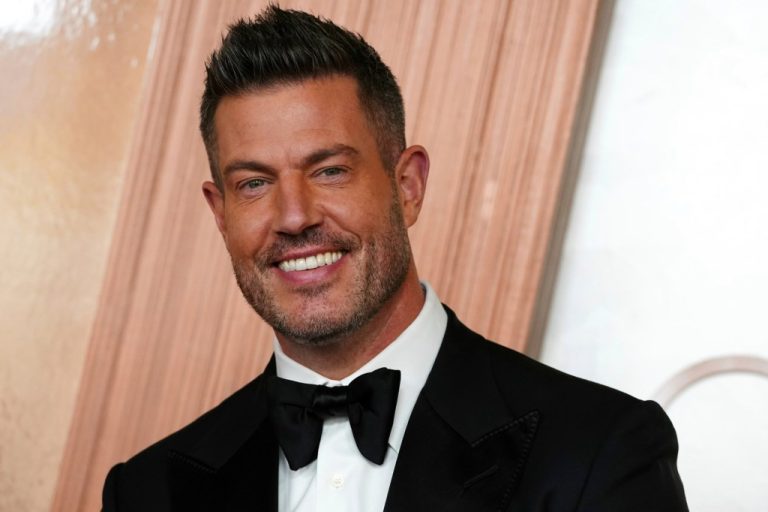

“(The plan) is a major way point for the port, the region and anyone who works, visits or plays in and around San Diego Bay. And it’s the bay that plays the leading role in the (Port Master Plan Update),” Jason Giffen, the port’s vice president of planning and environment, told commissioners ahead of their vote. “We purposely switched the paradigm to think of water first by establishing a water and land use element that guarantees the public realm, increases coastal access, and creatively supports new ways to move people and freight.”

Formed by the state in 1962, the San Diego Unified Port District spans 34 miles of coastline from Shelter Island to Imperial Beach. The land was granted to the agency to hold in trust on behalf of Californians; it includes tidelands in San Diego, National City, Chula Vista, Imperial Beach and Coronado. The agency is a self-funded, non-taxing entity governed by a board of seven commissioners who are appointed by their member cities.

The just-approved document’s planning area covers a limited portion of the special district — or 1,009 land acres and 1,454 water acres — spread across 10 planning districts.

Even still, the plan makes room for 3,910 additional hotel rooms, 340,000 square feet of new retail shops and restaurants, and 20.6 more acres of parks, plazas and open space at buildout in 2050. The increased density extends into the water with space for 75 new anchorages, 485 additional recreational boat slips and 65 more slips for commercial vessels.

As a result, the master plan will result in significant and unavoidable impacts across eight different categories studied in the environmental impact report, including air quality, water quality and transportation.

Alongside creating opportunities for more hotel and retail development, the plan also advances new bay-wide policies meant to further promote public access to the coast, ensure the protection of the region’s natural resources and provide for new ways to navigate around the district.

Additionally, the plan lays the ground work for the overhaul of North Harbor Drive in the North Embarcadero subdistrict into what planners hope will become an iconic waterfront street that prioritizes people over cars.

The plan also envisions new over-the-water experiences, including a 30,000-square-foot “Window to the Bay” pier south of Grape Street and north of Ash Street. And it formalizes the port’s intent to remake the southern, industrial portion of Harbor Drive into a smarter road that better accommodates trucks, passenger vehicles, bikes and pedestrians, while simultaneously becoming a less-polluting neighbor to Barrio Logan.

Commissioners thanked the agency’s staff for wading through the sea of public opinion that has ebbed and flowed with varying intensity since the planning process began in 2013. All appeared to be in agreement that the final product represents the right balance between environmental stewardship, community member desires and the port’s commercial realities.

Not everyone in the audience was in agreement.

“We’re all wearing blue today to show our appreciation for our beautiful bay. And we also want to honor the bay for Californians. And we don’t see that this plan is doing that in the Embarcadero,” said Janet Rogers, who co-chairs the Embarcadero Coalition downtown resident group.

Rogers once again pushed the port to pair back planned hotel development in the Embarcadero planning district and to fold the Seaport San Diego project into the master plan.

In the Embarcadero region, the Port Master Plan Update allows for 850 more hotel rooms than what is allowed under the current plan. The document also ignores the Seaport San Diego project, which would raze Seaport Village and rebuild the surrounding Central Embaracadero with another 2,050 hotel rooms. Instead of incorporating the mega project, the master plan states that the Central Embarcadero will remain in its current condition.

“The South Embarcadero is already wall to wall buildings,” Rogers said. “The whole idea of the Port Master Plan should be to not do that to the rest of the Embarcadero. You can see right now, there are zero hotel rooms in Seaport Village and there’s still some space over on the North Embarcadero side. And there’s lots of room for views. As we go down to the water, we can actually see the water.”

Her comments were echoed by several others who charged the agency with being inconsiderate of its downtown neighbors.

“I would encourage you to be careful that the rear end of the front porch of San Diego is not merely a service delivery eyesore to those who have their front porches facing the rear end of your front porch,” said Rick Gentry, who is the retired CEO of the San Diego Housing Commission and lives in the Grande North tower on Pacific Highway. “We are your neighbors. We deserve consideration.”

Commissioners acknowledged the comments but noted that the downtown waterfront is urban by design. They also reminded people that the allowed number of hotel rooms was previously cut back to appease critics.

“This is a dense, urban environment and that’s the way it is. That’s what’s in the (Downtown Community Plan),” Commissioner Ann Moore said. “When people purchase condos in the area that’s basically what they should anticipate.”

By contrast, the city of San Diego pushed the port to boost building heights and the allowed development intensity in downtown’s waterfront region. Keith Corry with Mayor Todd Gloria’s office and Tait Galloway, an executive in the city’s planning department, said that the port’s standards should match those in the Downtown Community Plan to ensure ample bayfront hotel development and leave land available for housing within the city’s jurisdiction.

“There is a demand for visitor accommodations, if not now certainly more in the future. And if it’s not provided on port land, which can accommodate visitor accommodations, that will occur on other areas within downtown, which could otherwise be accommodated for residential uses,” Galloway said.

Commissioners felt that San Diego’s request for more hotel development buoyed the case for the agency’s approach.

“When I heard the city of San Diego today talk about, ‘We thought it should be more intense. You should go higher.’ … Well, I think that we nailed it,” said Commissioner Frank Urtasun, who chairs the board. “The Embarcadero Coalition did bring up some real legitimate causes … . But we struck a balance and that’s the big thing here that we’ve done.”

With the board’s approval, the Port Master Plan Update will now go before the Coastal Commission. The review process could take as long as a year, said Lesley Nishihira, who is assistant vice president of the port’s planning and environment division.

In the past, the Coastal Commission has identified issues with the plan’s policies around lower-cost hotel rooms, objected to the preservation of four piers with private docks and advocated for the plan to include the Seaport San Diego project. The agency has also taken issue with planning language that exempts some port tenants from providing public access to the shoreline.